Dear readers,

Here we are again, at the beginning of a new year, hoping for the best in the coming months. Given the sanitary situation we still don’t know when we will be allowed to return to Scotland. En attendant des jours meilleurs I try to compensate my frustrations by browsing our pictures of Scotland, reading or re-reading books about Scotland and by my favourite Scottish authors! Walter Scott is one of my favourites as you may already have learned in my previous posts 😉 In 2007, during one of our unforgettable visits at Abbotsford, Janice and I promised to read all the books written by Sir Walter. C’était un peu fou…given the number of books the great Scottish writer did wrote! Last year, to celebrate the author’s 250th birthday anniversary I renewed my promise to the Master of Abbotsford. In my last post about Sir Walter, I wrote:

Next time I will introduce The Black Dwarf, the first story contained in the 1st series of Tales of My Landlord . Tales of my Landlord is a series of novels by Sir Walter Scott. It forms a subset of the so-called ‘Waverley Novels’. There are four series of stories.

Here I am, today, in front of my white page… hoping to give you a good idea of The Black Dwarf and to inspire you to read or re-read it.

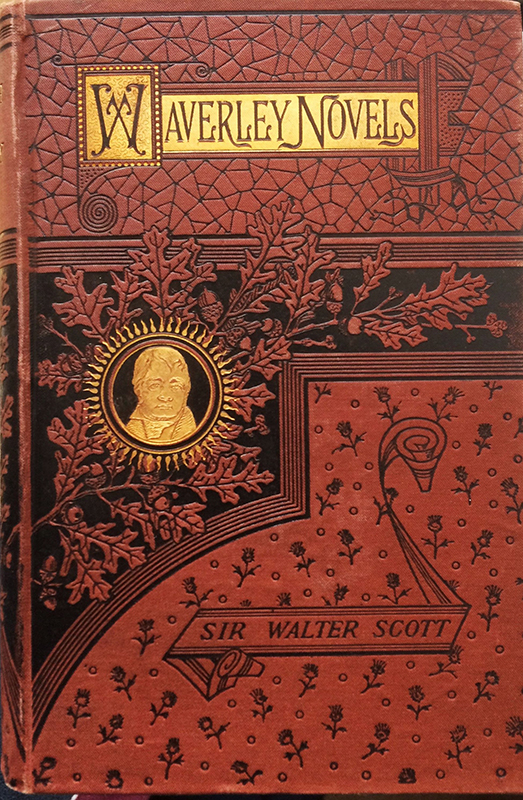

The Waverley Novels by Sir Walter Scott – ancient volume

The Black Dwarf is the 4th novel written by Sir Walter Scott and also the fourth volume I’ve read on the way to my promise… there is still a long way to go! 😉

The first three novels were intended to be a trilogy focusing on recent* Scottish history and traditions: Waverley → 1745… Guy Mannering → 1783… The Antiquary → 1794

*recent for Sir Walter 😉 (1771-1832)

- Waverley (1814)

- Guy Mannering (1815)

- The Antiquary (1816)

Contents of Tales of My Landlord series by Sir Walter Scott

The Black Dwarf is the first novel appearing in 1816, together with Old Mortality, in the first of the four series entitled “Tales of My Landlord”. Initially, the Tales should have been composed of a single series including no more than four novels of one volume each and intended to focus on more ancient times than the previous three novels. Finally, there would be four series in the Tales and the dates of the stories would spread out over a long period of time from 1097 (Count Robert of Paris ) to 1736 (The Heart of Midlothian). The only novel of this series to be set abroad is Count Robert of Paris which, as its name doesn’t indicate, takes place in Constantinople and not in Paris!

The first series of the Tales finally contained only two books with one volume for The Black Dwarf and three volumes for Old Mortality.

Sir Walter Scott’s desk Abbotsford Scotiana 2001

Sir Walter’s impalpable presence can be felt in everywhere in Abbotsford,

when the mythical place is not invaded by crowds of visitors…

In 2000, we were lucky to be invited by Dame Jean Maxwell-Scott

to stay after closing time! It was so kind of her !

Abbotsford Sir Walter’s desk © 2015 Scotiana

Sir Walter was a very prolific author. I’m very impressed to see the number of books he wrote while he had so many other activities: his work as Sheriff-Depute of the County of Selkirk (since 1799), his busy family and social life and, last but not least, the building of his house at Abbotsford which took about ten years to build and to the construction of which he contributed quite a lot.

