Bonjour Marie-Agnes, Janice et Jean-Claude ! 🙂

Hello again from Scotland !

Is there, I wonder, any more romantic story in all of our country’s modern history than the tale of ‘The Stone’ – how at Christmas 1950 Ian Hamilton (b.1925) and some young friends removed Scotland’s Stone of Destiny from Westminster Abbey to bring it back home? What they did was, of course, illegal, but was it wrong? – for the English (under Edward I), during one of their many raids, had in 1296 taken by force the Stone upon which Scottish kings had been crowned for more than four centuries. And although a later peace treaty had obliged them to return it, they refused to give it back.

I’ve chosen this moment to write a short account of these dramatic events of more than 70 years ago, for on 13 September Mr Hamilton will have his 96th birthday!

I’m sure I join with thousands, both in Scotland and around the world, in wishing you, Mr Hamilton,

many happy returns of the day, and plenty more happy years to come! 🙂

.

We don’t ‘do’ politics at Scotiana, but judged as a historical event it’s abundantly clear to me that the returning of the Stone of Destiny to Scottish soil in the early days of 1951 set our country firmly on the path to self-government. Looking back, the achievement was more than a simple milestone, for we now see that it was one of the more prominent landmarks on the way. As you have said, Mr Hamilton, to be able to do something like this for one’s country – and without spilling a drop of blood – is a wonderful thing. Your heroic actions, and those of your young friends, will not be easily forgotten. ‘De tout coeur, Merci’ – From the bottom of our hearts, we thank you. 🙂

.

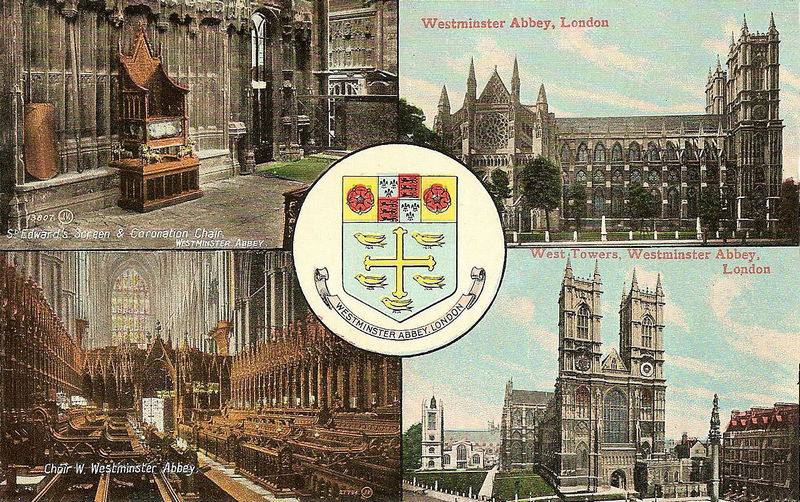

As a symbol and badge of Scottish nationhood, the Stone of Destiny is without equal. Taken south and installed under the Coronation Chair in Westminster Abbey, English and British monarchs had in turn been crowned upon it for 650 years – so we can easily understand the reaction when the Stone was suddenly found to be missing! For weeks, it seemed, the newspapers reported little else.

.

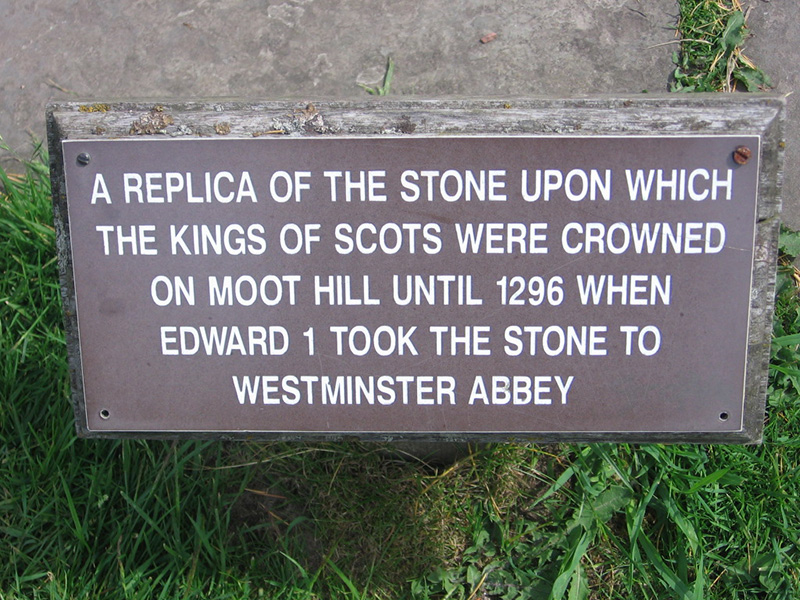

Scone Palace Chapel – Replica of the Stone of Destiny © 2006 Scotiana

.

Scone Palace Moot Hill – Stone of Destiny repliqua plaque © 2006 Scotiana

The act of recovering the Stone was undeniably audacious. More than that, it had called for real courage, bordering on recklessness, for the young people concerned were starting out on their careers and would risk criminal convictions if caught, as seemed quite probable. The curious thing, perhaps, is that they had no clear plan as to what they might do with the precious Stone – other than keeping it safe – once they had succeeded in bringing it back to Scottish soil. But its return was a Triumph, a hugely symbolic act which for years fired the imagination of Scotland’s people, rich and poor alike.

Our country’s self-awareness as a nation had been growing since the end of the Great War in 1918, but this increase was from a very modest starting-point. Incredible as it now seems, it had been quite acceptable even in late Victorian times to refer to the lands across the River Tweed as North Britain! It was as though Scotland had died and become just another part of Britain, like Kent or Yorkshire.

Edinburgh Scottish Parliament Debating Chamber – Wikipedia

John MacDonald MacCormick

Dear Friends, now that we have a Scottish Parliament again with substantial powers, I wonder if modern Scots realise just how much they owe to John M MacCormick (1904-1961), the Glasgow lawyer whose name is scarcely remembered today, yet who devoted the best years of his life to the struggle for Home Rule? MacCormick was a passionate and inspired speaker whose leadership prepared the groundfor so much that we now enjoy.

