Bonjour Marie-Agnes, Janice et Jean-Claude! Hello again from Scotland!

Please let me begin today, Marie-Agnes et Jean-Claude, by recalling that joyful, sunny day in late summer when Margaret and I met you for the first time, at Biarritz on the Atlantic coast. 🙂 From the deserted street on a quiet Sunday morning, you appeared as if by magic at the doorway of Hotel Marbella; and what an unforgettable day we spent together! Although it feels like only yesterday, weeks have now passed – and last Saturday we re-set our clocks and watches to ‘winter’ time.

Janice, Jean-Claude, Marie-Agnes, it’s now a little over a year since we exchanged messages on the distinguished writer and broadcaster, Sir Ludovic Kennedy, who had just died – and who brings us to our tale! (Sir Ludovic died on 18th October, 2009, aged 89. He’d been married for 56 years to the ballerina Moira Shearer, star of the film ‘The Red Shoes,’ who predeceased him.)

“I can’t think of anyone in the media more universally admired,” I remember writing. He was a charismatic and most attractive figure, as one might say in French, ‘un monsieur fort sympathique.’ Throughout his life, he campaigned against injustice in criminal cases. We quoted a sentence or two, I think, from the introductory pages to Ludovic Kennedy’s book, Thirty-six Murders and Two Immoral Earnings (a fascinating book, giving an account of Kennedy’s lifework in exposing injustices).

“The starting-point of my life-long obsession with miscarriages of criminal justice may be said to have been the library of my grandfather’s house in Belgrave Crescent, Edinburgh .. ” (Grandfather was an eminent lawyer.) “Between the ages of about 11 to 15, I used to spend a part of my Christmas holidays at Belgrave Crescent .. ”

Sir Ludovic then described how his favourite meal of the day had been the generous afternoon tea, served in the library at a quarter to five. With the new electric lamps lit, the heavy curtains drawn against the drizzle and gloom outdoors, Helen, the maid, would enter in turn with two enormous trays, laden with toast, scones, oatcakes, shortbread, gingerbread; and silver pots of both Indian and China tea!

After the meal, young Ludovic would mount the step-ladder to the library’s topmost shelves, where were housed the handsome red volumes of Notable British Trials. Perched on its top step, he would sit entranced for hours, reading of Madeleine Smith and Pierre L’Angelier, Dr Crippen or Oscar Slater ..

It was now the early 1930’s, and e v e r y o n e had heard of Oscar Slater, for during the preceding 20 years, scarcely a day had passed without some mention of his name in the newspapers. Slater had finally been released from prison in 1927, after serving more than 18 years for the brutal murder in Glasgow of a lady of 82, a crime of which he was entirely innocent.

Waiting to meet him at the gates of Peterhead Prison was his friend, Rabbi Phillips (Slater was from a Jewish family, born in Germany in 1872). The Rabbi took Slater to his home in Glasgow, and showed him such kindness that he burst into tears. “Even the sight of a tablecloth on the table was wonderful to a man who’d suffered so much,” wrote Jack House (1906-1991) in Square Mile of Murder (W & R Chambers, 1961; etc) – one of the best accounts of the Slater case that I’ve come across. Please try to see it. Prison conditions were extremely harsh in the 1920’s; discipline was strict and enforced, ultimately, by flogging with the birch rod.

Chers Amis, I’m sure you’ll understand that I can tell here only briefly, the story of a case about which so much has been written over the past 100 years. The whole Slater affair began in the winter of 1908, when, just four days before Christmas, a wealthy old Glasgow lady was found horribly beaten in her flat at 15 Queen’s Terrace (part of West Princes Street, close to St George’s Cross).

Miss Marion Gilchrist’s House in Glasgow, on West Princes Street, formerly Queen’s Terrace – © Google 2010

It was said that Miss Marion Gilchrist – 82 years of age, and in rapidly failing health – had inherited from her father a fortune of between 40 and 80 thousand pounds (in today’s terms, a sum of between four and eight m i l l i o n pounds) – and that she had changed her will just a short time previously, in order to disinherit members of her own family with whom she was not on good terms.

Miss Gilchrist lived simply but comfortably, with only her maid, Helen (Nellie) Lambie for company. She kept a large collection of diamond jewellery in the flat, and had become extremely anxious about her personal security. About seven o’clock one Monday evening, just after Nellie had gone out to buy a newspaper, Miss Gilchrist was attacked and beaten to death in her dining-room by an intruder. The murder weapon was a heavy mahogany chair; possibly also a metal auger which the killer had brought into the first-floor flat.

