Bonjour! Hello again Janice, Marie-Agnès and Jean-Claude! 🙂

Our tenth “Letter from Scotland” already!

We often look again at the series of articles you posted last year on the Auld Alliance, especially the description of your visit to the magical Stuart castle, the Château de la Verrerie. (Close to Aubigny-sur-Nère, an Enchanted Stuart Castle : ‘Le Château de la Verrerie’). What an astonishingly beautiful place this is! We never tire of seeing that lovely photo of the Château reflected in the lake, or the picture of the impressive yet charming gatehouse under those noble trees ..

How many people, we wonder, realise that the Auld Alliance goes back more than 700 years? It’s the oldest international treaty in the western world; «La Plus Vieille Alliance du Monde» General de Gaulle called it, when he spoke in Edinburgh during the war. And how many realise that it was actually a triple alliance, between France, Scotland and Norway – signed in Paris in 1295, then ratified in Dunfermline and in Bergen the following year?

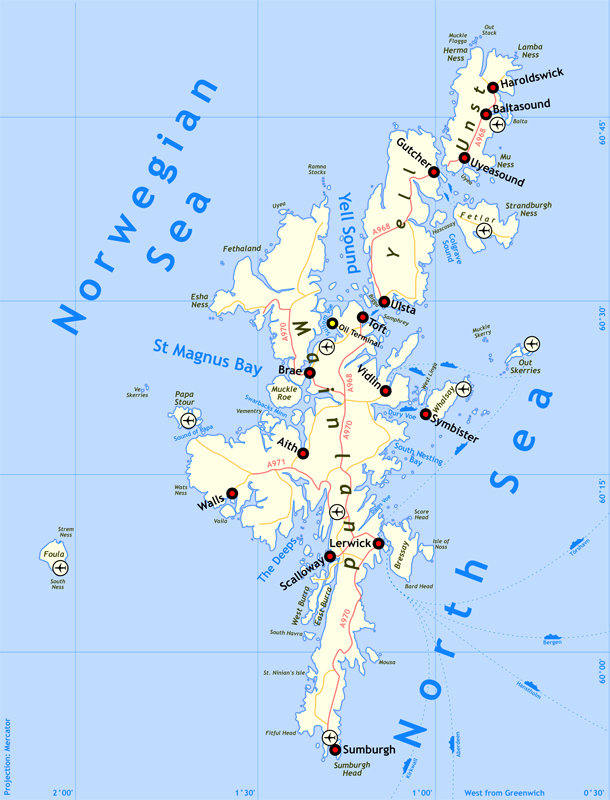

For centuries there have been strong links between Scotland – and especially the Shetland islands in the far north – and Norway (Lerwick, the Shetland capital, is equidistant between Bergen and Aberdeen.) For almost 300 years, until the late 15thC, all of the Orkney and Shetland islands were actually under Norwegian rule.

The ‘Shetland Bus’ (1940-45) of the Second World War was much more than a transport and logistics operation linking Shetland with occupied Norway; originally headquartered at remote Lunna House, intelligence, commando and all manner of secret operations were undertaken.

(See David A Howarth’s famous book, The Shetland Bus. Originally published in 1951, and subtitled ‘The Story of the Special Norwegian Naval Unit based in Shetland’, the book has run to many editions. We seem to recall seeing the grave of Mr Howarth in the burying-ground near the tiny, ruined Lunna Church – which, interestingly, has a leper’s hole cut into its wall.)

The Lunna peninsula is well to the north of the Shetland mainland, but our tale today – of Miss Mouat’s unplanned visit to Norway, that almost cost her her life – begins in the far south, close to where Sumburgh Airport now stands.

————————————————————————-

Scatness Big Waves | Photo Mike McFarlane | McF-photo on Flickr (http://www.flickr.com/photos/mcf_photo/)

A northerly wind was already whipping up the waves around the waiting Columbine when Miss Betty Mouat, the only passenger on its imminent sailing to Lerwick, arrived at Grutness pier from her home in the hamlet of Scatness near the high cliffs of Sumburgh Head. It was a Saturday morning in January and bitterly cold. Miss Mouat was 61 years of age.