John MacCormick first gained prominence in April 1928, when – not yet 24 years old – he founded the National Party of Scotland, committed to working for Self-Government. (It cannot be a coincidence, I think, that in the very next year – 1929 – the position of Secretary of State for Scotland was created. For the first time, a minister would sit in the British Cabinet, at the heart of government, charged with representing Scotland’s interests.)

By 1932 the National Party faced a more right-wing rival, the Scottish Party – but largely due to the personal influence of MacCormick, the two were brought together in 1934 to form the modern Scottish National Party (SNP). Inevitably there were occasional disputesand even bitter disagreements within the early SNP, but its settled policy at first was to campaign for Home Rule for Scotland, rather than Independence.

Matters came to a head in 1942, when after an internal struggle this key policy was reversed. Sadly, John MacCormick felt obliged to resign from the party that he had helped to found eight years earlier. Taking many supporters with him, he established a new group, the Scottish Union, later to become the Scottish Convention. Wisely, perhaps, he judged that the best tactic at that time would be to build the widest possible coalition, drawn from all sections of society, in support of Scottish Home Rule.

Scottish Covenant Association Insignia.svg

Under MacCormick’s leadership, the Convention set themselves the task of drawing up a Petition calling for Self-Government, ideally to be signed by every adult in Scotland and to be known as the Scottish Covenant. By October 1949 the final text was agreed, and thework of collecting signatures began. (Members of the Scottish Convention had met in Edinburgh, at the Church of Scotland’s Assembly Hall on The Mound.) Soon the Scottish Convention became known as the Scottish Covenant Association, and its supporters as Covenanters.

The agreed text of the Scottish Covenant – the Petition – ran as follows :

“We, the people of Scotland who subscribe to this Engagement, declare our belief that reform in the constitution of our country is necessary to secure good government in accordance with our Scottish traditions and to promote the spiritual and economic welfare of our nation.

We affirm that the desire for such reform is both deep and widespread through the whole community, transcending all political differences and sectional interests, and we undertake to continue united in purpose for its achievement.

With that end in view we solemnly enter into this Covenant whereby we pledge ourselves, in all loyalty to the Crown and within the framework of the United Kingdom, to do everything in our power to secure for Scotland a Parliament with adequate legislative authority in Scottish affairs.”

Little kiosks and stands were set up in busy streets and other public places, and within six months half a million people had signed the petition for Home Rule, the Scottish Covenant. (Two million would eventually sign by the end of the campaign in 1951, from a total population of just over five million, impressive evidence of how public opinion could be changed.)

Ian Hamilton judged that a spectacular ‘coup’ – such as the taking of the Stone – would be invaluable in sending a rallying-call to the Scottish people, a reminder to them after so many years that they were a Nation and ought to take charge of their own affairs. The decision to recover the Stone of Destiny was Ian’s alone. He did not even consult his parents (who had retired to Ballinluig, Perthshire, from the Paisley area, where they’d had a tailoring business). At 25 years of age he had gained a certain maturity, and as a student of law he had often thought of the purposes and limits of legal power. In the end, the affair was for him a matter of conscience – he would act as he felt compelled to, bravely accepting that he might face prison if convicted.

Mr Hamilton first told his story in detail in the book that he published in October 1952, ‘No Stone Unturned’. It’s a clever title, I think you’ll agree! Is there a French equivalent of this idiomatic phrase, I wonder? 🙂

No Stone Unturned – The Story of the Stone of Destiny

Ian R Hamilton

191pp. Gollancz, London, 1952. Funk & Wagnalls, New York, USA, 1953.

The London publisher described the book as containing ‘The inside story of the disappearance of the Coronation Stone, by the Ringleader, Ian Hamilton’. An interesting foreword running to five pages was contributed by Sir Compton Mackenzie (1883-1972).

Mr Hamilton sent his book off to the press on 28 April 1952. As a preface, he addressed two paragraphs to English readers :

“I have not written this book out of any hatred for the English. On the contrary, I admire you very much. Having clung to your past, you have preserved your present, and your passionate nationalism has made you the greatest nation in the world. My only complaint is against the Scots. Had my people remembered that to be Scottish is not better or worse than being English, but only different, the Stone of Destiny would not have been about our necks, and Anglo-Scottish relations would not be embittered by administrative bickering .. “

Ian Hamilton acknowledged his particular debt to John MacCormick, ‘without whose genius little worthwhile would be done in Scotland’. As Chairman of the National Covenant Association MacCormick was a popular national figure, and had been elected in the autumn of 1950 by the students of Glasgow University as their Rector (their representative in the University Court, the governing body). Ian Hamilton had led the rectorial campaign on behalf of Mr MacCormick and would come to know him well. Despite an age-gap of 20 years, theirs was a friendship that nothing could shake.

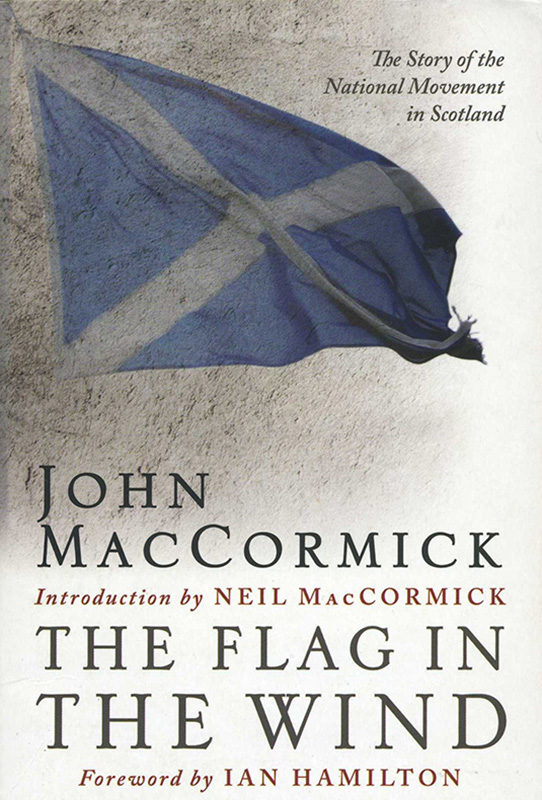

John MacCormick narrated the early history of Scotland’s National Movement in his book of 1955 (republished 2008) :

John MacCormick The Flag in the Wind Birlinn 2008

The Flag in the Wind : The Story of the National Movement in Scotland

Gollancz, 1955. Birlinn, 2008, Paperback. ISBN 97818 4158 7806

The film “Stone of Destiny” also came out in 2008.