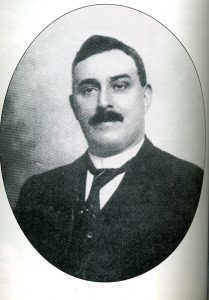

As far as the police were concerned, suspicion fell immediately upon Oscar Slater, a ‘foreign-looking’ man of 36, who had just made plans to sail to the USA; this was portrayed at Slater’s trial as a ‘flight from justice’. (Slater was arrested as the ‘Lusitania’ approached New York harbour, and naively insisted on returning to Scotland to clear his name. If only he could have foreseen the future!)

It’s thought that Slater had already come to the attention of the Glasgow police before the murder, although he’d been in the city for little more than seven weeks. He’d tried to earn a living in New York and in London; here he’d met his female companion, a young French woman by the name of Andree Junio Antoine. Slater and Miss Antoine rented an upstairs flat at 69 St George’s Road, part of a handsome red sandstone property known as ‘Charing Cross Mansions’ – located just 400 yards from the scene of the murder. While Oscar Slater spent his days in gambling clubs, and occasionally dealing in jewellery, Miss Antoine received gentlemen visitors to the flat under the name of ‘Madame Junio.’ Slater himself used several aliases; the plate on the door read: ‘A. Anderson, Dentist’.

By any standard, Slater’s trial at the High Court in Edinburgh was a travesty of justice. The evidence produced against him was very weak, much of it depending upon identification. The Lord Advocate, Alexander Ure, who – unusually – led the prosecution personally, lost no opportunity to blacken the character and reputation of Slater. Even the judge, Lord Guthrie, suggested to the jury that ‘a man of

t h a t type’ – meaning Slater – had no right to rely upon the usual presumption of innocence.

Slater did not speak during his trial; it was thought that his heavy German accent might prejudice the jury against him. After four days of ‘evidence,’ Slater was found guilty as charged, the jury voting by nine to six in favour of convicting him. [Marie-Agnes, Jean-Claude, Janice, you may find it surprising that there is no need for a jury to be unanimous in a Scottish criminal trial (as would be the case in England). A simple majority – even a majority of one – is sufficient to convict the accused.]

To say that Slater was shocked by the verdict would be an understatement. Now his voice was heard: “My Lord, may I say one word? Will you allow me to speak? .. .. I know nothing about the affair. You are convicting an innocent man. .. .. I came over from America .. .. to Scotland, to get a fair judgment. I know nothing about the affair, absolutely nothing. I never heard the name. .. .. I know nothing about it . .. .. I can say no more.” Lord Guthrie made no observation on this statement. He put on the ‘black cap’ and sentenced Oscar Slater to be hanged on Thursday, 27th May. (Executions usually took place within the old Duke Street Prison in Glasgow. The tall perimeter wall of this old jail still stands in High Street, just south of Cathedral Square.) Death by hanging was the mandatory punishment for murder.

Such was the public outcry that Slater’s sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. (Actually, a Royal Pardon had been granted by King Edward, but this fact was kept secret for many years.) Now began Slater’s long incarceration in Peterhead Prison, and the long agitation to have him set free.

Officialdom held tenaciously to the original jury’s verdict, narrow as the majority had been. Even at his appeal in 1928 (before the new Court of Criminal Appeal, and by which time he was at last at liberty) Slater’s conviction was n o t quashed; rather, it was ‘set aside’ because the judge was held to have misdirected the jury. To put it more simply, it was conceded that Oscar Slater had not received a fair trial.

Slater had accepted an offer of six thousand pounds (about 300 thousand pounds, today) by way of compensation for his wrongful conviction and imprisonment. Thinking to make a fresh start, he moved to a new bungalow in the Clyde-coast town of Ayr (which since at least 1910 had had a small Hebrew Congregation).

Here, in St Phillan’s Avenue, he lived quietly, marrying again in 1936, and by all accounts was popular in the town. He and his wife were briefly interned at the start of the Second World War, as they still held German citizenship. Oscar Slater died in 1948, but this brought no end to an affair that had excited controversy for 40 years.

William Roughead (1870-1952) the Scottish solicitor and criminologist, produced the first book on the Slater case in 1910 (The Trial of Oscar Slater.) With his vivid, lively style of writing, Roughead has been considered one of the founders of the modern ‘true crime’ genre. ( Young Ludovic Kennedy probably read the 1925, revised, edition of Roughead’s book in the ‘Notable British Trials’ series.) But, even in 1910, reviews of Roughead’s account of the trial – especially those in the English press – betrayed much feeling that an injustice had been done. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, never an admirer of Slater, leapt to his defence in the Letters pages of The Times.

Conan Doyle, in turn, produced a short book of his own, based on Roughead’s work, intended to have a mass sale and to arouse public opinion in aid of Slater (The Case of Oscar Slater, 1912, Hodder & Stoughton.) For the first time, prominence was given to the idea that the purpose of the attack upon Miss Gilchrist was not the stealing of jewellery, but rather of some important document, such as her will.

