‘Books!’ said Tuppence.

She produced the word rather with the effect of a bad-tempered explosion.

‘What did you say?’ said Tommy.

Tuppence looked across the room at him.

‘I said “books”,’ she said.

‘I see what you mean,’ said Thomas Beresford.

In front of Tuppence were three large packing cases. From each of them various books had been extracted. The larger part of them were still filled with books.

‘It’s incredible,’ said Tuppence.

‘You mean the room they take up?’

‘Yes.’

(Agatha Christie – Postern of Fate 1973)

Last Saturday, as my calendar pointed to the date of November 13th 2010, it occurred to me that it was the 160th birth anniversary of Robert Louis Stevenson, who was born on a wintry and chilly day, at 8 Howard Place, in Edinburgh. To celebrate this event we’ve decided to open on Scotiana a new category dedicated to the great Scottish writer. As I tried to establish the list of my books written by or about Stevenson, I realized how much space his books took on my shelves.

Stevenson has always been one of my favourite writers. My love for this great story-teller began a long time ago when I first read Treasure Island, in an old illustrated French edition, probably an abridged one. Adventure books were supposed to be for boys then, but as I was more attracted by that kind of books than by those generally reserved for girls, it is with great pleasure that I followed the perilous adventures of Jim Hawkins, Dr Livesey and squire Trelawney, on their long journey to find the much coveted treasure in a mysterious island.

SQUIRE TRELAWNEY, Dr. Livesey, and the rest of these gentlemen having asked me to write down the whole particulars about Treasure Island, from the beginning to the end, keeping nothing back but the bearings of the island, and that only because there is still treasure not yet lifted, I take up my pen in the year of grace 17__ and go back to the time when my father kept the Admiral Benbow inn and the brown old seaman with the sabre cut first took up his lodging under our roof.

I remember him as if it were yesterday, as he came plodding to the inn door, his sea-chest following behind him in a hand-barrow—a tall, strong, heavy, nut-brown man, his tarry pigtail falling over the shoulder of his soiled blue coat, his hands ragged and scarred, with black, broken nails, and the sabre cut across one cheek, a dirty, livid white. I remember him looking round the cover and whistling to himself as he did so, and then breaking out in that old sea-song that he sang so often afterwards:

Fifteen men on the dead man’s chest—

Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!

Stevenson’s life was terribly short but it is a long story to tell, full of events and adventures as in his novels. A lot of ink has been spilled over it and I will only recall the main events here.

Robert Lewis Stevenson (he would later change his name of ‘Lewis’ for ‘Louis’) was the only son of Margaret Isabella Balfour (1829–1897) who belonged to an old gentry family and of Thomas Stevenson (1818–1887), son of Robert Stevenson who had become famous all over the world for the building of lighthouses. Lighthouse designing had indeed become a family affair and, had he been born with a more robust constitution, the young Stevenson would perhaps have followed on the steps of his ancestors. It was finally decided that he would study law rather than engineering at the University of Edinburgh, which he did succesfully.

But the young man wanted to become a writer. Leading a bohemian style of life which strongly antagonized his family, he began to write for periodicals. In order to restore his health, which was worsening under the Scottish climate, he decided to look for sunnier skies, and thus began a new life of travel, writing down his experiences in a number of captivating travel books.

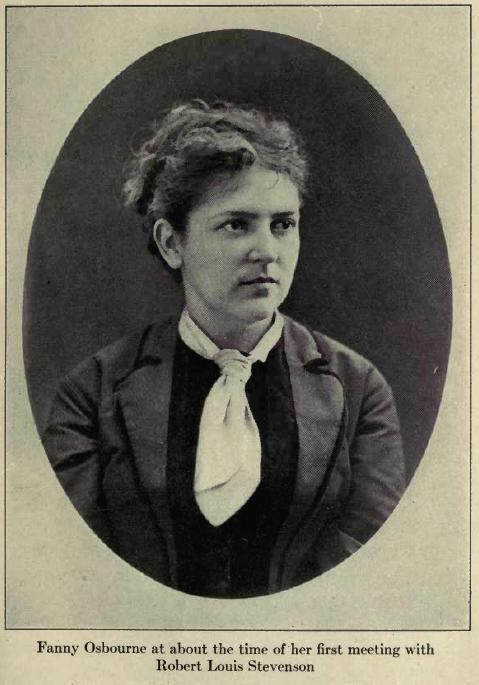

In France, he met Fanny Osbourne, his future wife. After a long and adventurous periple which led him in the New World and the South seas, he finally settled with his wife at Vailima, in Samoa, where he became very popular under the nickname of ‘Tusitala’ which means ‘story-teller’ in the local language… a well-worth reputation. Stevenson has become famous all over the world for his adventure novels, his short stories and tales.