Sadly, it was not commercially successful, but that’s another tale. Its release was accompanied by an updated edition of Mr Hamilton’s book :

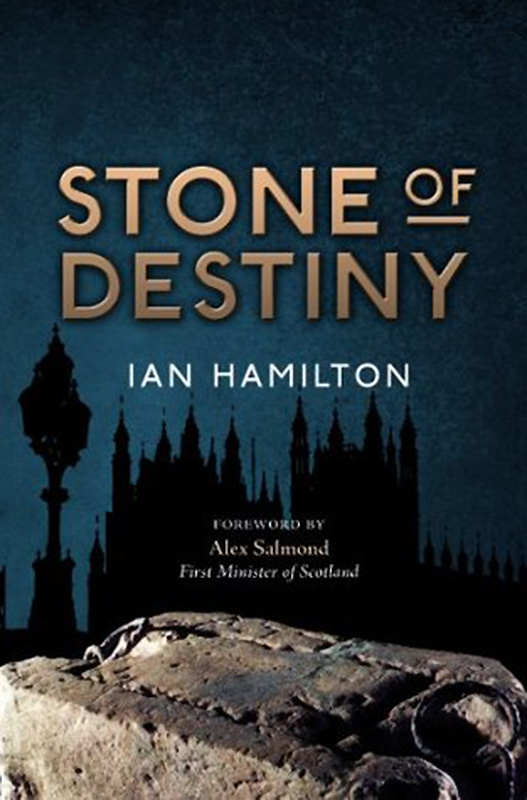

Stone of Destiny Iain Hamilton e-book

Stone of Destiny – The True Story Ian Hamilton

Birlinn, 2008, Paperback, 213pp. ISBN 97818 4158 7295

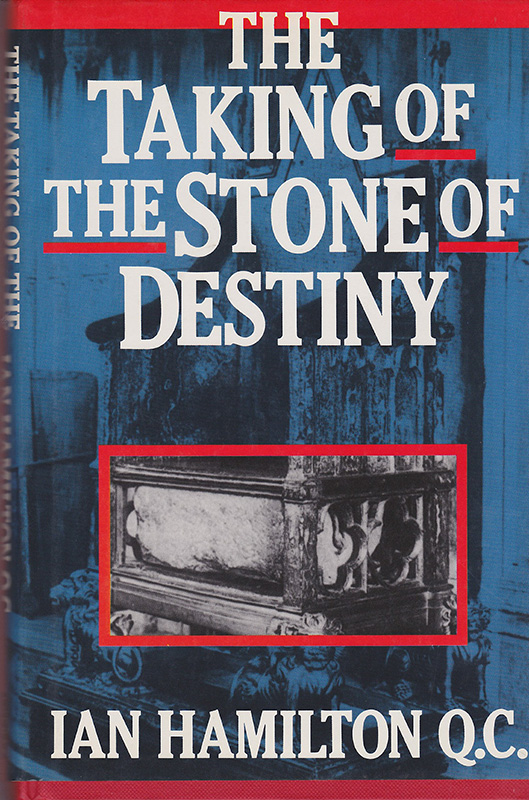

A second hardbound edition of Ian Hamilton’s book had appeared in 1991, in a larger format and with eight pages of photographs :

The Taking of the Stone of Destiny Ian R Hamilton QC

Lochar, 1991, 203pp. ISBN 0-948403-24-1

Ian had to confirm that his plan to raid the Abbey was feasible and that any foreseeable difficulties could be overcome. Failure was unthinkable, because bad publicity would damage the Covenanters’ cause greatly. To this end, he had travelled down alone to London by train a week or two before Christmas, visiting Westminster Abbey again while paying particular attention to the location of the doorways and the layout of the surrounding lanes. He found that the great church was deserted after dark, except for the patrols made by a single watchman. And the streets, too, seemed little guarded at night.

Mr Hamilton had tried to learn all he could about the Stone, consulting every relevant book in the Mitchell Library. He signed the slips requesting these books in his own name, making no effort to cover his tracks. (When, months later, the police investigated him, the issue slips were one of the few pieces of ‘circumstantial evidence’ they found.) Ian read the history and all of the legends clinging to the Stone of Destiny, and even discovered its precise dimensions – 26.75 inches long, 16.75 inches wide and 10.75 inches tall. But what was its weight? He guessed about three hundredweights (336 pounds). Discussing this one day with John MacCormick, the older man reached for his telephone. ‘Bertie Gray’s the man,’ he said. ‘He knows more about stone than anyone else in Scotland.’

Robert Gray (1895-1975) was a remarkable man. He had given distinguished service in the Great War, rising to the rank of Major – a title he did not use in civilian life. Usually he was spoken of as Councillor Gray, for he was an elected member of Glasgow Corporation(the City Council) and a Baillie (Magistrate). A passionate believer in Home Rule, he had been a founding member of John MacCormick’s National Party of Scotland in 1928 – and now, in 1950, he was MacCormick’s deputy as Vice-Chairman of the Scottish CovenantAssociation. (Together, John MacCormick and Robert Gray financed the young people’s project.)

