Orkney road on a rainy autumn day © 2012 Scotiana

Hi everybody,

Hi Janice 😉 Many thanks for writing so interesting and funny pages… I’m always looking forward to reading them. What unforgettable moments you’re evoking… I would like so much to be in Scotland again!

We were in Orkney last September for a 4-day trip. The MV Hamnavoe landed in Stromness on Thursday 13 just before noon. The weather was awful and we had still no idea where we were going to sleep in the night. For a moment however we forgot all that, listening to a group of musicians who were playing traditional tunes inside the building of the ferry terminus. We had stayed there for a long moment, enjoying the magic of this unexpected concert, when we realized it was high time to do something if we didn’t want to have to pitch our tent under pouring rain and in a drenched soil. The gentleman who kindly welcomed us at the tourist office was not very optimistic about our chances to find the kind of accommodation we were looking for in the area but he gave us a list of places where we could try our luck. We’d better hurry for night falls early in the North in September. We finally were very lucky to find a nice and very cosy cottage to rent in Kirkwall. We’ll tell you more soon about the place and more especially about its very friendly owners. They well deserve a whole page as you will see 🙂

As the weather did not encourage us to stroll along the streets of Kirkwall we decided, before settling down in our new home and after sharing a good cup of tea at St Magnus Cafe (and of course its choice of delicious Scottish cakes) to visit the cathedral and the Orkney Museum. This very interesting museum is situated on the other side of the road, just in front of the cathedral. Janice has already written a very interesting post about the HMS Royal Oak hologram which you can see there and we’ll soon make you discover some of the other treasures we’ve discovered in this museum.

Luminous clouds above St Magnus © 2012 Scotiana

If you go to Orkney, don’t miss a visit to St Magnus Cathedral.

It’s one of the greatest landmarks of the Orkney Islands. This beautiful white and pink sandstone building, standing in the heart of Kirkwall, shelters treasures and it has more than one story to tell and many a mystery to unveil…

St Magnus Cathedral – Rognvald sculpture © 2012 Scotiana

Founded in 1137 by the Viking Earl Rognvald, in memory of his uncle, St Magnus Cathedral dominates Kirkwall, the capital city of Orkney. It has survived the ravages of time as well as political and religious crises which are often responsible for the destruction many architectural gems. The very name of Kirkwall comes from ‘Kirkjuvagr’ (Church Bay), a Norse name which was later corrupted to ‘Kirkvoe’, ‘Kirkwaa’ and ‘Kirkwall’ but the origin of the name dates back to a former church dedicated to Saint Olaf whose statue you can see in the cathedral.

As its name indicates St Magnus cathedral is dedicated to St Magnus, Orkney’s much venerated patron saint. A very interesting annual 6-day arts festival wears the name of the patron saint.

St Magnus Cathedral – The Nave © 2012 Scotiana

The ‘Light in the North”, as the cathedral has often been called, is Britain’s most northerly cathedral and the result of different architectural styles: romanesque, transitional and gothic. The first impression when you enter it is of a massive architecture mainly due to its big round pillars which look like those of Dunfermline Church Abbey. A very interesting thesis about the history of St Magnus Cathedral and entitled Written in Stone was published in 2011 by Sindre Vik, a student from the University of Oslo.

St Magnus story is recorded in Orkneyinga Saga. The text on the back cover of the Hogarth Edition gives a good idea of the interest of the book. It reads:

‘This is a new translation of the only Norse Saga concerned with what is now part of the British Isles. It tells the story of the Earldom established by the King of Norway in the Northern Scottish islands in the ninth century. After a brief introduction, set in the remote world of legend and myth, it describes the Norse conquest of the Isles and relates the subsequent history of the Earldom of Orkney. It is for a period of three and a half centuries not only the main authority for the history of Northern Scotland, but an important document of the great period of Viking expansion. For the people of Orkney and Shetland Orkneying Saga has a special significance. It might be called their secular scripture, inviting them to recognise themselves as the inheritors and custodians of a dual culture, both Norse and Scottish.

In the Viking period Orkney and Shetland were a crossroads where Celtic, Scottish and Scandinavian cultures met. Many of the Earls were striking personalities. The first was the father of Hrolf, the conqueror of Normandy. Several, including Sigurd, who was killed in Ireland at the battle of Clontarf, travelled widely to plunder and do battle. Two were Saints: Magnus the Martyr, still revered in Orkney, and Rognvald, who built the cathedral dedicated to St. Magnus and visited Jerusalem on pilgrimage.

Orkneyinga Saga is also a most attractive and highly personal work of literature which often quotes Skaldic songs, the original material of all sagas. It has influenced the work of several Scottish writers including Eric Linklater and George Mackay Brown.’

The book cover of the Penguin edition of Orkneyinga Saga is illustrated with a photo of one of the famous walrus ivory Lewis chessmen. It represents a beserker or knight which belongs to a set designed in the 12 th century by the Scandinavian school. Some of these nice little works of art can be found in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh and other ones in the British Museum.