I’ve read Sir Walter used to write from 5 a.m. to 12 a.m. each day, with one or two of his favourite dogs for company…

Painting by Sir Francis Grant of “Sir Walter Scott in his study at Abbotsford writing his last novel ‘Count Robert of Paris’ “, 1831

and sometimes with his cat. 😉

Sir Walter Scott in his Study at Castle Street by Sir John Watson Gordon – 1810

The action of The Black Dwarf takes place in 1708, in the Scottish Borders, against the background of the first uprising to be attempted by the Jacobites after the Act of Union (1707). The Act took effet on 1 May 1707. On this date, the Scottish Parliament and the English Parliament united to form the Parliament of Great Britain, based in the Palace of Westminster in London, the home of the English Parliament. Hence, the Acts are referred to as the Union of the Parliaments.

Abbotsford © 2007 Scotiana

Illustration of Elshie from The Black Dwarf by Sir Walter Scott

THE BLACK DWARF:

Walter Scott’s first three novels had been published anonymously or by the author of Waverley. The new series was published under the strange name of Jedediah Cleishbotham who was supposed to be a schoolmaster and parish clerk. This funny pen name is composed of a Puritan Christian name and a surname consisting of the Scots dialect ‘cleish’ [to whip], and ‘bottom’. A whole book could be devoted to the story of this new series and the role played by that Jedediah Cleishbotham…

A new publisher for a new series…

Waverley, Guy de Mannering or the Astrologer, The Antiquary had been published by Archibald Constable* but, trying to secure better conditions, Walter Scott entrusted his friend and printer, James Ballantyne**, with the task of initiating secret negotiations with another publisher, William Blackwood*** (Edinburgh) who was associated with John Murray (London).

(…) “Scott instructed James Ballantyne to open confidential negotiations with William Blackwood. James solemnly began by pledging the bookseller to breathe not a syllable of his proposal to anyone but John Murray. He was empowered to offer them the publication of a work of fiction, like Waverley, of which he was not at liberty to give either the title or the author’s name.”

For a lively and detailed description of the many tractations which took place between Sir Walter Scott and his publishers, and especially at the time of the publication of “Tales of My Landlord”, I advise you to read the remarkable biography published in 1970 by Edgar Johnson Sir Walter Scott The Great Unknown (1st volume page 547 in the chapter “Is Not the Truth the Truth” ). For the fans of Sir Walter the two volumes of this biography contain 1400 pages… a literary bible!

Who’s who in Sir Walter Scott’s entourage…

Lithograph of Archibald Constable from A History of Booksellers, the Old and the New.

* In 1805, Archibald Constable published, in conjunction with Longman & Co. of London, the first original work of Sir Walter Scott, “The Lay of the Last Minstrel,” the success of which was also far beyond his expectations. In the ensuing year, he issued a beautiful edition of what he termed “The Works of Walter Scott, Esq.,” in five volumes, comprising the poem just mentioned, the Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, Sir Tristrem, and a series of Lyrical Pieces. Notwithstanding the success of the “Lay of the Last Minstrel,” Mr Constable was looked upon as a bold man when, in 1807, he offered Mr Scott one thousand pounds for a poem which was afterwards entitled “Marmion.” Such munificence was quite a novelty in the publishing trade of Scotland, and excited some attention even in a part of the island where literary affairs had heretofore been conducted on a larger scale. Not long after the appearance of this poetical romance, Mr Constable and his partner had a serious difference with its illustrious author, which lasted till 1813, although in the interval he edited for them the works of Swift, as he had previously those of Dryden.

(…) Mr Constable and his partner published after 1813, all the poetical works of Sir Walter Scott, and the whole of his prose fictions (excepting the first series of the Tales of My Landlord) down to the year 1826

(From “Significant Scots : Archibald Constable” Source : Electric Scotland)

Scottish publisher James Ballantyne (1772–1833)

** James Ballantyne (1772–1833) was a Scottish solicitor, printer, editor and publisher who worked for his friend Sir Walter Scott.

Portrait of William Blackwood by William Allan 1830

*** William Blackwood was Scotland’s most successful publisher in the early nineteenth century. He was born in Edinburgh and at the age of fourteen began a six year apprenticeship to the booksellers Bell & Bradfute. Following further training in Glasgow and London, he opened his first shop on Edinburgh. Specialising in selling rare books the business was a success. In 1813 Blackwood became the agent for the printers of Sir Walter Scott’s novels

A detailed and very useful analysis of The Black Dwarf (composition and sources – editions – plot introduction – plot summary – characters – chapter summary – reception – references – external links) is to be found here, on Wikipedia.