Bertie had studied the craft of stonemasonry. Successful in business, he had built up his own firm producing grave-stones and other memorials. He drove Hamilton up to his yard at Lambhill Cemetery (in the north of Glasgow), where Ian discreetly made his way over to the spot indicated. “There, among the long grass, lay a replica of the Stone of Destiny. It was 20 years old. It had been made in the late 1920’s in connection with another plot to recapture the Stone, a plot that never came off. Lying on the ground, it looked much bigger than I had imagined. ‘It weighs four hundredweights,’ Bertie told me.” (Stone of Destiny, 2008)

The Team

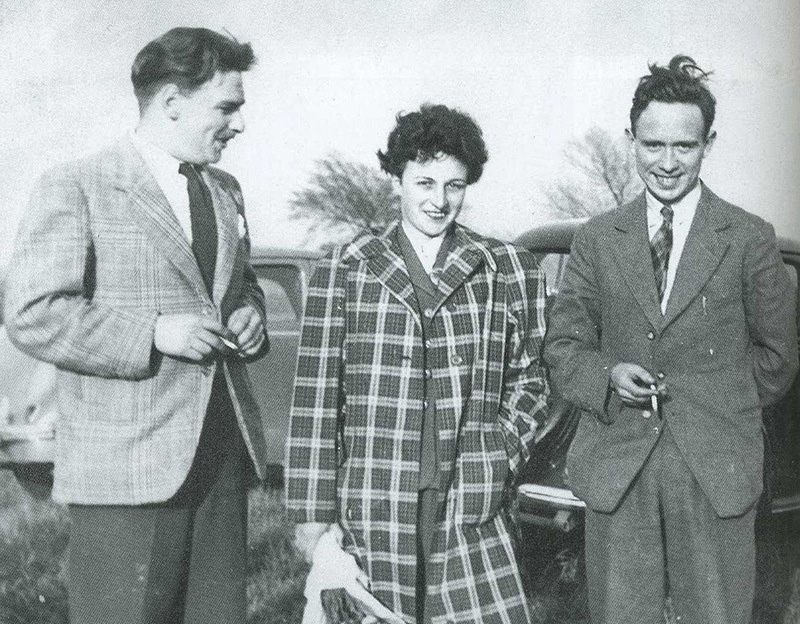

Gavin Vernon, Kay Matheson and Ian Hamilton from Stone of Destiny – Ian Hamilton – Birlinn 2008

To execute his plan, Ian Hamilton set out to recruit a small team of helpers. One of the first he approached was a girl, Kay Matheson, whom he knew to be a fellow Covenanter and someone he judged to have the necessary personal qualities of discretion, determination and commitment. Ian was never romantically involved with Kay, but it’s clear from what he has written that he admired tremendously her courage and self-reliance.

Kay was a Highlander and a native Gaelic speaker. Born on 7 December 1928 and baptised Katrine Bell Matheson, she was from Inverasdale in Wester Ross. Historically, her forebears had been victims of the cruel Highland Clearances. Kay may have studied at the University of Glasgow, but I cannot confirm this. In any event, by the time she eagerly offered to help in raiding Westminster Abbey during the University Christmas vacation of 1950, she was 22 years old and employed as a teacher at Achtercairn School, Wester Ross.

After discreetly ‘sounding out’ a few more friends, Ian enlisted a third member of the team – Gavin Vernon, a doctor’s son from Kintore, Aberdeenshire, and a student of electrical engineering. Gavin, another Covenanter, was 24 and strongly built – a useful qualification, for Hamilton described himself as weighing only nine and a half stones! The team needed a reliable means of transport, and it was arranged that Gavin would hire a small eight horse-power Ford car from Wylie and Lochhead’s garage in Pitt Street. The vehicle turned out to be 12 years old and a pre-war model, but it was the best they could afford, for their funds were very limited. (In total, no more than about £100 was spent – a little over £3,500 today.)

Bertie Gray,Gavin Vernon, Ian Hamilton and Ian Stuart holding the national flag (The Herald & Evening Times picture archive) from “Stone of Destiny” By Ian Hamilton Birlinn 2008

At their last meeting before setting off for London, Gavin turned up quite unexpectedly with a friend who begged to be allowed to take part – this was Alan Stuart, just 20 years old and from Barrhead, Glasgow, a student of civil engineering. Ian Hamilton was furious, fearing that Gavin had been talking carelessly, but was soon won over by Alan’s engaging personality as well as the arguments of the others. Alan was tall and strongly built and would bring extra muscle-power to the project. But equally importantly he would bring a second car, a Ford Anglia, a contribution which was to prove of critical importance.

The young people had made only the most tentative plan. For success, it was essential that no warning of their raid should be given, and that after the Stone had been recovered, it should be hidden or taken from the city as quickly as possible. (The police did not have modern communications, but relied heavily on the telephone). One early idea had been to transfer the Stone to a large and powerful car, hired in London, which would take it to be hidden on Dartmoor (Devon).

Ian Hamilton had gained a good general knowledge of the Capital, and had made earlier visits to Westminster Abbey while stationed in England with the RAF (from which he was released only in 1948). Usefully, too, he had become familiar with the roads linking Scotland with the South while travelling home on leave by motorcycle. But with so many uncertainties and challenges still ahead, there was no time to lose if the young Covenanters were to have the best chance of accomplishing their mission before the Christmas holidays ended.

Multiview postcard of Westminster Abbey -Valentines before WWI

Raids on the Abbey, 23-25 December

Preparations made, the four set off about seven in the evening on Friday 22 December. All were drivers and would take turns at the wheel. Progress was slow, for the road network was poor and snow-bound. (Long-distance travellers in 1950 took the train.) They drove all night, reaching London exhausted early on Saturday afternoon. The 400-mile journey had taken 18 hours, and they had suffered terribly from the cold as their cars had no heaters. Even their warmest clothes and the extra blankets they’d brought along gave little protection in the winter temperatures.

As Big Ben struck 5.15 that Saturday, Ian and Gavin approached the Abbey to make a first attempt. Ian would aim to remain concealed inside after the church had been closed up for the night, admitting the others without causing any damage. With Gavin’s help a suitable hiding-place was found under a cleaner’s trolley. Soon Westminster Abbey was in darkness. Silently, Ian began to explore his surroundings, but hardly had he taken three steps when he was caught in the torch-beam of the night-watchman, a tall, bearded figure!