Despite ambiguous feelings , Stevenson certainly did love his native country and, had he lived longer, he would probably have returned to his roots.

‘Stevenson’s love of his native land is understood mainly by means of his absence from it. He is perhaps the most celebrated ‘Scot abroad’ and in this respect he leads a literary pantheon occupied by such figures as George Buchanan, Sir Thomas Urquhart, R B Cunnighame Graham, Alastair Reid and Kenneth White. A book remains to be written on this major but neglected area of Scottish literary history.’ (Tom Hubbard – Stevenson’s Scotland – Introduction)

I was born within the walls of that dear city of Zeus, of which the lightest and (when he chooses) the tenderest singer of my generation sings so well. I was born likewise within the bounds of an earthly city, illustrious for her beauty, her tragic and picturesque associations, and for the credit of some of her brave sons. Writing as I do in a strange quarter of the world, and a late day of my age, I can still behold the profile of her towers and chimneys, and the long trail of her smoke against the sunset; I can still hear the strong strains of martial music that she goes to bed with, ending each day, like an act of an opera, to the notes of bugles; still recall, with a grateful effort of memory, any one of a thousand beautiful and specious circumstances that pleased me, and that must have pleased anyone, in my half-remembered past. It is the beautiful that I thus actively recall; the august airs of the castle on its rock, nocturnal passages of lights and trees, the sudden song of the blackbird in a suburban lane, rosy and dusky winter sunsets, the uninhabited splendours of the early dawn, the building up of the city on a misty day, house above house, spire above spire, until it was received into a sky of softly glowing clouds, and seemed to pass on and upwards, by fresh grades and rises, city beyond city, a new Jerusalem, bodily scaling heaven…

Memory supplies me, unsolicited, with a mass of other material, where there is nothing to call beauty, nothing to attract – often a great deal to disgust. There are trite street corners, commonplace, well-to-do houses, shabby suburban tan-fields, rainy beggarly slums, taken in at a gulp nigh forty years ago, and surviving to-day, complete sensations, concrete, poignant and essential to the genius of the place. From the melancholy of these remembrances I might suppose them to belong to the wild and bitterly unhappy days of my youth. But it is not so; they date, most of them, from early childhood; they were observed as I walked with my nurse, gaping on the universe, and striving vainly to piece together in words my inarticulate but profound impressions. I seem to have been born with a sentiment of something moving in things, of an infinite attraction and horror coupled. (Early Memories – Robert Louis Stevenson)

Robert Louis Stevenson A Child's Garden of Verses London; John Lane - New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1909

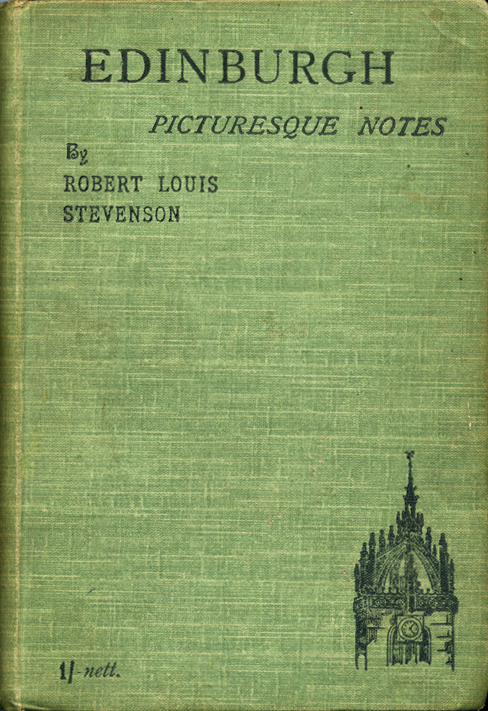

Robert Louis Stevenson Edinburgh Picturesque Notes London Seeley & CO.Ltd. 38, Great Russell Street 1903

The old edition of Treasure Island which had enchanted my childhood has long since disappeared but it is with a child’s enthusiasm that I’ve rediscovered this novel recently, in a more austere and unabridged edition. Maybe I owe to those olden times my love for ancient books and the nice illustrations we often find in them. Indeed, when I happen to fall upon a cheap old edition of a book written by one of my favourite authors, I can’t resist to the temptation to add it to my library, as was the case with the 1903 edition of Stevenson’s Edinburgh Picturesque Notes and the 1909 edition of A Child’s Garden of Verses. The first one is a captivating light and dark picture of Edinburgh and the second one is a marvellous little book of poetry written for children, with many delightful illustrations in it.

