Bonjour Marie-Agnès, Janice et Jean-Claude! Ca va? – How are you? 🙂

We’d like to tell the story today of the quiet, diffident Scotsman who is generally accepted as the inventor of the bicycle; but first, please let us say how thrilled we were to see the excellent photos you’d taken at Gretna, in the course of three separate visits. (‘Married at Gretna Green!’) Thank you for these, they bring the whole thing to life!

Gretna is easy to get to, for it’s very close to the motorway and also has a railway station. Its strategic location, as the first stopping place for stagecoaches on the Scottish side of the border, gave it enduring fame. The team of four horses that had been supplied at Carlisle, 11 miles to the south, were also changed for fresh ones at the inn at Gretna Green, allowing average speeds of between five and eight miles-per-hour to be maintained, depending upon the terrain. Next day – we hope! – fed and rested, the ‘Carlisle’ horses would have gone back down, drawing the next south-bound coach.

There seems to have been a set distance between ‘change houses’. We know from local history here in Nithsdale, that coach horses working in the valley were changed at the Mill Inn, New Cumnock, at the famous Queensberry Inn, Sanquhar (Whigham’s) and then at Brownhill, Closeburn. These inns – all of which feature in the life of the poet, Burns – are almost precisely 11 miles apart.

Mr Dane Love, the Ayrshire teacher and prolific writer, gives much information about the coaching days in his book,The Auld Inns of Scotland. (Robert Hale, 1997. ISBN 0709059876.) Average speeds attained by the stagecoaches increased dramatically during the second half of the 18th century, mainly due to the improved quality of the roads; by 1800, it took just six hours to cover the 45 miles between Glasgow and Edinburgh.

Speed would always be important, especially for the long-distance traveller. But for all the improvements, stagecoach travel remained hideously expensive. (In 1833, the fare for an ‘inside’ seat on the Highflyer stagecoach between Kelso and Glasgow was 24 shillings – well over £100 today! ‘Outside’ seats could be had for 12 shillings.)

Kirkpatrick Macmillan from Courthill Smithy in the parish of Keir, Dumfriesshire, was invited to be coachman to a rich local man at 17 years of age. He was good at the job; tall and handsome, he cut a fine figure. He excelled at the breaking in of young horses, trying them out on the road to Moniaive where ponies and the occasional stagecoach were the only traffic.

‘O Castelo de Drumlanrig, em 1880’ – Morris’s Seats of Noblemen and Gentlemen (1880) Source Wikipedia

But smithy work was his lifetime’s ambition, the calling of his father and grandfather before him. His parents were delighted when another fine opportunity came his way – an invitation to be apprenticed to the chief blacksmith at nearby Drumlanrig Castle, the seat of the Dukes of Buccleuch. There he learned to forge iron and fashion wood in the best traditions of Scottish craftsmanship. He made friends with another apprentice, John Findlater, and in the evenings they got together in Pate’s father’s smithy.

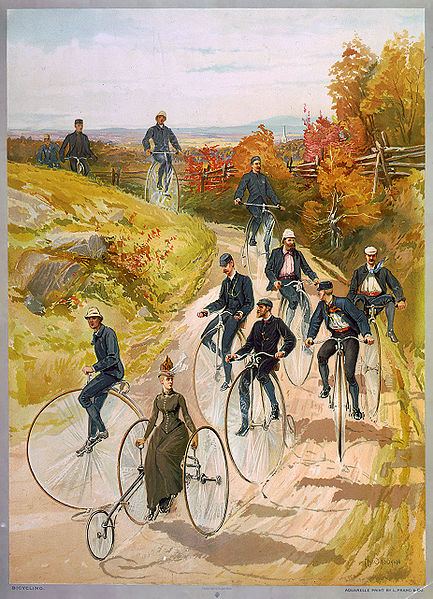

Their first project was to construct their own version of the hobby-horse, a curious walking machine invented by the German Baron von Drais and favoured by gentlemen – and ladies – of the aristocracy. The two lads tried it out on the winding roads of the parish of Keir, attracting much interest from passing stagecoach drivers, in particular a young driver of their own age by the name of Jock Davidson. “Yon’s a hard way to travel ; I doot four wheels is better than twa !” he shouted. Pate was not so sure .. ..