The watchman did not call the police, but treated Ian with courtesy, even kindness, asking whether he had enough money to pay for a bed that night. Not long after 6pm, however, Ian Hamilton found himself ejected from the Abbey. This failure was a disappointment and represented a loss of time. But more seriously, the next attempt at entry might have to be made by force. At that moment, though, the four agreed that they stood in need of a good square meal, and Christmas fare was on the menu! The night that followed, spent inthe cars, was again bitterly cold and no-one slept much as they waited for the first cafe to open, where they might find warmth and hot drinks.

Westminster Abbey under Full Moon Wikimedia

It was now Christmas Eve, Sunday 24 December. The plotters enjoyed hot baths at Waterloo railway station, struggling hard to keep awake. Much further reconnaissance of the Abbey followed in the afternoon, and yet another ‘council of war’ was held. A night-time raid was becoming unavoidable. Shrewdly, they learned of the movements of the sole night-watchman, and began to prepare their line of approach to the door at Poets’ Corner. Construction work was being done in this part of the Abbey, and the stone masons had erected a tall wooden hoarding so as to create a small yard in which they could work. To the young Scots, this offered the advantage that it screened the Poets’ Corner door from the street.

Kay had become ill through suffering a severe chill, but her condition improved quickly after some hours in bed at a small hotel. The others called for Kay at some unearthly hour, for she did not want to miss any of the action! The hotel-keeper may have become suspicious of the Scots’ nocturnal activities, for the police turned up and noted Ian’s particulars. They asked some routine questionsonly, but it was a concern that his car, the older Ford, had now come to their attention.

Just after four o’clock on Christmas morning Ian, Gavin and Alan approached the double doors leading to Poets’ Corner. Kay waited in the lane at the wheel of the Anglia. Ian carried a complete burglar’s toolkit and set to work, making as little noise as possible. The doors were of pine, a softwood, but were awkwardly secured from the inside by a padlock. Gradually though, the gap widened until the padlock yielded to Ian’s powerful ‘jemmy’ (a short crowbar). The way into the Abbey was open.

Passing the green marble tomb of Edward I, the three men reached the Stone. One held their torch, another prised at the sides of the Stone with the jemmy, while the third pushed hard from the back. It slid forward. Ian gave a last push from the back, Gavin and Alan struggling to take its weight between them. They staggered for only a yard or so, and had to put it down. The Stone was just too heavy. Attempting to lift it on to Ian’s heavy overcoat (made by his father), the conspirators were surprised but not dismayed to find that the Stone was actually in two pieces, making it less difficult to handle. A portion of about one quarter – and weighting around 90 pounds – had broken off. (This damage had possibly been caused on 11 June 1914, when Suffragettes bombed Westminster Abbey during their increasingly bitter campaign to win votes for women.)

Ian carried the smaller piece of the Stone to the car where Kay was waiting and hurriedly placed it on the back seat. Moments later – by a stroke of tremendously bad luck – a policeman appeared, coming their way! Ian covered the broken Stone with Alan’s spare coat. Then he leapt into the passenger seat of the Anglia and he and Kay embraced passionately, pretending to be young lovers who’d arrived in London too late to find accommodation. The constable seemed content that they were above suspicion, and the three shared a cigarette and some conversation. (This would be the policeman who, after the alarm had been raised, recalled ‘the girl with the green checked coat, and the boy with the tousled hair.’) They’d had a lucky escape.

UK satellite map maphill.com

After transferring the fragment of the Stone to the boot of the Anglia, Ian directed Kay towards Oxford, where she had a girl friend with whom she could safely leave the car. In the event Kay lost her bearings, but found herself on the road to Birmingham where – fortunately – another friend stayed who would be happy to help her. Ian returned to the Abbey, collecting on his way the second car from its parking place at Millbank. Through carelessly having mislaid the keys of the old Ford – and chatting to the beat policeman who had turned up – Ian was running dangerously short of time. There was no sign of Gavin and Alan as he arrived, but the larger part of the Stone lay ready for collection. Almost panicking, Ian heaved it into the small car. A few minutes later, he feared, the new watchman would be on the telephone to the police, reporting the break-in. Ian’s priority now was to drive, and drive quickly. Somehow, he found himself on the Old Kent Road – and, miraculously, there just ahead of him were Alan and Gavin, walking along together!

“One only, please,” said Ian, “the car is overloaded.” Gavin offered to return north by train. Alan ‘put his foot down’ on the accelerator and the small car raced towards Kent. Quickly they found a place to deposit the Stone, for it was now about 8.30 and well past dawn. Much later that day, just short of Rochester, Ian and Alan judged that they had found the perfect hiding place, a spot where it would never be discovered. They buried it in the soft earth, covering the top with litter and a thick layer of dead leaves. On the back of an envelope Ian made a sketch of the Stone’s location, to be sent to a trusted friend in Glasgow, for he knew that arrest was a distinct possibility.

University of Glasgow – Wikipedia

This trusted friend was a slightly older man and a particular confidant of Ian Hamilton, who chose not to be named in ‘No Stone Unturned’. Instead, a pseudonym was used. “I have called him Neil, because Neil was not his name,” wrote Ian intriguingly. As Mr Hamilton later disclosed, Neil was in fact Bill Craig, another ardent supporter of the Covenant, and the first with whom Ian had discussed seriously his plan to raid the Abbey. If only he had been less busy, Bill would also have been the first to volunteer. But as President of the Glasgow University Union that year (the students’ Social Club and Debating Society), his diary was full. He was heavily involved in organising events to mark the 500th Anniversary of the founding of the University, to be commemorated in 1951.

Dear Friends, our tale is almost finished – in as far as any story about the Stone of Destiny is ever finished! By a mixture of luck and good judgement, Ian and Alan avoided the police and returned to Glasgow without further incident. As you might imagine, they savoured the huge coverage of their ‘crime’ in the many newspapers then being printed. Phone calls to Bill Craig, coded at first, kept them abreast of public opinion in Scotland. Gratifyingly, it was overwhelmingly favourable. Bill passed on to the elated John MacCormick and Bertie Gray first news of the youngsters’ success in London.