The year was 1886 and it was not unusual then for the crofters of Scatness – women as well as men – to walk the 24 miles to Lerwick to sell their work to the prosperous wool merchants. Betty Mouat had a congenital lameness which had worsened these last 15 years, and was reluctantly making the journey along the coast in this small sailing boat. Following a slight stroke, she was anxious about her health and hoped to find a doctor in Lerwick who would see her. She had always been a poor sailor and did not expect to have much appetite for the two halfpenny biscuits and the jar of milk she had packed. The skipper of the Columbine warned her that the voyage was likely to be rough, but she had been preparing herself for the trip for some time now and wanted to get it over and done with. The prospect of an uncomfortable few hours did not worry her unduly. She was not in the habit of expecting life to be easy.

Betty Mouat was well used to poverty and hardship. Six months after her birth her father, Thomas Mouat, had found work for a season at the whaling to augment his meagre income from crofting. His ship set sail for Greenland and somewhere in the Arctic disappeared. Her mother re-married and moved to her new husband’s crofthouse at Scatness.

Betty Mouat – Source: Shetlopedia ©Shetland Museum and Archives (http://photos.shetland-museum.org.uk) Photo_00106.jpg

Betty never married. After her mother died she stayed on with her half-brother, James Hay, and his family, helping on the land and knitting, patiently resigning herself to the life of drudgery that was a woman’s lot in Shetland in those days. Her solace was religion.

The sailing boat Columbine-Source: Shetlopedia ©Shetland Museum and Archives (http://photos.shetland-museum.org.uk) Photo_AI00006.jpg

James Hay saw her off in the Columbine, carrying aboard for her a great bundle of knitting to sell, some of her own and 40 shawls she was taking as an obligement to neighbours. James promised to come down to meet the boat when it returned that evening. He was not to know that it would be seven weeks before he saw his sister again, nor that Betty Mouat from Shetland would return as the most famous woman of the day with a letter from Queen Victoria waiting for her on the mantelpiece.

Bidding her brother not to wait any longer in the bitter cold, she went below with the milk, biscuits and a pair of Fair Isle gloves she would finish knitting to pass the time. She listened to the sounds of the three-man crew casting the boat off from the pier. As the Columbine turned towards the open sea, it began to roll heavily and she had a feeling that this might indeed be the beginning of a rough passage, rougher than any she had experienced.

Feeling suddenly unwell, she sat down at the foot of the ladder that led from the deck to the cabin. From above, the sound of the Captain’s voice came clearly through the hatch. He was shouting, giving a string of urgent orders she did not understand, something about a broken main-sheet .. .. Then there were footsteps running on deck, loud creaking and banging noises, what she thought must be the launching of the small boat ; and all the time the Columbine was rolling and shuddering and she felt so ill she could hardly lift her head.

Had she fallen asleep in that sitting position? All was now quiet. Not a word was being exchanged above. Several times she tried to climb the ladder to have a look along the deck, but each time a violent movement of the boat threw her back in a different direction. Finally she accepted that there was no need. She was alone on the Columbine.

For most of what was to be a voyage of eight nights and nine days Betty Mouat stayed alive by keeping continuous hold of a rope hanging from the roof of the cabin. She held on first with one hand then with the other until both were raw and blistered. Had she let go, she would have been dashed to pieces against the walls. She believed it to be Monday evening when she succeeded in making loops with twine to ease the strain on her hands. But she had to stay alert to avoid being struck by the furniture being thrown around the cabin by the uncontrolled movement of the boat. From the beginning to the end of the nine-day voyage she could not lie down. She managed to reach the Captain’s jacket on the back of a chair and wore it over her shawl which was damp with sea spray. In a pocket she found his watch, still ticking.

The ship’s provisions were in the forecastle but the companion ladder had fallen down and it was too heavy for her to lift back into place. The two thick Shetland biscuits and the milk were all the food she had. She rationed herself to a sip of milk and half a biscuit a day.

On Wednesday she took the last of the biscuits and the milk. She had lost all hope of survival, but she was calm for she believed that her God would be merciful when it came to the end.

In the dark hours of that night Betty Mouat slept fitfully, still hanging from the ropes. The next day, for the first time on her voyage, she was awakened by the brightness of the morning sun. The boat still plunged and reared, but the rhythm was more gentle. After much manoeuvering she succeeded in wedging a box under the hatchway and standing on it she saw some land, low hills with snow-covered mountains behind. But a change in the direction of the wind was carrying the Columbine, stern first, farther and farther out to sea. All day she struggled to keep a lone watch for passing ships. On Friday the storm blew up again with all its earlier fury. On Saturday it was getting dark when Betty Mouat realised with a mixture of horror and hope that the little vessel had struck rocks. The Columbine was thrown by the force of the gale against one jagged rock after another, its timbers grinding and creaking and threatening to split. All night the boat was tossed from rock to rock as Miss Mouat held on grimly. Dawn was breaking when abruptly all movement of the boat ceased. It had come to rest lying on its side in shallow water off Lepsoy, a small island on the west coast of Norway surrounded by dangerous reefs.