As Hobbie Elliot was returning over a wild moor from a day’s sport, thinking of the legends he had heard of its supernatural occupants after nightfall, he was overtaken by Patrick Earnscliff, whose father had been killed in a quarrel with the laird of Ellieslaw, Richard Vere. The moon suddenly revealed the figure of a human dwarf, who, on being spoken to, expressed severe misanthropy, refused their offers of assistance, and bid them begone. Hobbie invited Earnscliff to sup with his womenfolks, and pass the night at his farm, and then accompanied him next morning to confront the strange being by daylight. They collected some stones for him for constructing a hut. In later days Earnscliff supplied him with food and other necessaries. In a short time he had completed his dwelling, and became known to the neighbours, for whose ailments he prescribed, as Elshender the Recluse.

Being visited by Isabella Vere and two of her cousins/friends, he told their fortunes, and he gave Isabella a rose, with strict injunctions to bring it to him in her hour of adversity. As they rode homewards, the one cousin’s conversation implied that Isabella could love young Patrick Earnscliff. Isabella denied that was possible. And her father Mr. Vere intended her to marry Sir Frederick Langley, whom she and her cousins hated. Another of the dwarf’s visitors was Willie Graeme of Westburnflat, on his way to avenge an affront he had received from Hobbie Elliot. The next day Hobbie’s hunting dog killed one of the dwarf’s goats, angering the dwarf and he declared that retribution was at hand.

Shortly afterwards, Willie Graeme brought word that he and his companions had fired Hobbie’s farm, and carried off his sweetheart, Grace Armstrong, and some cattle. On hearing this Elshie insisted that Grace should be given up uninjured and wrote out a money order to persuade them to release her and dispatched Willie Graeme to do it. Hobbie, having dispersed his neighbours in search of Grace and his cattle, went to consult Elshie, who handed him a bag of gold, which he declined, and intimated that he must seek her whom he had lost “in the west.” Earnscliff and his party had tracked the cattle as far as the English border, but on finding a large English force assembling there they returned, and it was decided to attack Westburnflat’s stronghold. On approaching it, a female hand, which her lover swore was Grace’s, waved a signal to them from a turret, and as they were preparing a bonfire to force the door, Graeme agreed to release his prisoner, who proved to be Isabella Vere. On reaching home, however, Elliot found that Grace had been brought back, and at dawn he started off to accept the money which the dwarf had offered him to repair his homestead.

Isabel had been seized by ruffians while walking with her father, who appeared overcome with grief, declared that Earnscliff was the offender and led searches in all directions except south. The second day Mr. Vere’s cousin Ralph Mareschal insisted that they search to the south. Mr Vere’s suspicion seemed justified by their soon meeting his daughter returning under Earnscliff’s care; but she confirmed his version of the circumstances under which he had intervened, to the evident discomfiture of her father and Sir Frederick.

The Black Dwarf – Chapel scene illustration

At a large gathering, the same day, of the Pretender’s adherents in the hall of Ellieslaw Castle, Ralph Mareschal prompted everyone to swear fidelity to supporting James VIII, the Old Pretender’s cause. After that, to Mr. Vere and Sir Frederick, he produced a letter telling news that the Old Pretender’s ships had been turned back. To continue, Sir Frederick insisted that his marriage with Isabella should take place before midnight. She consented, on her father’s representation that his life would be forfeited if she refused, when Mr Ratcliffe, conservator of her father’s bankrupt estate, persuaded her to make use of the token which Elshie had given her, and escorted her to his dwelling. Elshie told her to return home, and that he would come to prevent the marriage. Just as the ceremony was commencing in the chapel, a voice, which seemed to proceed from her mother’s tomb, uttered the word “Forbear.” The dwarf’s real name and rank were then revealed, as well as the circumstances under which he had acquired the power of thus interfering on Isabella’s behalf, while Hobbie and his friends supported Mr Ratcliffe in dispersing the would-be rebels.

The next morning Isabella learned that her father had fled, and was already halfway to the coast to flee the country. He had refused an offer of allowance from Ratcliffe, instead to rely on his daughter. The dwarf, Sir Edward, at the same time disappeared from the neighbourhood. All the Ellieslaw property, as well as the baronet’s, was settled on Isabella, who soon married Earnscliff. The last chapter told the fates of the major characters.