Alan’s parents confirmed that Kay had evaded the police and made her way to her home in Wester Ross. And Ian soon came across Gavin Vernon at the Students’ Union – something of a Men’s Club in 1950, I would think. With so much police activity and virtually every driver being stopped and questioned, it was best now to remain in Glasgow for a few days, until the frenetic ‘hue and cry’ had died down – and wise, too for the young men to return to their usual ‘haunts’ as soon as possible, lest any long absence should be noticed.

Bill Craig joined Ian and Alan when they decided to return south on 29 December. The newcomer this time was Johnny Josselyn, a few years older than Ian, I think, but passionately interested in returning the Stone to Scotland. Somehow, Alan managed to get the use of a second car belonging to his father, an excellent large Armstrong Siddeley, luxurious when compared to the smaller Fords.

The four men completed the 1,000-mile trip to Rochester and back in heated comfort, with just a single incident of note. As they drew close to the hiding place of the Stone, it was clear that some travelling people had set up camp. Ian and Bill approached and asked if they might share the heat of the fire. Bill was a persuasive talker, and soon the conversation turned to matters philosophical – he spoke of freedom and justice, fairness and oppression. At length he explained why he and Ian had come to the field. Won over, the travellers helped Bill and Ian carry the heavy Stone to their car!

Ian Hamilton, John MacCormick and Gavin Vernon 20 April 2051 (The Herald & Evening Times picture archive) from Stone of Destiny by Ian Hamilton Birlinn 2008

Ian, Bill, Alan and Johnny were safely back in Glasgow by the last day of the year, Hogmanay, and delivered the precious Stone into the care of John MacCormick and Bertie Gray. Secretly it was taken to a hiding place, believed to be at the engineering works of Mr John Rollo (1901-1985), at Bonnybridge, Stirlingshire. (This, I understand, did not become known until after the death of Mr Rollo, who had given a long interview to the BBC on condition that it would not be broadcast during his lifetime.)

Kay’s part of the Stone was not returned to Scotland until the early days of 1951, when Ian Hamilton took the train down to Birmingham and drove back with it in Mr Stuart’s Ford Anglia. It was put into a big cardboard box at John Rollo’s factory, I think, while the larger portion was concealed behind some panelling.

As the police search for the raiders – and for the Stone – continued, MacCormick and the others resolved to petition King George. They offered to surrender the Stone immediately, if His Majesty would assure them that in all time coming it would remain in Scotland (and, interestingly, allowed that the Stone might be used in future coronations, whether in England or in Scotland). To deliver the petition, Ian Hamilton chose as an intermediary the Earl of Mansfield (1900-1971). Ian drove to Logie House to meet him, and the two had a pleasant conversation. But the government of Clement Attlee (1883-1967) offered no concession that they could trust.

By the middle of March, the Glasgow police had interviewed those who might be termed ‘peripheral suspects’ in the affair. (Ian Hamilton formed a high opinion of the man leading their inquiries, Detective Inspector William Kerr.) On 20th March Gavin and Alan were ‘taken in’ for questioning. Hearing this, Ian went along voluntarily. He was not arrested, nor did he admit to anything.

King George VI – Wikipedia

Public opinion remained firmly on the side of the young Covenanters, but John MacCormick detected a growing feeling that the precious Stone ought soon to be entrusted again to some public authority. It seemed wrong that it should be held secretly for months on end by any private individual. King George VI (1895-1952) was known to be greatly distressed by the taking of the Stone of Destiny, the British Coronation Stone. The King’s distress, I think, was decisive in causing the Stone of Scone to be given up.

King George was loved and deeply respected. He had represented all of his people during the Second World War while Mr Churchill, for all his ability as a leader, was more divisive, a political figure. Sympathy for the King increased greatly when it became known that he was seriously ill. It was agreed that the Stone would be returned, but first it would be given some expert repairs.

Bertie Gray arranged for the pieces of the Stone to be taken to the home of a friend at Bearsden, Glasgow. Here, in the garage, Mr Gray’s most highly skilled mason connected them using brass dowel pins, and filled the joint with a specially-made cement.

I shall give the last words to Mr Hamilton :

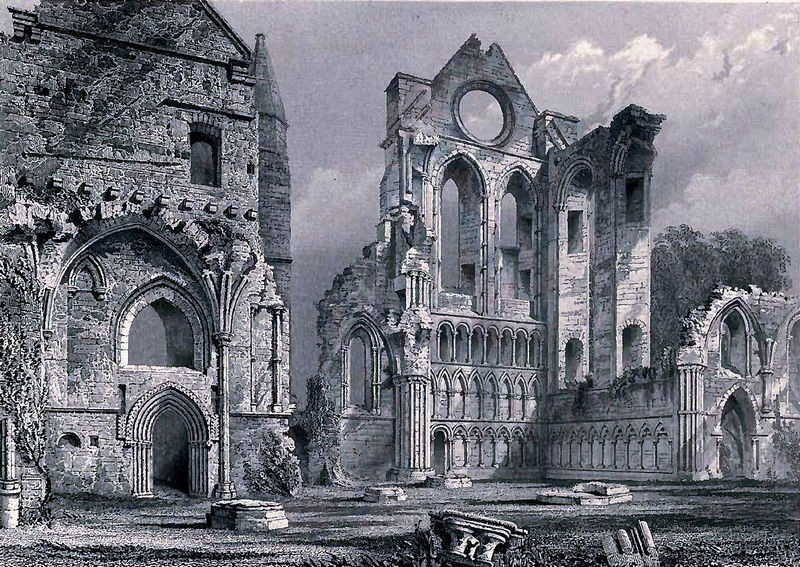

Arbroath Abbey from a drawing by R.W. Billings

“As the place to return the Stone, we chose the ruins of the great Abbey of Arbroath, where in 1320 the Arbroath Declaration had been signed by the lords, commons and clergy of Scotland .. .. On the morning of 11 April 1951, I left Glasgow with Bill Craig. At Stirling Bridge we thumbed a lift from a car driven by Councillor Gray, which contained the Stone of Destiny, now carefully repaired. At midday we carried it down the grass-floored nave of the Abbey and left it at the high altar .. “

On the revered Stone the three placed a blue and white Saltire, then turned away and stood for a moment at the gate.