Small boys watching ran for help and soon a crowd had gathered. The only way Miss Mouat could be brought to land was for her to swing hand over hand along a rope rigged up by fishermen. In her desperately weak condition she had to muster, she said afterwards, almost as much will-power to complete these last few yards as she had needed for all the lonely miles she had sailed since she left home.

By a miracle she reached the outstretched hands and they carried her to the nearest village, Ronstad. For three days she lay in bed, fevered and still hardly sleeping, cared for devotedly by fisherfolk whose language she could not understand. Then an Englishman was found living locally – a manufacturer of cod liver oil – and he was able to fill in the details of what had been guessed of the castaway’s story.

In Shetland waters the search for Betty Mouat had been abandoned as hopeless, although every effort had been made to find her in the first few days. Two men from the Columbine had came ashore in the lifeboat with the news that their Captain had drowned and the boat was missing with Miss Mouat aboard. They told the story of how it had happened – the main boom of the smack had broken free, and as they tried to repair it the captain and the mate were flung overboard by heavy seas. The mate managed to haul himself back aboard but the captain was still in the water and fast being swept away. The third crewman helped the mate to launch the lifeboat but the captain had disappeared beneath the waves. As they turned to go back to the Columbine, they were aghast to see her sailing away, powered by the strong wind, at a speed they could not possibly match.

Mr John Bruce of Sandlodge, the laird and the owner of the Columbine, had lost no time in organising a search for Miss Mouat. It was clear to him that only a large vessel could go to the rescue. To launch another small boat on such a night was only to invite more loss of life. All the Shetland sixerns had been beached for the winter – it would be the work of several days to rig the sails again and prepare ballast. The steamer St Clair was just leaving the Orkney Islands. The Earl of Zetland, which served the outlying isles of Shetland, was away for repairs in Aberdeen. A steam-freighter known to be in Shetland waters, the Gipsy, was chartered by Mr Bruce but returned without a sighting after a search covering two hundred miles. The St Clair and then the ‘Earl’ as it was called, searched on their return, but without success. When the Earl came back to port on Monday evening with no news, the search was abandoned.

Not long after the visit of the Englishman, Betty Mouat’s story was front page news in the world’s press. In British newspapers, Miss Mouat’s voyage was given as much coverage as the political sensation of the day, Mr Gladstone’s proposal to give Home Rule to Ireland.

A free passage on a Norwegian ship from Aalesund to Hull was arranged for Miss Mouat, then she boarded a train for the first time in her life. As the train was coming to a halt in Edinburgh she was astonished to see that well-wishers filled the long platform, and hundreds more waited for her as she was driven by horse and carriage up the famous steep road out of the station to Princes Street.

A Shetland family living in Edinburgh had been found for her, as she had requested, a Mr and Mrs Jamieson who welcomed her to their home in Hermitage Gardens. For the duration of her three-week stay in the city the house became a place of pilgrimage for ladies of fashion. Elegant carriages were lined up in the street as well-to-do women from some of the best families in Edinburgh waited their turn to be received by Betty Mouat. They came with gifts and begged for a strand of hair from her head as a keepsake. They questioned her about her ordeal in their Edinburgh accents which she hardly understood, but she did her best to satisfy their kindly curiosity.

Betty Mouat was offered large sums of money to go on exhibition at various venues including the London Aquarium, but she found the idea distasteful. She longed to get back to her croft and the only way of life she had ever known.

As it became known that Betty Mouat was travelling to Shetland on the St Clair, crowds of well-wishers gathered at Leith and then at Aberdeen. A huge welcome was organised for her in Lerwick, but she had become used to crowds by this time and these were her own folk. She stayed in town for three more days with a niece, then she was back home to Scatness. She never left the croft again. The years passed, as uneventful as they had been before her momentous voyage. Now and again tourists would knock at her door and she would give them tea and tell her story simply and with unfailing courtesy. Otherwise she got on with her spinning, her knitting and working the land. At the age of 93 she died peacefully in her bed. It was the 32nd anniversary of her last night on the Columbine.