Born in 1813, Kirkpatrick Macmillan was the youngest of the five children of Robert and Mary Macmillan. Two of his brothers had become distinguished members of the teaching profession; John was Classics Master at the High School of Glasgow and George, Second Master of Hutcheson’s Grammar School. The third brother, a clerk in a Glasgow warehouse, and Kirkpatrick, the blacksmith, were seen by the parents to be equally respectable members of society. It was God’s will. Respectability and modesty were very important to the Macmillans of Courthill. They were devout – and strict – Presbyterians.

How, then, did their son Kirkpatrick manage to become ‘the talk of the town’ in Glasgow, appearing in a court of law, attracting gawping crowds in the streets and getting his name all over the newspapers of the day .. ?

Let’s start the story in the Gorbals district of Glasgow, then known as the Barony of the Gorbals.

It was a fine, sunny June afternoon in 1842. A strange rumour was going round the streets. A creature mounted on a pair of wheels was travelling along the road that led to the city from the south side! Word had been spread by breathless passengers dismounting from the Carlisle coach – the apparition was moving at considerable speed and had come many miles already, from as far south, it was said, as the county of Dumfriesshire!

These were superstitious times. Surely this was no human being – a wizard perhaps, or the Auld De’il himself? In roadside villages, terrified mothers had snatched their children indoors and ploughmen had run off across the fields, muttering hasty prayers.

The citizens of the Gorbals were not so easily alarmed. They poured out of their dark, overcrowded tenements to watch the fun, joined by hundreds of Irish immigrants from the Belfast boat, newly docked at the Broomielaw pier.

“It’s around yon corner,” a shout went up, and, sure enough, in a few seconds the infernal machine was in sight. The crowd surged across the street. Swerving, the driver had to mount the pavement. A little girl ran into his path and fell to the ground. She picked herself up, uninjured, but screaming with fright.

The local constabulary were swiftly on the scene. Shouldering their way through the mob, they arrested a broadly-built, good-looking and very embarrassed young man.

It was Kirkpatrick (Pate) Macmillan, who’d earned the nickname ‘Daft Pate’ because he was forever tinkering with his creations and inventions which nobody believed would ever come to anything.

But that day, although he didn’t know it, he had proved himself as the inventor of the world’s first pedal-driven bicycle. Never before had man been able to move on two wheels without putting a foot on the ground. Macmillan had just covered almost 70 miles of rough, pot-holed road on a machine weighing 60 pounds.

Macmillan was horrified. To be involved with the Law went against all his upbringing. He couldn’t believe it was happening to him. To his relief, he was granted bail and went to stay with his eldest brother until his appearance at the Barony Court in the morning. Only his bicycle spent the night locked up.

The magistrates were hard put to it to formulate the wording of this unprecedented charge. Eventually the offence was recorded as: ‘Riding along the pavement on a velocipede to the obstruction of the passage and the danger of the lieges ; and in so doing, having overthrown a child.’ The fine was five shilliings. The publicity the case was given in the Glasgow newspapers was the only recognition the pioneer of the modern bicycle was to receive in his lifetime.

McCall’s first (top) and improved velocipede 1869 based on Macmillan’s model Wikipedia from English Mechanics

At the end of the hearing, the magistrates asked if they could inspect the machine. Proudly Macmillan explained how the pedalling system worked : to the rear axle he had fitted cranks which were connected by rods to the pedals suspended under the upturned handlebars. He showed them the iron-rimmed wheels and the fine carving of a horse’s head decorating the front of the machine. Then he mounted the bicycle and skilfully performed figures-of-eight in the yard of the Barony Court!

In the streets crowds waited for him. He was cheered out of Glasgow. Small boys ran after him until they could run no more. A few older men had a different motive for running alongside. This was an age of inventors and entrepreneurs. Unlike Macmillan’s dismissive countrymen at home , they could see potential here .. ..

At the city boundary, who should he meet but Jock Davidson driving the Carlisle stagecoach! Pate was in exuberant mood and readily agreed that they should race each other the 20 or so miles to Kilmarnock. Soon the stagecoach was left far behind! (In fairness, it should be said that Macmillan was not obliged to stop from time to time, as the coach was, to pick up passengers.)

His bicycle had no lights, so he stayed overnight (as he had done on the way up) with the schoolmaster of Old Cumnock, John Mckinnell, a friend of his brothers from their student days. When the word got around that Pate was safely home, neighbours and friends called at the smithy. They were disappointed he had so little to say about his adventure in faraway Glasgow; the truth was that he felt too ashamed of his escapade to talk about it. He told the whole story to just one person, his friend John Findlater.