In any account of the Slater case, long or short, tribute must be paid to the memory of Detective Lieutenant John Thomson Trench, the heroic and upright Glasgow police officer who, at tremendous cost to himself, did all in his power to help the unjustly condemned German. One of the country’s most brilliant detectives, Trench sought the protection of the Scottish Secretary of the day before sharing information on the case with William Park, a writer and journalist with the Evening Times in Glasgow. But the politician betrayed him ; Trench was sacked in disgrace from the police, with loss of his superannuation – then prosecuted on a trumped-up charge. John Thomson Trench went on to serve with distinction in the First World War, dying in 1919 at the age of 50.

William Park’s book The Truth about Oscar Slater came out in 1927, by which time the pressure to release Slater was becoming irresistible ; he had already served considerably more than the 15 years usually demanded of those sentenced to life imprisonment. About this time, Slater had the idea of appealing directly to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Employed in the prison’s bookbinding workshop, he wrote a message on a scrap of glossy paper, which was then rolled into a tiny ball and hidden under the tongue of a fellow prisoner about to be discharged. This man took the message to Conan Doyle in London . “Please try again. Oscar Slater,” it said simply.

Jean-Claude, Janice, Marie-Agnes, the newest book (that I know) on the Slater case is also the most revealing – please try to see it, especially for the sake of the excellent photographs. (The original hardbound edition has 24 pages of pictures, many from the Scottish Record Office.)

Oscar Slater – The Mystery Solved by Thomas Toughill (Canongate, 1993. ISBN 0862414512)

The following interview, given by Thomas Toughill to Bruce McKain, legal correspondent of The Herald newspaper (Glasgow) on 7th October 1992, gives an overview of the thesis advanced in his book.

Toughill’s conclusions are devastating. If he is correct, the Slater case was no mere miscarriage of justice, but a m o n s t r o u s c o n s p i r a c y, breathtaking in its audacity, that extended to the highest levels of the Scottish legal establishment.

“(Alexander Ure) .. was involved in the investigation into Miss Gilchrist from the very outset .. .. he was involved in the protection of his Charteris friends (the nephews whom Miss Gilchrist wished to disinherit) from the very beginning .. .. it was Ure’s influence .. .. which accounts for the actions of the Procurator Fiscal and the Glasgow police .. .. before and after Slater’s return from America. .. .. It would have been unthinkable to the conspirators that the sons of a professor (and .. nephews of a scion of the Church of Scotland) (that is, the Charteris brothers) would have been publicly involved in a murder case .. .. “

To my mind, had this book appeared 80 years ago, it would, without doubt, have brought down the government of the day – as, I think, the Dreyfus case did in France – and shaken Scottish society to its foundations. Each generation, it seems to me, must learn afresh the lessons of this appalling story.

A Bientot, Marie-Agnes, Jean-Claude et Janice!

Iain.

FURTHER READING:

Reflections on the Oscar Slater Affair

Hello, saw reference to Oscar Slater in a Josephine Tey novel, The Franchise Affair.

I am interested in wrongful conviction and have been researching the Dreyfus Affair as there is a case ongoing here in Ottawa, Canada, wherein a successful Muslim man has been requested for extradition by France for something that occurred thirty years ago in Paris. Evidence is based on one handwriting sample from a hotel registry card and on hearsay which could be the result of “evidence” being tortured from an unidentified person.

The defense believes that the name given, that of Professor Hassan Diab, is mistaken identity.

If Dr. Diab is extradited, he will be charged with the murder of four people killed in a bomb blast outside a Parisian synagogue on Copernic St. in 1980.

The case has been before Judge Maranger at the court house here in Ottawa over December and is expected to be ended by mid-January 2011.

We are hopeful that there will not be a travesty of justice.

Hello, Shannon –

Thank you for your comment, and for your interest in the Scotiana website.

I’m not familiar with the case to which you refer, but it does sound like a difficult one. Unfortunately, extradition treaties seem to be the subject of separate negotiation between each pair of nations, with no common standard. (There is much feeling at present, here in the UK, that our extradition arrangements with the USA are unfair; the Americans can request extradition of British citizens on mere ‘suspicion,’ without showing evidence.)

Surely the first duty of any national government is towards its own citizens? Let us hope, therefore, that the Government of Canada has in place fair extradition arrangements that depend upon sound and compelling evidence; for while an extradition hearing is not a final trial, the procedure of extradition to a foreign country is immensely disruptive to the individual concerned.

(The question of extradition was, ultimately, irrelevant in the case of poor Oscar Slater – who insisted on returning from the US to clear his name, such was his touching faith in Scottish justice!)

I join you in hoping that Dr Diab will be treated fairly.

With best wishes for 2011 from everyone at Scotiana! 🙂

Iain.

i Iain,

Intersting to see your post on Oscar Slater.

I am presenting a piece on the case at the West End Lectures at Glasgow University on 15 March 2011.

The lecturer is Clare Connely of the Law School.

