Bonjour Marie-Agnes, Janice et Jean-Claude –

Ca va bien? – How are you all today? 🙂 Margaret and I love to read all the letters you send us, so full of kindness and bonhomie! Our readers here at Scotiana may not know that your letters are in fact doubly charming, for they are always illustrated! (As you have often said, Mairiuna, “une photo vaut mille mots” – one picture is worth 1,000 words.) Beatrix Potter (1866-1943) comes to mind here, author of one of the most famous ‘picture letters’ in history – this is her 150th Anniversary year. Writing to a small boy who was ill – Noel Moore, eldest son of the lady who had been her last governess – Beatrix first revealed to the world that she had conceived of a story about ‘four little rabbits, whose names were Flopsy, Mopsy, Cottontail and Peter’. Around the margins of the letter, as you might imagine, were delightful sketches of them all, for Beatrix Potter had become an accomplished artist.

The Tale of Peter Rabbit first appeared on 2 October 1902, and was an immediate success. By 1905 Miss Potter had settled in the Lake District in the North of England, where she became increasingly interested in farming and rural conservation. As the perceived danger to the countryside increased, from industrialisation and urbanisation, she gave more and more generously to the National Trust (which had actually been founded in 1895).

Our own National Trust for Scotland dates from 1931 and manages a huge portfolio of properties, ranging from estates of thousands of acres to stately homes and castles, from the splendour and awe of Glencoe, Culloden or Bannockburn to the ‘little houses’ of Culross, Fife. But one of the most accessible, by far, must be Miss Toward’s wee tenement flat, just a few hundred yards from the shops of Sauchiehall Street and the iconic Glasgow School of Art. Let’s go up and pull the bell, and see if anyone has remembered to put the kettle on!

…………………………….

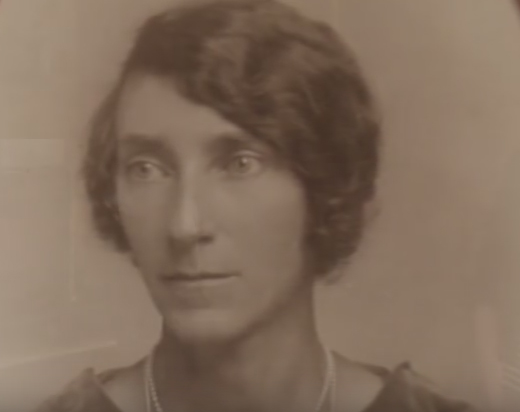

Miss Agnes Toward was tiny, genteel and tended – according to those who remembered her – to keep herself to herself. She was also one of life’s squirrels, an inveterate hoarder of domestic trivia.

Viewed from the outside, the flat Miss Toward occupied for 54 years, at 145 Buccleuch Street, Glasgow, is indistinguishable from its neighbours, two-room and kitchen homes built in 1892 in the city centre just north of Sauchiehall Street. Inside, it is a treasure-house for the social historian.

After 10 years in hospital Agnes Toward died in 1975 in her eightieth year, never to know that her modest home would be purchased by the National Trust for Scotland, and opened to the public alongside the great historic houses in its care.

When the rent for the first-floor flat ceased to be paid, lawyers established that there were no living relatives. The factor for the property was about to follow the usual procedure, instructing the cleansing department of Glasgow District Council to clear out the contents. But first, an elder from Wellington Church in the West End called to collect six dining-room chairs bequeathed to him in gratitude for his help in Miss Toward’s later years. With him was his niece, the actress Anna Davidson.

Miss Davidson, speaking at her home in Glasgow, described to me her feelings when she entered the flat for the first time :

“I felt like Pip in the film of Great Expectations when he stood at the door of Miss Havisham’s room. Under layers of dust Miss Toward’s flat was exactly as it had been ten years earlier when the door closed behind her for the last time.The box bed in the kitchen was covered with cobwebs, but the stone hot water bottle was still between the sheets. There was washing on the pulley suspended from the ceiling, coal in the wooden bunker, jars of jam in the cupboards and unwashed iron pans on the cooking range. Every room was filled with the personal possessions of Agnes Toward and Mrs.Toward who shared the flat with her daughter until she died in 1939. I knew I just had to save all this for posterity and I decided there and then to buy the flat – though I already had a place of my own.”