Columbinebukta | Source: Shetlopedia ©Shetland Museum and Archives (http://photos.shetland-museum.org.uk) Photo_P00499.jpg

The bay in Norway where the Columbine came ashore is now known as Columbinebukta (Columbine Bay). In the centenary year the Lepsoy local history society erected a brass plaque telling the story of the voyage in Norwegian and in English, with a list of local men involved in the rescue of Miss Mouat. (These men received silver medals from Queen Victoria and a share of the £10 reward offered by Mr Bruce of Sandlodge.) The memorial was unveiled on 17th May 1986 by TMY Manson, editor of The Shetland News, author and scholar.

Betty Mouat’s Memorial at Dunrossness Churchyard | Source: Shetlopedia.com

A memorial stone has been erected at Betty Mouat’s grave in Dunrossness churchyard near Scatness.

The croft-house where she lived has been restored as

simple self-catering accommodation, one of nine Shetland Camping Bods. (Another Bod is the former home of Hugh McDiarmid, the poet, who lived on the Shetland isle of Whalsay for nine years.)

A few yards from Betty Mouat’s home, the site of an important broch was found in the late 1970s during the construction of a new road to the airport. Starting in 1995, eleven years of excavation by archaeologists from Bradford University assisted by local volunteers uncovered Old Scatness Broch and an iron age village. Today in the summer months costumed guides show visitors around and local craftspeople demonstrate ancient skills at the Visitor Centre.

A fascinating story, don’t you think?

A bientôt, et bonne lecture!

Margaret, Iain.

James Jamieson of Columbine was the brother of my Great Grandmother.

My Grandfather was named Robert Mouat Fothergil

I have sailed with friends out to Saint Kilda etc. Now 82!

Michael Jones, Ullswater.

Thank you for your interesting comment, Mr Jones. You must be proud to know that one of your ancestors was part of Shetland’s illustrious seafaring tradition. Those old sailors – many in open boats – were exceptionally brave men; James Jamieson, master of the Columbine, was just 36 when he was swept to his death in the storm.

Well done for having reached far-off St. Kilda! Few people achieve this. Were you able to step ashore – were there any traces of a pier?

With kind regards from the team at Scotiana,

Margaret.

My great great grandfather was one of two or three boys/men awarded a medal from the king of Norway for saving her at Lepsøy, Norway. His name was Knud Knudsen Veblungsnes.

I am very interested to know that you are a direct descendant of one of the brave men who rescued Betty Mouat when her boat beached on the east coast of Norway. The name of Knud Knudsen Veblungsnes is inscribed on the memorial unveiled in the centenary year of Miss Mouat’s voyage by the Shetland scholar,the late Dr.T.M.Y.Manson of whom I have personal memories. The rescuers also received silver medals from Queen Victoria and a share in the reward of £10 offered by the local laird, Bruce of Sandlodge,who owned the Columbine.

Just one of the links between Norway and Scotland – especially between Shetland and Norway. Thenk you for your interesting comment.

Kind regards, Margaret.

Regarding David A. Howarth (1912-1991), an excellent display on the Shetland Bus at the new Scalloway Museum makes it clear that although a memorial to Commander Howarth stands close to Lunna Churchyard, there is no grave, for his ashes were scattered on the waters of the Bay. In fine weather, it’s a most beautiful and peaceful spot, and is overlooked by Lunna House, first base of the clandestine operations.

Iain.

Dear Friends,

Be quite certain that the Lunna Kirk is FAR FROM RUINOUS, but beautifully kept and well-looked-after. There are services of worship held, from time to time, but as I live in the island of Unst, I cannot tell you WHEN…….

But this kirk, with its leper-squint, Laird’s Loft and Norwegian graves, is well-worth a visit.

Lis N or Booth

Hello Elisabeth,

I’m happy to confirm that Lunna Kirk is in very fine condition; it certainly appeared very well cared-for when we visited in Spring 2015. I can’t think how I came to make such a careless mistake.

It’s quite remarkable, surely, to find a little church today – in such a remote location, yet clearly so well maintained – at a time when so many others are closing or falling into disuse? Perhaps someone will be kind enough to tell us something of the history of Lunna Kirk, as well as its more modern story?

Thank you for writing to us!

Kind regards from the team at Scotiana,

Iain.