If you have any photos or other material we could use, I’d be very pleased to have it.

You are invited to the lecture in any event.

Just get back to me at the above email.

Regards

Colin

Hello, Colin –

Thank you for your interest in our website, and for your kind invitation to the West End Lecture on Slater. I hope to be able to attend.

I understand that the popular West End Lectures are organised by the Friends of Glasgow West, an amenity group established primarily to preserve and enhance the built environment of the West End of Glasgow Conservation Area.

My own interest in the Slater affair has been heightened by the fact that the flats featuring in the story still survive from 1908/09. As a student in Glasgow, I knew these addresses well.

Although the lovely old Grand Hotel was lost when Charing Cross was redeveloped to accommodate the M8 motorway, it’s fortunate that at least some of the more handsome red sandstone buildings remain. Among them, within Charing Cross Mansions, is the flat that Slater and Miss Antoine briefly rented – at the corner of Woodlands Road, above the furniture showrooms occupied for many years by Messrs Stuart & Stuart.

We’ve many fond memories of Glasgow, and enjoy coming back occasionally.

On behalf of the team at Scotiana, I’d like to send you our kindest regards and our very best wishes for 2011. 🙂

Iain.

Hello Iain,

I came across this article on the murder and the trial only today , 2018, better late than never)). The funny thing was that my daughters were retelling some story on a murder here in Edmonton and mysterious going ons seemingly happening in the place. Not to be outdone I told them about a murder in Glasgow and I worked in the place it happened and that there were many tales of a woman appearing in rooms. I had to google the address to get the names of all involved and found your site . It was a dental lab for quite a few years and I will admit there were certain places in the building where one started to feel uneasy. I do know that the basement was probably the worst but closely followed by a room on the 1st floor. so the plans of the apartment and which room the murder occurred interest me as there is no mention of anything occurring in basement , yet I know a few folk , who stand by the sightings and the unease felt. I wonder if someone hid there to commit the crime or something was stashed and never searched for there. The maids story just does not feel right. So thanks for great writing and kick starting my mind into thinking I am in an Agatha Christie novel. LOL

A particularly interesting piece on the Slater affair re wrongful conviction and equally good to see this being discussed in lecture halls of law schools across the country.

Having a criminal law practice in Edinburgh trying to prevent any wrongful convictions, we’d be delighted to read or hear more on this.

Best wishes, McSporrans, Criminal Defence Lawyers in Edinburgh

Good day, Ladies and Gentlemen – Thank you for your kind comments, and for your interest in our website.

Have you seen our second post on this, “Reflections on the Oscar Slater Affair”? I doubt that there’s any more fascinating and deeply shocking case in all of Scottish criminal history – at times I’ve felt that words were hardly adequate to describe the enormity of what happened.

I’m deeply indebted to Mr Thomas Toughill for unpicking the strands of this tangled web. (I do recommend his original Canongate book, “Oscar Slater – The Mystery Solved”. Excellent photographs.) Mr Toughill is in no doubt that Alexander Ure, the Lord Advocate no less, conceived of a plan, breathtaking in its audacity, to protect his privileged friends (the Charteris brothers) by convicting a man whom he knew to be innocent, so that they might secure with impunity the murder of Miss Gilchrist. As she effectively died intestate, the brothers shared in her estate – which today would be valued in millions of pounds.

The Glasgow police were implicated in the conspiracy at the highest level, as was the Lanarkshire Procurator Fiscal, James Neil Hart. Thomas Toughill details the monstrous perjury committed by Inspector John Pyper of Glasgow police at Slater’s trial.

Is it conceivable that no-one, no highly-placed person in all of Scotland, suspected Ure’s involvement in this outrage? He went on to become a judge (Lord Strathclyde) and a Privy Councillor.

As the awful truth began to dawn, the response was a massive, officially-sanctioned cover-up. Only in 1989 – 80 years after the travesty of Slater’s trial – were the last of the papers released on this uniquely shocking case.

It was a story that politicians feared to tell – yet one that now must never be forgotten.

With all best wishes from the team at Scotiana!

Iain.

OSCAR SLATER’S SHOES

This story I tell,

is of a man locked in a cell

for twenty years for things he didn’t do

While Justice was denied

In a cell eight paces wide

he’d walk up and down, bitter through and through.