Reception of the book

If The Black Dwarf is not one of the most famous novels written by Sir Walter Scott and it proved to be much less popular than Old Mortality, it is nevertheless quite interesting. At first, when he discovered it, William Blackwood to whom the manuscript had been entrusted was very enthusiastic:

“Its first 192 pages threw William Blackwood* into such a fever of enthusiasm when he was allowed to read themthat he was unable to sleep. Before going to bed, he wrote Murray nine quarto pages of rhapsodic comment. ‘There cannot be a doubt as to the splendid merit of the work…’ Exuberantly, a week later, he embarked for London, simmering with excitement about our book.” (Sir Walter Scott The Great Unknown – volume I 1771-1821 – Edgar Johnson Hamish Hamilton Ltd 1970)

However, some time later he admits to have been very disappointed by the last part of the novel and even suggested a few modifications to its author. 😉

“But when he read the later chapters he was not quite so happy. The story that had begun so splendidly, he felt, limped to but a feeble ending. William Gifford*, to whom Murray showed the book agreed. When Blackwood returned to Edinburgh he learned that Ballantyne** too had shared their disappointment. Never one to beat around the bush, he told the printer bluntly that he thought the conclusion should be changed and even ventured to outline what struck him, as a better resolution of the plot. Worried for both his own investment and the author’s fame, he would be willing himself, he stated, to pay for reprinting the canceled sheets. James passed these proposals on to Scott.” (Sir Walter Scott The Great Unknown)

* William Gifford (April 1756 – 31 December 1826) was an English critic, editor and poet, famous as a satirist and controversialist.

Sir Walter’s flash of anger 😉

Sir Walter was very angry when he learned when he learned how his manuscript had been criticized and he didn’t change anything to his text, preferring to spend his time finishing the last volume of Old Mortality. Later, he regretted his words and even admitted (not without humour) that he had botched the conclusion of The Black Dwarf.

“His temper shot like a rocket. ‘My respects to the Booksellers,’ he fired back, ‘& I belong to the Death-head Hussars of literature who neither take nor give criticism. I know no business they had to show my work to Gifford nor would I cancela leaf to please all the critics of Edinburgh & London… I never heard of such impudence in my life. Do they think I dont know when I a writing ill as well as Gifford can tell me… I beg there may be no more communications with critics. These born idiots do not know the mischief they do to me & themselves. I DO by God.”

The Black Dwarf, to be sure, although he had refused to alter it at Blackwood’s behest, was, he agreed “wishy-washy enough”. He had begun it well , “but tired of the ground I had trode so often,” he confessed to Lady Louisa Stuart. “So I quarelled with my story & bungled up a conclusion as a boarding school Miss finishes a task which she had commenced with great glee & accuracy. But Old Mortality, he thought, was “the best I have yet been able to execute.” (Sir Walter Scott Edgard Johnson)

Great that Old Mortality be the next book on my reading list !!! 😉

FINALLY, when The Black Dwarf was published the book was well received by the public and it is still today by the readers of Sir Walter Scott. Personally, I really took much pleasure in reading and still more in re-reading it.

A VERY ATMOSPHERIC SETTING: full of invisible presences – folk Tales – legends – superstitions…

As soon as the first pages, the reader is immersed in a mysterious and rather unsetlling atmosphere. The landscape is described as wild and solitary, rather gloomy, exactly the kind of place where one expects to meet strange creatures and where one can take the smallest rock for a monster… indeed, it’s exactly what happens with the apparition of the frightening figure of The Black Dwarf .

The object which alarmed the young farmer in the middle of his valorous protestations, startled for a moment even his less prejudiced companion. The moon, which had arisen during their conversation, was, in the phrase of that country, wading or struggling with clouds, and shed only a doubtful and occasional light. By one of her beams, which streamed upon the great granite column to which they now approached, they discovered a form, apparently human, but of a size much less than ordinary, which moved slowly among the large grey stones, not like a person intending to journey onward, but with the slow, irregular, flitting movement of a being who hovers around some spot of melancholy recollection, uttering also, from time to time, a sort of indistinct muttering sound. This so much resembled his idea of the motions of an apparition, that Hobbie Elliot, making a dead pause, while his hair erected itself upon his scalp, whispered to his companion, “It’s Auld Ailie hersell! Shall I gie her a shot, in the name of God?”

“For Heaven’s sake, no,” said his companion, holding down the weapon which he was about to raise to the aim—“for Heaven’s sake, no; it’s some poor distracted creature.”