A Child’s Garden of Verses is dedicated to his nurse Alison Cunningham. ‘Cummy’, as she was nicknamed, had looked very affectionately after Stevenson, when he was a little boy, all the more since he was very often confined to bed because of recurrent fits of illness. Cummy seemed to possess an extensive repertoire of old stories which she used to tell him, thus contributing to enrich the imagination of the child who already began to invent his own stories …

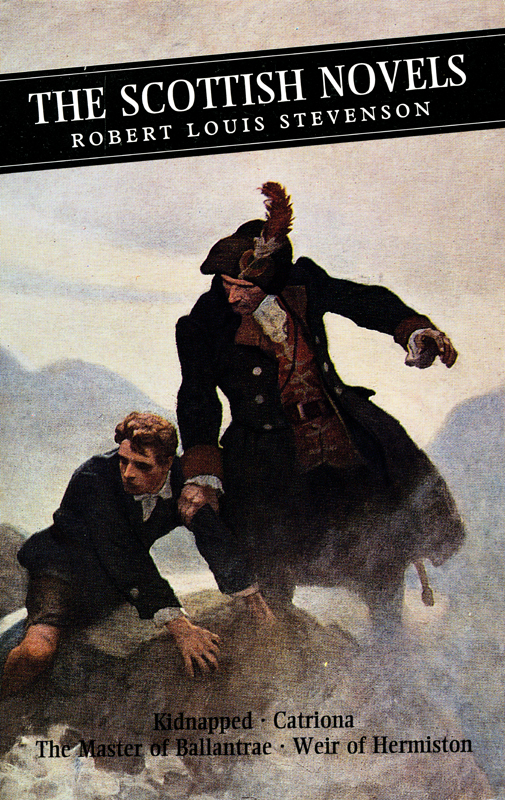

Canongate books has published a number of Scottish classics and among them most of the books written by Stevenson. In 1995, a big volume appeared containing four of his most famous novels:

Kidnapped (1886) subtitled ‘Being memoirs of the adventures of David Balfour in the year 1751. How he was kidnapped and cast away; his sufferings in a desert isle; his journey in the wild Highlands; his acquaintance with Alan Breck Stewart and other notorious Highland jacobites; with all that he suffered at the hands of his uncle Ebenezer Balfour of Shaws, falsely so-called.’

Catriona (1893) which is the sequel of Kidnapped and was published seven years after it which explains the author’s comment in a letter to Charles Baxter: ‘ It is the fate of sequels to disappoint those who have waited for them; and my David, having been left to kick his heels for more than a lustre in the British Linen Company’s office, must expect his late re-appearance to be greeted with hoots, if not with missiles’.

The Master of Ballantrae (1889) was written between Kidnapped and Catriona. In a very interesting introduction to this book, Eric Watson writes: ‘The Master of Ballantrae is a challenging book, and numerous readers have puzzled over its dynamics. On the surface the novel looks like an adventure epic – a marriage of Kidnapped, Treasure Island and Fenimore Cooper’s leatherstocking tales, with something of the later Kipling, perhaps in the mysterious Secundra Dass. And yet earlier readers were puzzled by the book’s final effect, which did not seem to fit the adventure conventions at all (…) With all the apparently familiar adventure trappings of Treasure Island, Kidnapped, and even of Jekyll and Hyde, he has produced a memorable ‘winter tale’ instead: a tale which ends in mere blankness, just as the brothers end, in a wilderness of cold and night.’

Weir of Hermiston is Stevenson’s last and unfinished book.

Below is an extract of Kidnapped in keeping with the illustration of the cover.