Oscar Slater was his name

and they said he was to blame

and yet they knew that this wasn’t true

But he’d been charged and tried,

sentenced to die

Come walk a mile in Oscar Slater’s shoes

————————————————————————

From the Port of New York

He was taken to the dock

charged with Murder and fleeing from the scene

He was Identified

by witnesses who lied

put him in places he had never been

Yet the Truth he never feared

and so he volunteered

To come to Glasgow Innocence to prove

But he was taken straight to jail

no freedom and no bail

Come walk a mile in Oscar Slater’s shoes

————————————————————————

Convicted by majority

by lies and conspiracy

he was sentenced to hang from the noose

yet the police and others knew

that this verdict was not true

They conspired to keep another on the loose

But letters twenty thousand strong

all said that this was wrong

and that Oscar was wrongly accused

A Secret Pardon was produced

his sentence was reduced

to twenty years in Oscar Slater shoes

————————————————————————

So many years were spent

locked up whilst innocent

complaining always that he should be free

News of his case

well it spread throughout the place

people calling for his liberty

Official enquiries turned him down

in favour of the crown

and their blindness, he could not excuse

So he walked his cell at night

determined to fight

eight miles, eight paces

Oscar Slater’s shoes

————————————————————————

Conan Doyle wrote of the shame

of the case that bore his name

saying he was not the man the witness saw

John Trench, he made a plea

got kicked off the CID

fitted up and slandered by the law

But an argument so strong

would surely right this wrong

and eventually his innocence was proved

in 1927 he was released

he stepped out with relief

just glad to walk in Oscar Slater’s Shoes

————————————————————————

Then the judges set him free

on the technicality

that the jury members were misled

No other culprit named

nobody ever blamed

for sending him away to Peterhead

So he did all of that time

for someone else’s crime

No eveidence, just a German Jew

and eight paces he still walked

he marks his days in chalk

come walk a mile in Oscar Slater’s shoes

Who is responsible for Oscar Slater’s Shoes

Just Put yopurself in Oscar Slater’s Shoes

Words and music by Jim McGinley

I am a psychiatrist in the USA (Detroit, Michigan area) and am doing research on Oscar Slater. I am interested in obtaining a recording of the song Oscar Slater’s Shoes.

Thank you

Philip Parker M.D.

Assistant Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, Wayne State University School of Medicine, (Detroit Michigan)

Philip,

whilst I wrote the song a number of years ago there is no recording as yet.

However, I have now made arrangements to make a recording and I will make sure that you are sent a copy.

Regards and best wishes

Jim McGinley

If possible I would like to contact Ian (son of Nancy Stark) grandson of John Thomson Trench who would be a fourth cousin.

Thanks,

Alf Holliday

Hello,

I’m hoping you can help.

I’m wondering if you know of any photographs taken at the Oscar Slater trial in 1909.

I have a photographic collection from that period and I’m trying to authenticate it.

Thanks

Kind Regards

Malc

ps – I also scored a film and a documentary on Conan Doyle for the BBC!

—

Hello, Malcolm –

Thank you for your comment. I’m sorry, I can’t help much, but you may know that Thomas Toughill’s book contains a few Press photos from the trial.

Photography is not permitted today in Scottish courtrooms. Does any reader happen to know when – and for that matter, why – the ban was introduced, for our law courts are, as a rule, open to the public?

Kind regards from the team at Scotiana,

Iain.

I live in Australia and my grandfather, Ebenexer Gilchrist was the nephew of Miss Gilchrist. My Grandfather emigrated from Scotland first to South Africa, then New Zealand finally Australia. My mother told me the story of the murder of Miss Gilchrist and how Oscar Slater was condemned to death and I believed he had been hangedt for a crime he had not committed. As a result of this belief I have opposed capital punishment. I was pleased to read he was released from jail which then makes me ask the question “Who murdered my great, great aunt?” We always believed the motive was burgularly as she was a wealthy woman.

My Great Grandfather was disowned by his family has he disobeyed them and married a servant of the household, Agnes MacGregor. The family set him up in a carpentry business and then claimed his body when he died for burial. I believe my Great Grandmother could not go to the funeral. His sister Marion was the only one who kept in contact with them. I would be very interested in finding out more about the family and the murder

Thank you

claudia Cunningham

Qld, Australia

Hello, Claudia –

Greetings from Scotland! Thank you for your interest in Scotiana – our readers will be intrigued to know that you have a family connection to Miss Marion Gilchrist, the old lady who was so savagely battered to death.

My understanding is that (as reported in the Daily Record and other newspapers of the time) Miss Gilchrist inherited on the death of her father a sum of between £30,000 and £40,000 – at today’s values, between three and four million pounds. Miss Gilchrist lived quite simply, although she had a passion for collecting diamond jewellery and kept many pieces hidden within her flat. On the evening of her murder, only one brooch was taken.

To know more of the murder, I would refer you especially to the two books by Thomas Toughill – ‘Oscar Slater – The Mystery Solved’ (Canongate, 1993) and ‘Oscar Slater, The Immortal Case of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’ (Sutton Publishing, 2006). Mr Toughill writes with the benefit of research that became possible only after the last of the documents concerning the case were released. They had been kept secret for 80 years. One might reasonably surmise that there had been more than a little to hide – ‘no smoke without fire’, we say.