Macmillan never sought to register the design of his velocipede, nor did he give any thought to the wider implications of his invention. He continued to work beside his father in the smithy. The city beckoned only once more – he was surprised to receive an offer of employment from the owner of the Vulcan Foundry who had seen him and his vehicle on the road into Glasgow. He was invited to become what we would nowadays call a ‘consultant’ to the firm, at a generous salary.

And so it was that, almost three years after his spectacular first appearance in the city, Macmillan took to the Glasgow road again in the spring of 1845. (Whether he rode on the original bicycle or not, we do not know – he had made more velocipedes by then as gifts for friends, though sadly none survives.) He was introduced to influential people who could have secured for him the recognition he deserved, but he was uneasy in the city and besides, his father wasn’t getting any younger. By the end of the summer he was back home, and for the rest of his life he remained at Courthill.

In 1855, aged 42, Kirkpatrick found a wife, a lady’s maid to the Hunter- Arundell family at the nearby Barjarg Tower. She died 10 years later at the age of 32. There were six children of whom, sadly, only two reached adulthood ; a daughter who became a teacher and a son, a policeman, who settled in Liverpool.

After the death of his father Kirkpatrick Macmillan was in sole charge of the Courthill smithy. He was a well respected member of the community – in emergencies he acted as unofficial dentist and even offered veterinary services. At weddings he entertained the guests with his fiddle playing and a repertoire of whistled tunes as extensive as any of the local shepherds’.

In later life he turned his hand to designing and making agricultural implements and it is said some were bought by Mr Gladstone who wrote a complimentary letter. As the years passed he lost interest in the velocipede, but others did not. One Thomas McColl, who had run alongside when young Pate was passing through Kilmarnock, was selling copies of the Macmillan model from his joiner’s shop at £7 each, a tidy sum then.

Gavin Delzell, a wheelwright from Lesmahagow, sold so many copies that for the next 50 years he was widely believed to be the inventor of the pedal-driven bicycle. In the 1890’s a relative of Macmillan undertook extensive research and received a gracious letter from Gavin Delzell’s son, acknowledging Macmillan as the true inventor.

Kirkpatrick Macmillan died in 1878 at the age of 65. Below his name on the family tombstone in the old kirkyard at Keir Mill are inscribed the words :

INVENTOR OF THE BICYCLE

We hope, dear friends, you have enjoyed reading our story!

On your next visit, perhaps you will see the Scottish Museum of Cycling at Drumlanrig Castle where there is a replica of the Macmillan bicycle. A cycle path – the K M Trail – has been created between Dumfries and Drumlanrig. It passes the Courthill smithy where a plaque bears the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson:

HE BUILDED BETTER THAN HE KNEW.

Courthill Smithy, Kirkpatrick Macmillan plaque -Photo: © Kevin 76’s Flicker on Flickr

A bientôt!

Margaret, Iain.

My late father (Len Thomson) opened an event at Drumlanrig Castle and Courthill Smithy many years ago at the invitation of the, Then, Duke of Buccleuch.

Len Thomson having been traced as a direct living descendant of Kirkpatrick Macmillan.

Mad Pate must have been a descendant of mine so off I go to buy a Penny Farthing.

Well done K.M.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-south-scotland-64963963

It is hoped that a new long-distance cycling route will be inaugurated this summer,

named in honour of Kirkpatrick Macmillan (1812-1878). The ‘Kirkpatrick C2C, South of Scotland’s Coast to Coast’ will stretch for 250 miles, from Stranraer to Eyemouth, and is intended for experienced road-cyclists. (Scotland is a small country, but it’s not tiny!)

Iain.

This year’s Kirkpatrick Macmillan (KM) Rally – 24-27 May 2024 – is planned to be a family affair, and will be based around the pretty village of Penpont, Dumfriesshire (which of course is very close to Keir Mill).

There’s a camping field right in the heart of the village, with showers and toilets on site. To book a camping place or get a list of all the local accommodation providers, please get in touch with the Event Manager, Senga Greenwood, by Email: info.kptdt@gmail.com

Senga’s organisation is the Kirkpatrick Macmillan Trail Development Trust.

Iain.