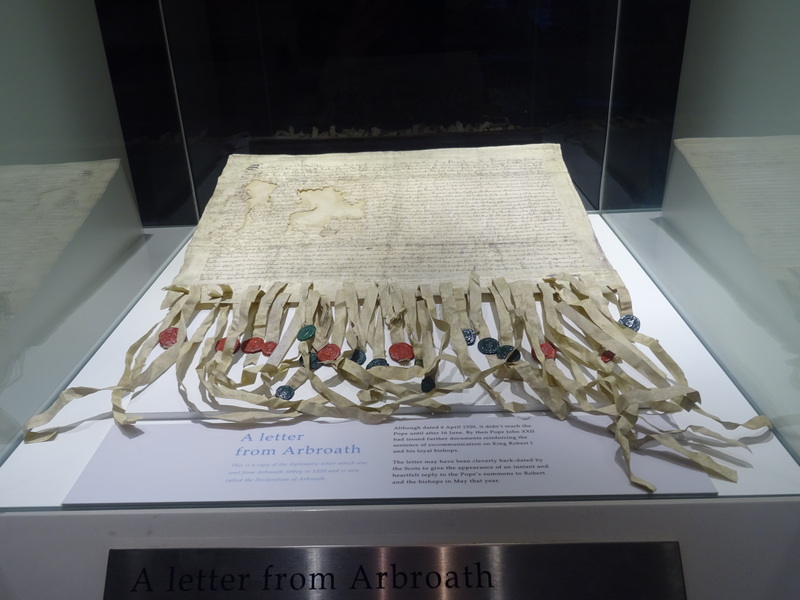

Arbroath Abbey Copy of the Declaration of Arbroath © 2015 Scotiana

“I heard the voice of Scotland speak as clearly as it spoke in 1320 :

For so long as one hundred of us remain alive, we will yield in no least way

to the domination of the English.We fight not for glory, nor for wealth, nor for honours, but only and alone

for Freedom, which no good man surrenders but with his life.”

Edinburgh Castle – Enthroned on the Stone of Destiny © 2015 Scotiana

.

Edinburgh Castle – Stone of Destiny© 2015 Scotiana

.

I wish our readers ‘Bonne Lecture’ – Happy Reading! – as you often do, Marie-Agnes, for there is so much to be discovered about Scotland’s Stone of Destiny. (I think you said that the 2008 edition of Mr Hamilton’s work is available as an E-book, which would be very convenient.)

A Bientot, Chers Amis !

Iain.

Mr John Rollo, who hid Scotland’s Stone of Destiny for about 100 days, gave this interview to the BBC in March 1973. The recording was first made public some time after Mr Rollo’s death in December 1985.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9xfaW-VFpg0&t=49s

Iain.

Twenty-five years ago, on St Andrew’s Day 1996, the Stone from Westminster Abbey was returned to Scotland, to be displayed in Edinburgh Castle. Now

there are plans to give it a permanent home in Perth.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-59394186

Earlier in 1996 Mr Campbell Gunn, a respected journalist with the Sunday Post newspaper, had written (7 July): “The stone which rests in London today is unlikely to be the original. .. I was told, by someone involved in the 1950 ‘theft’, where it is. But I promised never to reveal the spot.”

Iain.

Scotiana’s small team join me in sending our kind regards, Mr Hamilton, on the occasion of your Birthday (13 September). Continuing good health and happiness is our wish for you!

Iain.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-politics-63132771

We read with deep sadness on 4 October of the passing of Mr Hamilton. Ian’s health declined. One of his colleagues at the Faculty of Advocates revealed that, distressingly, Ian had lost his eyesight, and that Jeannette, his wife of 50 years, read to him the messages from the cards received just three weeks earlier, on his 97th birthday.

The 2008 Edition of ‘Stone of Destiny’ (available as a Kindle eBook) is dedicated:

“To Jeannette : The safe harbour of all my joys.”

‘She has taught me gentleness, a lesson at which I was never an apt pupil, and against which teaching I sometimes rebel.’ I never did meet Mr Hamilton, but know that I would have liked him very much.

I join the hundreds of thousands, both in Scotland and beyond, who honour and revere his memory. To Jeannette and the family, and all those who loved Ian, we send our kindest thoughts.

Iain.

I was told by a Scotsman (then probably in his 50s) who lived in East Birmingham that he had ‘been involved’ with the taking of the Stone. The conversation would have been around 1982 and I had come to know him through my work at a law centre. He told me that the Stone itself had not been returned to England, merely a replica. I suppose he may have been the friend with whom Kay Matheson had deposited part of the Stone on her journey north. What may be evidence of the truth of what he said is that he had nothing to gain from telling me anything about it at all. I had little idea of what the Stone was or represented at the time and there had been no prior conversation about it. It was a conversation and admission that was so unusual I have never forgotten it.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-64978455

On this day (20 March), 72 years ago, Gavin Vernon and Alan Stuart were ‘taken in’ for questioning by the Glasgow police. “Hearing this, Ian Hamilton went along voluntarily. He was not arrested, nor did he admit to anything.”

What a romantic episode this was! It will never be forgotten.

Iain.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-tayside-central-63130942

Bill Craig and Johnny Josselyn (who helped to recover the Stone from Rochester, Kent) are not named in this brief telling of the story, but there are some more excellent photographs – always interesting to see.

Iain.

The Daily Telegraph newspaper revealed today that Prof. Sir Neil MacCormick, knowing that he was terminally ill, had given to Scotland’s then First Minister, Alex Salmond, a fragment of our Stone of Destiny that had been in his care. (Sir Neil was, of course, son of John MacCormick who had helped to make possible the return of the Stone to Scotland.)

“The final item of the Scottish Cabinet minutes dated Sept 16 2008 was titled ‘The Stone of Destiny’.

“It read: ‘The First Minister said that he had met with Professor Sir Neil MacCormick who had presented him with a fragment of the Stone of Destiny as a personal gift. The permanent secretary agreed that the fragment need not be surrendered to Historic Scotland.’