(The Black Dwarf)

There is something of a gothic tale in The Black Dwarf and the story is also a kind of edifying tale, the main protagonist being torn between his desire for revenge against the men who behave so badly to him and his natural goodness which led him to do good to people worth of it. By force of circumstance the “black dwarf” became a surly, gruff loner, a solitary shunning the human race but loving nature and animals. I like this character. In some way, Sir Walter’s fictional character rehabilitates the real dwarf whom Sir Walter had once met.

The cleugh, or wild ravine, into which Hobbie Elliot had followed the game, was already far behind him, and he was considerably advanced on his return homeward, when the night began to close upon him. This would have been a circumstance of great indifference to the experienced sportsman, who could have walked blindfold over every inch of his native heaths, had it not happened near a spot, which, according to the traditions of the country, was in extremely bad fame, as haunted by supernatural appearances. To tales of this kind Hobbie had, from his childhood, lent an attentive ear; and as no part of the country afforded such a variety of legends, so no man was more deeply read in their fearful lore than Hobbie of the Heugh-foot; for so our gallant was called, to distinguish him from a round dozen of Elliots who bore the same Christian name. It cost him no efforts, therefore, to call to memory the terrific incidents connected with the extensive waste upon which he was now entering. In fact, they presented themselves with a readiness which he felt to be somewhat dismaying.

This dreary common was called Mucklestane-Moor, from a huge column of unhewn granite, which raised its massy head on a knell near the centre of the heath, perhaps to tell of the mighty dead who slept beneath, or to preserve the memory of some bloody skirmish. The real cause of its existence had, however, passed away; and tradition, which is as frequently an inventor of fiction as a preserver of truth, had supplied its place with a supplementary legend of her own, which now came full upon Hobbie’s memory. The ground about the pillar was strewed, or rather encumbered, with many large fragments of stone of the same consistence with the column, which, from their appearance as they lay scattered on the waste, were popularly called the Grey Geese of Mucklestane-Moor. The legend accounted for this name and appearance by the catastrophe of a noted and most formidable witch who frequented these hills in former days, causing the ewes to KEB, and the kine to cast their calves, and performing all the feats of mischief ascribed to these evil beings. On this moor she used to hold her revels with her sister hags; and rings were still pointed out on which no grass nor heath ever grew, the turf being, as it were, calcined by the scorching hoofs of their diabolical partners.

(The Black Dwarf)

GEOGRAPHICAL SETTING: a region well-known by the author

Scottish Borders Sign & Cattle grid © 2012 Scotiana

The story is set in the Liddesdale hills which are situated in the Scottish Borders, a place familiar to Scott after the time he spent there to collect ballads for his Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border.

Scottish Borders solitary landscape © 2012 Scotiana

We travelled through the wild and wintry landscape of the Scottish Borders in September 2012, after our visit at the native place, museum, grave and superb Memorial to MacDiarmid near Langholm… I have got into the habit of taking pictures of all the rowans I fall upon when travelling in Scotland.. those beautiful trees with their red berries, le sorbier des oiseaux, a favourite tree of the Black Dwarf…

Engraving of Hermitage Castle in 1814

we also visited Hermitage Castle which is situated not far, a favourite place of Sir Walter, located on the banks of the Liddel…

Portrait of Sir Walter Scott by Sir Henry Raeburns1809

A HISTORICAL NOVEL ?

The Black Dwarf is not à proprement parler a “historical novel” such as Waverley, to mention only this one, but its historical setting is essential in this story.

“It is enough for our purpose to say, that all Scotland was indignant at the terms on which their legislature had surrendered their national independence. The general resentment led to the strangest leagues and to the wildest plans. The Cameronians were about to take arms for the restoration of the house of Stewart, whom they regarded, with justice, as their oppressors; and the intrigues of the period presented the strange picture of papists, prelatists, and presbyterians, caballing among themselves against the English government, out of a common feeling that their country had been treated with injustice. The fermentation was universal; and, as the population of Scotland had been generally trained to arms, under the act of security, they were not indifferently prepared for war, and waited but the declaration of some of the nobility to break out into open hostility. It was at this period of public confusion that our story opens”.

(The Black Dwarf)

Below are a few historical reminders (from Magnus Magnusson : Scotland the Story of a Nation – Harper Collins 2000).

Magnus Magnussons introduces each of his chapters with a quote from Sir Walter Scott’s Tales of a Grandfather* (1828-1830).