For seven years Anna Davidson lived alone in the flat dusting and scrubbing and tidying up. In 1982 she approached the National Trust for Scotland, hoping they might know of a private buyer interested in preserving Miss Toward’s home intact. To her delight the Trust offered to buy the flat.

In April 1983 the Tenement House was officially opened by the Glasgow author Cliff Hanley, a life-long tenement dweller himself. The brass bell-pull at the front door jangled as each guest arrived, the wag-at-the-wa’ clock was ticking, the gas lamps hissed, a coal fire glowed in the black grate and the polished round table in the dining room, heavily draped with chenille, was set for afternoon tea with scones and Dundee cake. The musical score of Annie Laurie lay open at the rosewood piano – labelled as having been purchased from Laubach and Sons of Edinburgh.

The only major change to the flat made by the National Trust was the restoration of gas lighting. Encouraged by Anna Davidson’s uncle, Miss Toward had succumbed to the convenience of electricity in 1960. Otherwise the flat is similar to many thousands of Glasgow tenements of some architectural merit built for aspiring middle class families when Glasgow was the Second city of the Empire.

Approached through a ”’wally close ” – a tiled common entrance and stairway – it consists of a hall, parlour, bedroom and kitchen. A small bathroom with hot and cold running water set it apart from the working class tenements where families shared outside facilities.

But in Victorian times the professional people and shopkeepers who lived in Garnethill could have families as large as the poor, and in Miss Toward’s house each room had sleeping accommodation. In the bedroom there was a brass bed covered by a patchwork quilt, in the parlour a double box recess bed with doors which would be closed if the family had visitors; and in the kitchen another box bed with a curtain. Most tenement families would keep a square ‘hurly bed’ which fitted under the parlour bed, to be ‘hurled’ out when the smallest children were laid down to sleep. Whoever went to bed last would occupy the bed in the kitchen where the family sat and ate except on Sundays. The kitchen was the cosiest room, for its coal-burning range was never allowed to go out.

Recess beds could be awkward to make up, so a stick with a hook for pulling up the bedclothes would hang nearby. A low stool was also kept handy to enable the children to climb in. Box beds were banned by the local authority in 1901 but they were hard to remove and many remained in place for a number of years later, though probably few as long as Miss Toward’s.

Although the Toward ladies never had servants at 145 Buccleuch Street, there is still a bell handle in the parlour connecting with a dangling bell in the kitchen. (Before the First World War when over-crowding in the less salubrious of Glasgow’s tenements was so bad that the town council devised a system of ‘ticketing’ to regulate the number of tenants to a room, poor families were only too glad to send their daughters from the age of 14 or so to domestic service in a respectable house.)

Agnes Toward, an only child, was born in nearby Renfrew Street, in September 1886. Her father, William Toward from Bonhill, Dunbartonshire, had built up a thriving metal merchant’s business in West George Street at a time when Glasgow was an important centre for the iron industry. He died when Agnes was just three years old. Mother and daughter lost the family home and lived at various addresses – always in Garnethill – until they settled down in affordable accommodation in Buccleuch Street, then an address for the aspiring middle classes. To make ends meet Mrs Toward was a dressmaker for private clients and from time to time she would take in a lodger.

Throughout Agnes’s childhood, Mrs Toward seems to have lived in a sort of genteel poverty compared with the old days. State pensions for widows were not available until 1925 and there was no comprehensive scheme for social security until 1945. Documents found in the house show that Mrs.Toward had to accept occasional assistance from the Glasgow Benevolent Society and from the charitable Hutcheson’s Hospital.