I urge you to read all that you can about the Oscar Slater affair, and to pass the books on to others in your family. Far from being ‘just another murder’ – and a particularly brutal one – it is a case without parallel in all of Scottish criminal history.

(By the way, someone at Dumfries and Galloway Family History Society (dgfhs.org.uk) may well be able to help you with research in SW Scotland.)

Thank you again for your Comment. Please feel free to get in touch with us again.

With kind regards from all of the team,

Iain.

Hi there

I am studying criminology at higher level so i am fairly new to all this. I have been given the fascinating Oscar Slater to study and in a few weeks I need to present my findings to the department. However I am struggling a bit on how I could relate the case to sociological perspectives. Could you offer some guidance on this I would be really grateful if you could, and also if there is any other information in which you feel would impress my fellow students and lecturers I would be thrilled.

Clare

PS Your website is by far the best I looked at 🙂

Hello Clare –

Thank you for your kind comment. Have you read our second Scotiana post on Slater, ‘Reflections on the Oscar Slater Affair’ – in which I offer an explanation of how the social attitudes and prejudices of the Scotland of 1908-09 made it possible for such an outrage to be perpetrated?

‘A social event is a fact,’ (and thus worthy of study) Emile Durkheim, the ‘founding father’ of Sociology had written – but the science was in its infancy in 1908. The modern sociologist (and social psychologist, too, as well as the student of law) would certainly be fascinated to study the events of the Slater case, in the context of the society in which they took place. What an intriguing cast of characters we have – if only the full facts were known beyond dispute!

Let us accept Thomas Toughill’a analysis of the affair – it’s by far the most plausible and credible of any that I’ve come across. [I confess to having only quite recently thoroughly read Mr Toughill’s second Slater book, ‘Oscar Slater: The ‘Immortal’ Case of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’ (Sutton Publishing, 2006. ISBN 0750945737.) Described as a ‘second edition,’ it is for me virtually a new book, for so much additional information has been added, and many parts completely rewritten. The definitive work, surely, on the Slater case.]

We complain of social class divisions today, but how very much deeper these must have been in 1908, when the pay of an unskilled worker was so low that every middle-class family could afford domestic servants. To be rich in such a society was to inhabit a separate world from the vast majority. And Miss Gilchrist was rich, although she did not live extravagantly. She shared the Victorian middle-class obsession with ‘respectability’ – or, should we say, ‘the appearance of respectability’. There was sometimes hypocrisy here, of course; the sort of hypocrisy that allowed ‘respectable’ gentlemen to maintain wives and families, while consorting with pretty Miss Antoine, Slater’s 20-year-old French mistress.

Miss Gilchrist was deliberately killed, although her murder had probably not been planned. But once she lay dead on the hearthrug, what were her family to do, given the bitter divisions between the various branches? In all probability, they sought the help and advice of friends in high places, such men as Alexander Ure, the Attorney General. Thomas Toughill detects the hand of Ure in the Slater case from the earliest days; learning that the rootless German Jew Slater, a man of ‘doubtful’ reputation, lived close by, and had just made plans to leave the country, he must have seemed an ideal candidate to ‘take the blame’ for the Gilchrist murder. (If only Slater had refused to return from the USA. But it was not to be.)

Thomas Toughill shows the close association that existed between such men as Alexander Ure (son of a former Lord Provost of Glasgow, who’d made his fortune in flour-milling) Hart (Procurator Fiscal) Glaister (Forensic Scientist) and Archibald and Francis Charteris, Miss Gilchrist’s nephews. Doctors, lawyers, pillars of the community, it would seem. Solidly middle-class and upper middle-class figures, yet it appears they were all somehow involved in the plan to pin the blame on the innocent Oscar Slater.

How can one assess the strength of the anti-semitism ranged against him? It is not to be dismissed. The composition of criminal juries in 1908 is worth looking at, too, I think, for the rules are now greatly changed.

Oscar Slater died in 1948 at ‘Oslin,’ the little bungalow in Ayr that he shared with his wife, Lina. Not an observant Jew, his simple funeral took place at the Crematorium of the Western Necropolis, Glasgow, on 3 February.

Good luck with your project!

Iain.

Just a word of correction-

Alexander Ure occupied, of course, the position of Lord Advocate, when he personally led the prosecution of Oscar Slater in Edinburgh in 1909.

He’d been brought up in the smart seaside town of Helensburgh, where his family had a palatial home. Wingate Burrell, the violent, half-crazy ‘black sheep’ of the Charteris family, also had an association with the town.

Iain.

hi I am the great granddaughter of the message girl mary barrowman and I am greatly interested in the Oscar slater case and I am desperately looking for photographs of her. I have a couple of faint ones from books.

Hello, Tracy –

Another reader related to one of the people most closely involved in the Oscar Slater case! Thank you for writing to us. I’m sorry we can’t help with photographs of Mary Barrowman – they must be very rare indeed.