“Sir Neil was a former special adviser to Mr Salmond and a former SNP MEP. He died in April 2009.”

Iain.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-tayside-central-68625908

The eagerly awaited new Perth Museum will open on Saturday 30 March 2024. It’s at St.John’s Place in the centre of the City (PH1 5SZ), and has been created within the walls of the former City Hall, first constructed in 1909.

Scotland’s Stone of Destiny, the Stone of Scone (Scone is just two miles away), will sit at the centre of many thousands of objects that constitute a Collection of National Significance. Entrance to the new museum is free of charge, but viewing of the Stone of Destiny is by appointment only – very strict security measures are in force. (We can’t have some crazy students taking the precious Stone back to London, can we?)

I shall post a separate Comment, giving a Link to the excellent website of Perth Museum, where details are given of how to book a ‘slot’ to view the Stone.

Iain.

https://perthmuseum.co.uk/the-stone-of-destiny/

No charge is made for admission to the new Perth Museum, or to the separate Stone of Destiny Experience, but generally speaking a booking must be made in advance to see the Stone. Only a small number of 10-minute ‘slots’ are available ‘on the day’. It’s important, too, to attend well in advance of your agreed time slot, to allow security formalities to be completed.

Full details of arrangements to see the Stone of Destiny, including booking, are given at the Perth Museum website, above.

Iain.

Having listened to the BBC’s 1973 John Rollo recording, I wonder if anyone please knows where John Rollo’s co-director, James Scott lived (he who looked after the smaller fragment in a HP carton in his garage before it was reunited with the large portion in Bearsden)? I’m researching the Stone as part of this project: https://thestone.stir.ac.uk/. Thank you!

Professor Sally Foster, University of Stirling, has informed me that she now knows Mr James Scott’s home to have been in Bonnybridge – not too far from John M Rollo’s engineering works, to which Ian Hamilton delivered, under cover of darkness, the larger portion of the Stone. It was put into a sturdy wooden packing-case before being concealed behind some panelling, even the fixing nails being treated with corrosive material to give the impression of age.

Mr Scott seems to have been a Director of the firm, sharing its management with Mr Rollo, and it appears that he played some part in concealing the smaller part of the Stone, which arrived at Bonnybridge a few days later and was put into a solid pasteboard carton that had originally held bottles of HP Sauce. (There’s a certain irony here – the Houses of Parliament, which inspired the Sauce, convene in the Palace of Westminster, while Scotland’s Stone of Destiny was repatriated from Westminster Abbey, so close by.)

Ian Hamilton and his young friends considered their task over, once they had delivered both parts of the Stone safely to Bertie Gray and John MacCormick. The smaller part does seem to have been moved several times however, to avoid discovery, and of this Ian had no precise knowledge. He did write words to the effect that, if someone’s Grandfather, or someone else’s Uncle Bob had allegedly helped to hide the Stone, that might well be true!

It seems beyond doubt that it was in Mr Willie White’s garage, at his home in Bearsden, that the Stone was expertly repaired before being returned.

Iain.

While it’s a romantic notion to write (as I did) that King Edward had taken by force in 1296 the Stone “upon which Scottish kings had been crowned for more than four centuries” – and although little more of the events of these ancient times is likely now to be discovered – we should aim to separate where possible, I think, the true history of the Stone from the many legends that have gathered around it.

The original Stone of legend, the Lia Fail (=Stone of Fate, Stone of Destiny) was of black basalt, quite distinct from the pink/red sandstone of Scone, and must have been of considerable size, for it is believed to have been fashioned into the shape of a rounded seat or chair. The Lia Fail was hidden from Edward’s soldiers in 1296. They carried off to England a simple block of sandstone, while the precious old Stone is still thought to lie buried (and lost) on Bonhard Hill, Scone.

Campbell Gunn, the Sunday Post journalist, wrote in his short piece (July 1996) of the comic song, ‘The Wee Magic Stane’ (by Johnny McEvoy, I think. I’d love to learn more of Mr McEvoy, who seems to have emigrated to Canada in the 1950’s.) Much of the humour of this song comes from the idea that, such was the demand for replicas of Scotland’s Stone of Destiny after its repatriation in 1951, that copies were mass-produced; so many were made, in fact, that the ‘original’ Stone was mixed up with all the others!

I mentioned that Ian Hamilton had seen at Bertie Gray’s yard, Lambhill, a replica Stone ‘made in connection with an earlier plot, one that did not come off’. (Compton Mackenzie was involved in this plan for a ‘daylight raid’, I think.) Bertie Gray seems to have made at least one more replica of the Stone around 1951, and possibly two more copies.

One Stone found its way to the Arlington Bar in Woodlands Road, Glasgow (close to the University), where it was displayed in a glass case. A second – it is claimed – was substituted for the Westminster Stone and surrendered at Arbroath Abbey. (Ian Hamilton would dispute this; he has written emphatically that the Stone returned at Arbroath was the Stone that he and his young friends brought north.)

The true Westminster Stone, it is alleged, was then hidden at various places in Scotland. In 1972, it was known to have been concealed at St. Columba’s Church, Dundee, whose minister, Rev. John Mackay Nimmo was a friend of Bertie Gray and a fellow member of the Knights Templar (allied to the Freemasons, I think). When St. Columba’s closed, the Stone was moved for safe-keeping to ‘a Scottish castle’, and by 30 November 1989 (St. Andrew’s Day) it had turned up at the Old Glasgow Museum, Glasgow Green (the ‘People’s Palace).

Whatever the truth regarding these copies of the Stone, the controversies around them served to keep alive the question of permanently repatriating the Stone of Destiny to Scotland.

Michael Forsyth, now Lord Forsyth, Conservative (and Unionist) Secretary of State for Scotland in 1996, declared himself satisfied that the Stone restored to Scotland that year (and now at Perth) was the original from 1296. Ian Hamilton was gracious, and wise too, I think. ‘I have no reason to think that Mr. Forsyth loves Scotland any less than I do,’ he wrote.

Iain.