After leaving school Agnes took a shorthand and typing course at the Glasgow Athenaeum commercial college and found employment with Miller and Richards, a shipping firm doing business with the West Indies. She nursed her mother for several years until she died at the age of 81.

As a tenement-dweller Agnes had certain communal responsibilities.

In the shared back yard there was a communal wash-house with china ‘Belfast’ sinks, a boiler and a heavy mangle. According to the factor’s regulations found among Miss Toward’s papers, the wash-house was to be used by residents in rotation on stated dates once a month. The rules concerning the communal stairs and the ‘close’ (the tiled entrance to the building) specified sweeping every morning and washing at least twice a week by each resident in turn, those living in the higher flats attending to the stairs below their own homes, and those on the gound floor being reponsible for the close.

Miss Toward also had to remember to keep her coal bunker full, setting up the coal merchant’s card at her front window with a figure to let the lorry driver know how many bags she required.

A daily chore was the cleaning of the cast-iron range in the kitchen which supplied heating, hot water and cooking facilities. Miss Toward used Zebo black leading liquid, then burnished the metal with an emery cloth and steel chain pad. In the cupboard under the sink she kept household aids such as Monkey Brand soap, ammonia, Ezelite firelighters, Hudon’s soap powder and Mothicide. In the brush cupboard was her cane carpet beater, the Ewbank sweeper and a straw broom for the stairs.

Miss Toward continued to work outside the home until she was 73, in later years for another shipping firm, Prentice, Service and Henderson. Yet she found time to do all her own cooking and home baking. She left jars of home-made rhubarb jam dated 1963 alongside The Be-ro Book of Home Recipes, Cox’s Manual of Gelatine Cookery, a bottle of John Jaap’s quintessence of lemon, Primrose olive oil and Tate and Lyle preserving crystals. In the drawer of the kitchen dresser, a wooden spurtle for stirring porridge and a ‘tattie champer’ for mashing potatoes lay among the knives and serving spoons.

For special occasions Miss Toward placed orders with Manuel and Webster, a high-class delicatessen. In their catalogue for 1938 a roasted chicken cost 8s 6d. a Christmas cake 3s 6d, whisky was 12s 6d and tartan boxes of shortbread decorated with white heather 5s 6d.

According to a declaration of income in Miss Toward’s handwriting for 1936 she was earning 47s 6d a week. A Paying Patient’s Account from Canniesburn Auxiliary Hospital for 1944, four years before the establishment of the National Health Service, stated that board, residence and nursing for one week cost Miss Toward three guineas. With the addition of 2s 6d for fruit juice, her total bill came to £3 5s 6d.

Miss Toward made sure her medicine cupboard in the bathroom was well stocked with the home remedies of her time – Zambuk for soothing cuts and grazes, boracic acid, Hobson’s Choice plasters for the feet, iodine solution and eucalyptus oil.

From early childhood Agnes kept records of Christmas, New Year and birthday presents given and received ; and prizes and certificates for school work well done – she excelled at needlework. She had a 10s 6d child’s season ticket for the second Glasgow International Exhibition in Kelvingrove Park in 1901 – when the city was at the height of its importance for manufacturing and was exporting around the Empire iron and steel products,ships and locomotives. In 1938 she was one of almost 12 million visitors to the Glasgow Empire Exhibition in Bellahouston Park, the last of Great Britain’s renowned international trade exhibitions.

As a child Agnes learned to play the piano and had dancing lessons in the Queen’s Rooms in La Belle Place. Later she was a member of the fashionable Wellington Church in University Avenue, paying an annual rent of 8s 6d in the 1960s for one sitting in Pew no.120. She had her own visiting card and kept a small bank account. She supported the Conservatives.

Miss Toward’s drawing-room in Glasgow Tenement House Miss Toward’s drawing-room © National Trust for Scotland

When broadcasting began Miss Toward bought a battery wireless and listened to comedy programmes such as ITMA and the McFlannels. In 1953 she told friends in Canada that she had watched the Coronation on television at a neighbour’s house from ten in the morning until six in the evening.