Mary – just a girl of 14 in 1908 – was to be the principal witness for the Crown at Slater’s ‘trial’ the following year.

“At the prompting of her mother,” wrote Jack House, “Mary confessed (to the police) that she had been walking along West Princes Street about ten minutes past seven on the night of December 21 (night of the murder) and had seen a man rush from Miss Gilchrist’s close, pause a moment on the steps, then dash west along the street. Mary was under a lamp-post as he rushed past her, and he knocked against her ..”

Mary travelled to New York as a witness when it was eventually decided to start extradition proceedings against Slater. What an adventure that must have been for a young girl, although the winter Atlantic crossing was probably quite uncomfortable! The Scottish police had been monitoring Slater’s movements, but nevertheless allowed him to travel to the USA. Now they wanted him back – or pretended, for the sake of public opinion at home – to want him back. Thomas Toughill argues most persuasively that they made only a weak case, in the hope that their request for Slater’s extradition would be refused.

The awkward, perverse Slater short-circuited the whole process by insisting on returning to Scotland to clear his name! Surely the chances were one in a thousand that he would have done this? Or is it conceivable that, for all his wanderings, he had some emotional attachment to Glasgow, or to Scotland?

I’d like to mention another book on Slater, Tracy. It has much original and detailed background information – although it’s a book that I think must be considered controversial, for the author (alone among writers on the case) discounts any suggestion of an organised conspiracy.

‘The Oscar Slater Murder Story’ (Richard Whittington-Egan, Neil Wilson Publishing, 2001. ISBN 1897784880) We must accord this writer all due respect, I think, for he had a long career as a Fleet Street journalist, and has had a long-standing interest in Slater, meeting his second wife, Lina, on many occasions.

“(From Beuthen, Germany, around 1890) Slater’s restlessness took him to New York, San Francisco, St Louis, Berlin, Hamburg, Paris, Nice, Monte Carlo, Brussels, London, Edinburgh and Glasgow,” Mr Whittington-Egan writes. Slater had come to the notice of the Edinburgh police in 1897 for disorderly conduct, and was first married in Glasgow in 1901 – to an American woman named Mary (or Marie or May) Curtis Pryor – at Shamrock Street Register Office (close to St George’s Cross). A disastrous marriage, for Mary was an alcoholic. Slater was back in Glasgow in 1905, and again, of course, in 1908.

Slater’s insistence on returning to Scotland from the USA obliged the authorities to put him on trial, for they had to maintain the pretence that they believed him to be guilty. If only this troublesome, wretched man had ‘cleared off’ – carrying the suspicion of guilt with him! Probably it was at this point that Alexander Ure – the Lord Advocate, and an immensely busy man, with political as well as legal responsibilities – took the decision to lead personally the prosecution of Slater. Not in order to be more certain of securing Slater’s conviction, as we might surmise, but rather to have the fullest possible influence over the courtroom drama, so as to minimise the harm that Slater might suffer!

In his brilliant analysis, Thomas Toughill argues most convincingly that Ure set himself the immensely difficult task of securing a Not Proven verdict – and in this he almost succeeded. (The 15 men of the jury voted: Guilty, 9; Not Proven, 5; Not Guilty, 1.) “If two more jurymen had resisted the eloquence of Alexander Ure, Slater would have walked free,” wrote William Roughead.

Yes, he would have escaped punishment, but unless a substantial number of jurors had found him Not Guilty, Slater would have carried the stigma of guilt for the rest of his days. This is the true meaning of the unusual Scottish Not Proven verdict – a verdict that would have suited the conspirators’ purpose well enough, while not inflicting punishment on an innocent man.

Of course, Ure had to appear to prosecute the case vigorously, he could hardly do otherwise. “But he went at it too hard,” writes Thomas Toughill. A more discerning jury – a more intellectually able jury – would have looked beyond Ure’s irrelevant character assassination of Slater.

How sad that prejudice won the day!

Tracy, I expect you’ve read quite a bit about the Slater story. It has been one of our most popular posts here at Scotiana.

With kind regards from all the team,

Iain.

http://cgi.ebay.co.uk/ws/eBayISAPI.dll?ViewItem&item=201036631543&ssPageName=STRK:MESE:IT

Thought this might be of interest.

I’ve had these for a while and they need a new home

Kind Regards

Malc

I first heard of the Slater case from William Roughead’s essays. It always seemed to me obvious that the persecution of Slater was not mere police incompetence–it had to be a deliberate conspiracy to let somebody get away with cold-blooded murder. Although it comes too late to help Slater, I’m glad to hear the truth is finally emerging about this astonishing injustice.

I am a GGG nephew of Dr Anthony McCall and Mary Greer McCall (nee Gilchrist) and since discovering the family link to the murder of Marion Gilchrist have become extremely interested in the case, reading the Toughill and Whittington-Egan publications and a lot of the vast information on the internet.