My favourite source of information about Orkney is Sigurd Towrie’s Orkneyar, ‘a website dedicated to the preserving, exploring and documenting the ancient history, folklore and traditions of Orkney’. It is beautifully illustrated and full of tales, myths and legends.

In 1098 Orkney earldom was divided between two brothers, the earls Paul and Erlend. Magnus was the eldest son of Earl Erlend and his cousin Hakon was the son of Paul. That same year, Magnus ‘Barelegs’, the Norwegian king, came to Orkney and after unseating both earls he made Sigurd, his illegitimate son, overlord of the islands. When Sigurd returned to Norway he left the earldom to Hakon until Magnus came back to Orkney to claim his share of the earldom. The two cousins reigned together peacefully for a few years but with the help of bad guys and malevolent gossiping things began to deteriorate. War was about to break out but a peace meeting was organized in Egilsay at Easter. Hakon’s betrayal led to the killing of Magnus on 16 April 1118.

Collection of painted panels in St Magnus Cathedral © 2012 Scotiana

Mounted on the organ wooden screen which you can find in the choir of St Magnus Cathedral there is a collection of very moving painted panels which read like an illustrated book. These panels which depict the events surrounding the martyrdom of St Magnus and the building of the cathedral were painted by children, 15 boys and girls, aged 13 years, from the Isle of Arran. They were presented on June 20th 1980 to the people of Orkney as a tribute to their festival, which is named after their patron saint, St Magnus.

Each of these lively and colourful paintings are described in a central panel.

St Magnus cathedral painted panels ‘divided loyalties’ © 2012 Scotiana

‘Earl Magnus and Earl Hakon become joint rulers of Orkney. Peace is broken between the cousins because of the malice of Hakon’s evil friends. Noblemen arrange a treaty and Magnus agrees tor a meeting in Egilsay, while Hakon plans treachery.’

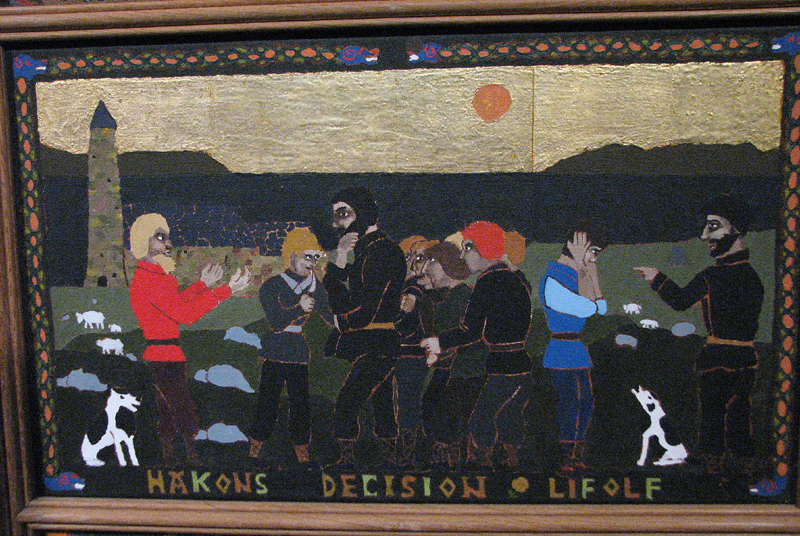

Painted panel ‘Hakons decision and Lifolf’ © 2012 Scotiana

‘Magnus is brought face to face with Hakon, and dissuades his cousin from his plan of murder. But Hakon’s men will not see their prey escape and they threaten Hakon himself. So, forced to proceed with his plans, Hakon selects his cook Lifolf to murder Earl Magnus.’

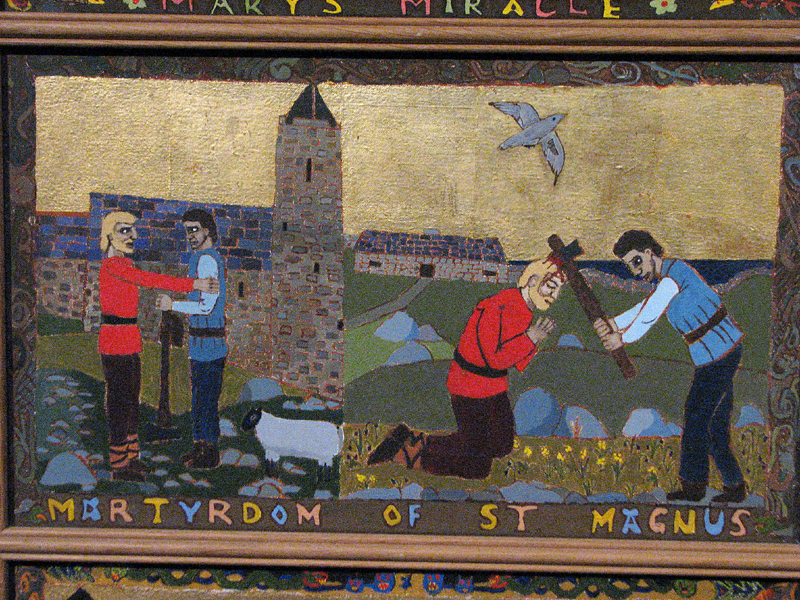

Painted panel ‘Martyrdom of St Magnus’ © 2012 Scotiana

‘Earl Magnus forgives Lifolf because he is only obeying orders. With a cheerful countenance he prays once more, then kneels to receive the blow from the axe. The place of the killing was stony, but it soon changes to green grass and flowers.’