Robert Louis Stevenson The Scottish Novels Canongate 2002 Cover: The Torrent in the Valley of Glencoe by N.C. Wyeth

The mist rose and died away, and showed us that country lying as waste as the sea; only the moorfowl and the pewees crying upon it, and far over to the east, a herd of deer, moving like dots. Much of it was red with heather; much of the rest broken up with bogs and hags and peaty pools; some had been burnt black in a heath fire; and in another place there was quite a forest of dead firs, standing like skeletons. A wearier-looking desert man never saw; but at least it was clear of troops, which was our point.

We went down accordingly into the waste, and began to make our toilsome and devious travel towards the eastern verge. There were the tops of mountains all round (you are to remember) from whence we might be spied at any moment; so it behoved us to keep in the hollow parts of the moor, and when these turned aside from our direction to move upon its naked face with infinite care. Sometimes, for half an hour together, we must crawl from one heather bush to another, as hunters do when they are hard upon the deer. It was a clear day again, with a blazing sun; the water in the brandy bottle was soon gone; and altogether, if I had guessed what it would be to crawl half the time upon my belly and to walk much of the rest stooping nearly to the knees, I should certainly have held back from such a killing enterprise.

Toiling and resting and toiling again, we wore away the morning; and about noon lay down in a thick bush of heather to sleep. Alan took the first watch; and it seemed to me I had scarce closed my eyes before I was shaken up to take the second. We had no clock to go by; and Alan stuck a sprig of heath in the ground to serve instead; so that as soon as the shadow of the bush should fall so far to the east, I might know to rouse him. But I was by this time so weary that I could have slept twelve hours at a stretch; I had the taste of sleep in my throat; my joints slept even when my mind was waking; the hot smell of the heather, and the drone of the wild bees, were like possets to me; and every now and again I would give a jump and find I had been dozing.

The last time I woke I seemed to come back from farther away, and thought the sun had taken a great start in the heavens. I looked at the sprig of heath, and at that I could have cried aloud: for I saw I had betrayed my trust. My head was nearly turned with fear and shame; and at what I saw, when I looked out around me on the moor, my heart was like dying in my body. For sure enough, a body of horse-soldiers had come down during my sleep, and were drawing near to us from the south-east, spread out in the shape of a fan and riding their horses to and fro in the deep parts of the heather.

When I waked Alan, he glanced first at the soldiers, then at the mark and the position of the sun, and knitted his brows with a sudden, quick look, both ugly and anxious, which was all the reproach I had of him.

“What are we to do now?” I asked.

“We’ll have to play at being hares,” said he. “Do ye see yon mountain?” pointing to one on the north-eastern sky.

“Ay,” said I.

“Well, then,” says he, “let us strike for that. Its name is Ben Alder. it is a wild, desert mountain full of hills and hollows, and if we can win to it before the morn, we may do yet.”

“But, Alan,” cried I, “that will take us across the very coming of the soldiers!”

“I ken that fine,” said he; “but if we are driven back on Appin, we are two dead men. So now, David man, be brisk!”

(Robert Louis Stevenson – Kidnapped – Chapter 22 ‘The Flight in the Heather: The Moor’)

Edinburgh David Balfour & Alan Breck statues © 2006 Scotiana

While we were reading Kidnapped we learned about the existence, in Edinburgh, of two bronze statues representing David Balfour and Alan Breck, the two heroes of the novel. On our following trip there, we tried to find them. It was not easy and without the indications given to us at the Edinburgh Writers’ Museum and by a nearby security guard, we would probably never have found them. We also learned that the statues had been unveiled by another Scottish heroe whose name is… Sean Connery 😉

http://heritage.scotsman.com/robertlouisstevenson/Sir-Sean-unveils-statue.2562733.jp