Dr Anthony and Mary lived in Bournemouth and I have read that Marion visited them there, also Elizabeth Charteris lived with them in Conisbrough and when they moved to Bournemouth. I think Mary was fond of her auntie,as she named her daughter born 1891, Elizabeth Marion Gilchrist McCall.

I have a photo of Dr Anthony McCall but not one of Mary so if there are any out there would be very interested to see. My grandfather is still alive and is their G Nephew, unfortunately no information on the case passed down!

Dr Anthony and Mary McCall also had a son, Major Anthony Gilchrist McCall O.B.E, who served in the Lushai Hills and published a book called the ‘Lushai Chrysalis’ in which he mentions his “dear uncle and friend Brigadier-General John Charteris”, so the McCall and Charteris families would seem to have been close.

Hi Iain,

I am sorry I have not been back on sooner since my post about Oscar Slater’s shoes above but for one reason or another I simply have not had the time.

I will get round to recording the song sooner rather than later now as I have the means to do that.

However, I have another tale to tell.

I used to visit Mrs Slater — Lena — in her later years and she was able to tell me many a tale about her life with Oscar, her marriage, their courtship, their life together, the war years and so on. She also revealed some habits and quirks that Oscar picked up during his time in jail and which never left him — such as what he did when thinking things through, how he tinkered with jewellery in his spare time and so on.

There is a real untold story there which I will write up and possibly publish on my own Strandsky Tales and Stories Site or elsewhere. It might be interesting to meet up with others who are interested in the case to discuss various things and share some knowledge.

http://broganrogantrevinoandhogan.wordpress.com/

Late to the party, but I live in Glasgow where ‘see you oscar’ is still in use for ‘see you later’, but few people are aware of the rhyme’s origin. A fascinating and scandalous case.

Didn’t realise the murdered woman was so well connected and so rich.

Strange now to think it was obviously her family or one of that killed her.

And poor Detective Trench, so sad.

Amazing how after all this time Glasgow people still remember the case.

See you, Oscar.

The 90th anniversary of Slater’s release from prison falls on 14 November 2017. Unresolved, this case remains a stain upon the reputation of the Scottish criminal justice system. We speak of the ‘growth’ and ‘development’ of law, yet the law remains a deeply conservative area and the pace of any change can appear inordinately slow. Nevertheless, the monstrous injustices suffered by Slater did lead directly to the establishment in Scotland of a Court of Criminal Appeal.

Labouring in the granite quarries of Peterhead Prison, Slater had been robbed of almost 19 of the best years of his life. When at last he stepped out that Monday afternoon, it was into a modern world, a world that had greatly changed. He knew next to nothing of the Great War in which tens of millions of young men had fallen; and now the newspapers were reporting unrest and instability in Germany which might again lead to conflict. Motor cars were becoming much more common, the first ‘talking’ film had just appeared, BBC radio been established – and Charles Lindbergh had flown non-stop from New York to Paris !

I’d like to pay tribute to Mr Richard Whittington-Egan, who died in September 2016, a writer who studied the Slater case over many years. I recommend his book for the level of interest it holds, mainly on account of the wealth of detail included, yet I find Thomas Toughill’s analysis of the whole affair very much more convincing.

Richard Whittington-Egan writes of the Adams sisters making a sworn statement before a Justice of the Peace at Lanark – to which town they had moved, and where they had a sweet shop – to the effect that they had both witnessed a man descending the drain-pipe at the rear of their flat on the night of the murder, and, equally significantly, that the police had failed to interview them at all, as close neighbours, regarding the horrific crime.

This elementary failure suggests that the police had it in mind, almost from the start of their involvement, to suggest Oscar Slater as a credible suspect. On account of his frequent moving from city to city, and the suspicion that he lived from the fruits of gambling and prostitution, he had been a ‘person of interest’ to the police for some time. Now they may well have known that he had plans to travel again to the USA.

Dr Francis Charteris’ conversation with the senior investigating officer of the police – very soon after the murder – clearly influenced the course of subsequent events. No-one can doubt that the name of Alexander Ure (Lord Advocate) came up, and that Dr Charteris would have let it be known that he and his family were personally close to Ure.

I’ve often speculated that Oscar Slater would be unknown today, if only the Lord Advocate of 1908 had been an East of Scotland man (as might have been more usual), rather than a senior lawyer from the West. But to add to Slater’s misfortune in being both German and Jewish, he now fell among a group of professional men in Glasgow, many of whom were linked by ties of personal intimacy.

Iain.

I was glad to see that Inspector Trench got a mention here – my grandfather told me that he was the only Police Officer who stood up and publicly said that there was insufficient evidence to convict Oscar Slater.

Inspector Trench (according to my Grandfather) lost not only his job but his police pension. He joined the Army, went to war and as a result, lost his life.

I believe he was a brave man, with conviction.