Egilsay was the place where Saint Magnus was killed in 1118 by an axe blow to the head. While the church is dedicated to him, the foundation may be far older. For hundreds of years the story of St. Magnus, part of the Orkneyinga saga, was considered just a legend until (in 1919) a skull with a large crack in it, such as it had been stricken by an axe, was found in the walls of St. Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall.’

One spring morning all the peasants of Birsay were out on the bishop’s land, ploughing behind their oxen.

The land went in a gradual fertile sweep from the hill Revay to the shore of Birsay. Just off the shore was a steep green island, with a church on it, and a little monastery, and a Hall. A sleeve of sea shone between the ploughlands and The Brough of Birsay (as this island was called). Occasionally the peasants could hear the murmur of plainsong from the red cloister.

The wild geese flew over.

(George Mackay Brown – Magnus – Chapter 1 ‘The Plough’)

After his execution, Magnus was laid to rest at the church his grandfather had built at Birsay.

‘The rocky area around his grave miraculously became a green field, and there were numerous reports of miraculous happenings and healings. William the Old, Bishop of Orkney, warned that it was “heresy to go about with such tales”, then was struck blind in his Birsay cathedral and subsequently had his sight restored after praying at the grave of Magnus, not long after visiting Norway (and perhaps meeting Earl Rögnvald Kolsson).’

Source: Wikipedia

Plaque marking the burial place of St Magnus in a pillar, south of the organ screen © 2012 Scotiana

After being slain, Magnus’ body was brought back by his mother Thora by permission of Earl Hakon, now sole rule of the islands. He was laid to rest in his grandfather’s Christ Church on Birsay where the saga says his body lay buried for 21 years before Bishop William ‘admitted his sanctity’, papal recognition not yet being needed. Shortly thereafter, his remains were removed to Kirkwall where they were “set over the altar in the church that stood there. This is, as we have seen, believed to have been a church dedicated to the martyred Norwegian King Olav that has long since vanished – the only remaining part of which is now an arch, removed from its original position and today serving as a garden gate. It has been assumed that his shrine would be placed over the high altar in the new cathedral as soon as it was consecrated. It is further assumed that the consecration must have taken place in 1152/3, before Earl Ragnvald and the highest leader of the Orkney church, Bishop William, set out on their pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

(Sindre Vik’s thesis Written in Stone Chapter 4 ‘The Death of Earl Magnus’)

Inside one of the big pillars of St Magnus Cathedral the relics of St. Magnus are lying, not far from those of St Rognvald…

These two books, on sale in the cathedral, are excellent guides to visit the cathedral and if you’re lucky you will fall on the mysterious gentleman who made us discover some of the little secrets of the place… many thanks to him for without his help we would have missed the greenmen 😉

The Orkney Imagination is haunted by time.

George Mackay Brown

Let us leave the last word to the great Orcadian poet whose name is inscribed on a golden plaque, below a beautiful colourful stained glass window, on a wall of the St Magnus Cathedral, not far from the memorial of John Rae, the Orcadian Arctic explorer. Each of these men have left their marks in their own field of exploration… two lights shining in the North…

History both repeats itself and does not repeat itself. One event; one group of characters that move in and through and out of the event, and both make the event and are changed by it, collectively and individually – that event bears resemblances to another event that occurred a hundred years before, so that a man listening to a saga is moved to say, ‘This is the same performance all over again.’ It is not: the costumes have changed, the masks have changed, the gestures though similar have a new style, and the personages will soon go away into their own mysterious silence.

( George Mackay Brown – Magnus)

I am interested in facts only as they tend and gesture, like birds and grass and waves, in “the gale of life” (…)

The facts of our history – what Edwin Muir called The Story – are there to read and study: the neolithic folk, Picts, Norsemen, Scots, the slow struggle of the people towards independence and prosperity. But it often seems that history is only the forging, out of terrible and kindly fires, of a mask. The mask is undeniably there ; it is impressive and reassuring, it flatters us to wear it.

Underneath, the true face dreams on, and The Fable is repeated over and over and over again.

(From George Mackay Brown An Orkney Tapestry – Foreword)

Bonne lecture !

A bientôt.

Mairiuna.

Leave a Reply