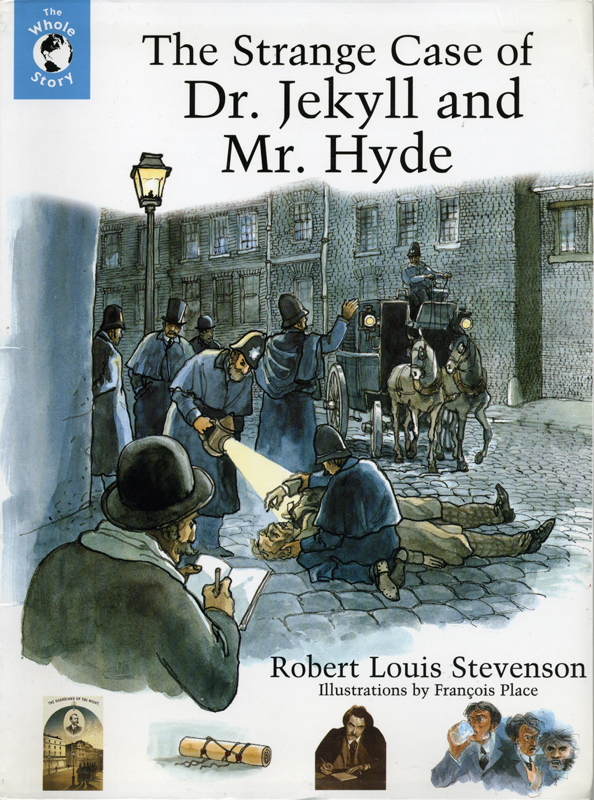

Many of Stevenson’s books contained in my library are still on my reading list but some of them have been read one or several times like, of course, the three most famous ones: Treasure Island, Kidnapped and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

.

Robert Louis Stevenson The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde Viking Illustrations by François Place 1999

I would like to make special mention of Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes (1879). I’d rather say Voyage avec un âne dans les Cévennes since I’ve read it in French. This little book, which was written by Stevenson when he was 29, after one month of solitary walk in the wild countryside of the Cévennes, is a masterpiece of travel writing. There is a number of very interesting and lavishly illustrated books about the Stevenson’s Trail in the Cévennes.

Among these books, I would like to recommend Le chemin des crêtes. This very beautiful book, which contains a lot of nice water colour illustrations, has been written by Kenneth White. We’ve recently introduced this great contemporary Scottish author on Scotiana and we intend to say more about him in our next posts. The Blue Road, one of his most successful books , has been our travelling ‘bible’ on our itinerary towards Labrador, in Quebec. Kenneth White has created the concept of ‘geopoetics’. He is a great traveller and also a great admirer of Stevenson.

Stevenson was a marvellous story-teller and a very prolific writer. He wrote many books, in different genres : poetry, novels, tales, travelling books, essays… I often wonder how he can have managed to write so many of them in so few years and in such a bad state of health.. ‘I wish to die in my boots’, he had said and so he did. He was only 44 years old and still at work on Weir of Hermiston when he died, a book which would remain unfinished and of which he had said ‘It’s so good that it frightens me’. It begins : “In the wild end of a moorland parish, far out of the sight of any house, there stands a cairn among the heather, and a little by east of it, in the going down of the brae-side, a monument with some verses half defaced. It was here that Claverhouse shot with his own hand the Praying Weaver of Balweary, and the chisel of Old Mortality has clinked on that lonely gravestone. Public and domestic history have thus marked with a bloody finger this hollow among the hills; and since the Cameronian gave his life there, two hundred years ago, in a glorious folly, and without comprehension or regret, the silence of the moss has been broken once again by the report of firearms and the cry of the dying.”

As if to say good bye to his native land, Robert Louis Stevenson was writing on these pages when he suddenly died, probably from a brain haemorragia, and so far from Scotland …

Under the wide and starry sky,

Dig the grave and let me lie.

Glad did I live and gladly die,

And I laid me down with a will.

This be the verse you grave for me:

Here he lies where he longed to be;

Home is the sailor, home from the sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.

(Robert Louis Stevenson)

Bonne lecture.

A bientôt.

Mairiuna.

I have an addition of Kidnapped by R.L. Stevenson pub. in 1909 by Macmillon Co. Probably the use was for elemantary schools. It’s in good condition and I would like to know the value of it if I sold this copy.

Hi Donna,

I researched the Internet and more specifically at http://www.abebooks.com in the rare books section, but unfortunately did not find a selling copy that could of given you a guideline of what price you could expect to get if you were to sell the 1909 edition that you own. If ever I do come across some information, I will come back here and update.

All the best,

Janice

i have book title treasure island kidnnaped by robert louis stevenson the regent press, no edition i like to know if this is original or not.thank you

We do not know this edition but maybe our readers can help out. We’ve checked on Abebooks.com, Alibris.com, Amazon.com and other major book sites but will continue to search. Is it an old book? Does it have a jacket? Would be delighted to find it. 🙂

I too have the regent press edition. No jacket, and while the title page reads The Regent Press – New York, on the following page reads printed and bound by JJ Little & Ives. I believe it is published 1908, as the illustration prior to the title page is copyrighted 1908 (by Bigelow & Smith Co)