Throughout her life she loved the theatre – and in the 1950’s Glasgow was, in the words of the New York magazine Variety “the most theatre-minded city in Britain”. In 1952 she enjoyed a performance of Mr Wu by the Wilson Barrett company which played regularly in Glasgow until 1954.

In a letter dated 19th November 1958 to her Canadian friend, she mentioned having a staff night out at the King’s Theatre to see Kenneth McKellar in Old Chelsea, a musical comedy by Richard Tauber, the Austrian tenor.

Miss Toward always spent her holidays at one of the Clyde Coast resorts, the choice of most Glasgow people until package tours to foreign destinations killed the paddle steamer trade. In 1908 she stayed at Kirn with her mother and grandmother. The ladies rented a room and kitchen and had to buy a bag of coal for the fire to get hot water. It was customary then for holidaymakers to take ‘rooms with attendance’ – which meant buying their own food for the landlady to prepare, an early form of self-catering. In later years she travelled by train to west-coast resorts, usually Largs. She would consult Murray’s Timetables which gave train times and fares for First and Third class – for some inexplicable reason there was no Second Class. She left from the ornate St Enoch’s station (demolished in 1977) the point of departure for the L.M.S. (London Midland and Scottish) trains which served south-west Scotland before the private railway companies were nationalised in 1948.

Recently the stone front steps of 145 Buccleuch Street were found to be in need of repair, worn down by around 20,000 visitors a year. The volunteer guides have a fascinating story to tell – most of them were brought up in Glasgow tenements themselves. In the very early days some of them – and a few visitors – had actually met Agnes Toward.

“A little, shy person” one visitor recalled “always respectably dressed in brown or black. But there really isn’t much to tell. She always had this tendency to keep herself to herself and as the years passed she saw fewer and fewer people. In the end it must have been a house where the door was hardly ever opened to a visitor.”

Copyright Margaret Henderson, 2015.

******************************************************************************************************************

We hope you manage to visit the Tenement House one day! 🙂 🙂

A bientôt.

Margaret and Iain.

Many many thanks, dear Margaret, for this very interesting trip back in time and such a lively page of Glasgow social history. We look forward to visiting Miss Toward’s flat in Glasgow.

Dear friends, we are always so eager to read your wonderful “Letters from Scotland”.

As you’ve just mentioned, Iain, this year we celebrate the 150th birthday anniversary of Beatrix Potter (July 28 th 2016). Is it not a good time to rediscover her lovely illustrated little books? We’re great fans of this very talented English artist who loved Scotland so much. Last year, it is with great pleasure that we revisited “Beatrix Potter Garden & Exhibition” in Birnam, near Dunkeld. It is situated not far from Dalguise where young Beatrix Potter used to spend her summer holidays with her family, a happy time for her.

We are very grateful to the National Trust for Scotland and to Mr Glen Bowman for accepting so kindly to share their pictures with us.

But the kettle is on, let’s go now 😉

Encore un grand merci à Iain et Margaret pour leurs merveilleux écrits.

A bientôt.

Mairiuna.

Let’s go up and pull the bell, and see if anyone has remembered to put the kettle on!

(Iain)

https://youtu.be/3K8tsBiFuig

https://youtu.be/K-BIz8KIjQA

https://youtu.be/kbryo5AcUQM

https://youtu.be/LISZXCsRm_0

Excellent article. I have visited the Tenement House a few times, but not recently. I must go back inspired by all this background info!

We visited here yesterday & enjoyed it very much indeed.

It reminded me of my Aunt Sadie’s tenement flat in Possilpark, though being a step up from hers in having a bath.

I was distressed to think of her spending 10 years in Gartloch Hospital as I spent a month as a student nurse on secondment there (from Glasgow Royal Infirmary) in the 1970, & found it a truly dreadful place.

Fascinating! My last name is toward and I never knew this existed.