*In May 1827, Scott came up with the idea of writing the History of Scotland addressed to his six-year-old grandchild, John Hugh Lockhart. The project was partly inspired by the success of John Wilson Croker’s Stories for Children Selected from the History of England.

- 1688: Birth of James Stuart, the ‘Old Pretender’; William of Orange lands in England. Beginning of the ‘Glorious Revolution’; James VII and II flees to France

- 1689: William and Mary crowned in England; ‘Bonnie Dundee’ wins Battle of Killiecrankie but is killed; Battle of Dunkeld

- 1690: James VII and II defeated at the Battle of the Boyne

- 1692: Massacre of Glencoe

- 1694: death of Queen Mary

- 1698-1700: The Darien expedition

- 1701: Death of James VII and II in exile

- 1702: Death of King William eight years after his wife, Queen Mary. Accession of Queen Anne

- 1704 : Scotland’s parliament passes the Act of Security

- 1705: England’s Parliament passes the Alien Act

- 1707: Union Act passed

- 1708: First Jacobite Rising fails

- 1714: Death of Queen Anne 28 December – George I succees

- 1715: The 1715 Rising; Battle of Sherifmuir

- 1719: The 1719 Rising: Battle of Glenshiel

- 1720: Birth of Charles Edward Stuart, ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’…

- 1745: Prince Charles lands in Scotland; the ’45’ Rising; Battle of Prestonpans; the march to Derby, and the retreat

- 1746 Battle of Falkirk Muir; Battle of Culloden; Prince Charles escapes to France

- 1746-82: Act of Prescription bans Highland dress and language

- 1771: Birth of Walter Scott

- 1789: French Revolution

- 1802: The Minstrelsy of the Border

A MORAL TALE

Au fil des pages the misanthrope becomes a philanthropist and thanks to him le bien triomphe du mal at the end of the novel…

WHO HIDES BEHIND THE CHARACTER OF “THE BLACK DWARF” ?

Memorial stone of David Ritchie at Manor Kirkyard © Copyright James Denham – Geograph

A mysterious dwarf whom Sir Walter had met…

(…) Our purpose was to see the former home of one of the strangest human beings who ever lived; one who found the seclusion of the beautiful vale well adapted to shield him from the unwelcome observation of the curious-minded. David Ritchie, or ‘Bow’d Davie o’ the Wud’use (Or Bowed Davie of the Woodhouse Farm.) as he was called, was for many years a familiar figure to the few farmers of the valley.

FROM WALTER SCOTT’S INTRODUCTION TO THE BLACK DWARF (1830 edition)

“The personal description of Elshender of Mucklestane-Moor has been generally allowed to be a tolerably exact and unexaggerated portrait of David of Manor Water.”

“The ideal being who is here presented as residing in solitude, and haunted by a consciousness of his own deformity, and a suspicion of his being generally subjected to the scorn of his fellow-men, is not altogether imaginary. An individual existed many years since, under the author’s observation, which suggested such a character. This poor unfortunate man’s name was David Ritchie, a native of Tweeddale. He was the son of a labourer in the slate-quarries of Stobo, and must have been born in the misshapen form which he exhibited, though he sometimes imputed it to ill-usage when in infancy. He was bred a brush-maker at Edinburgh, and had wandered to several places, working at his trade, from all which he was chased by the disagreeable attention which his hideous singularity of form and face attracted wherever he came. The author understood him to say he had even been in Dublin.

Tired at length of being the object of shouts, laughter, and derision, David Ritchie resolved, like a deer hunted from the herd, to retreat to some wilderness, where he might have the least possible communication with the world which scoffed at him. He settled himself, with this view, upon a patch of wild moorland at the bottom of a bank on the farm of Woodhouse, in the sequestered vale of the small river Manor, in Peeblesshire. The few people who had occasion to pass that way were much surprised, and some superstitious persons a little alarmed, to see so strange a figure as Bow’d Davie (i.e. Crooked David) employed in a task, for which he seemed so totally unfit, as that of erecting a house. The cottage which he built was extremely small, but the walls, as well as those of a little garden that surrounded it, were constructed with an ambitious degree of solidity, being composed of layers of large stones and turf; and some of the corner stones were so weighty, as to puzzle the spectators how such a person as the architect could possibly have raised them. In fact, David received from passengers, or those who came attracted by curiosity, a good deal of assistance; and as no one knew how much aid had been given by others, the wonder of each individual remained undiminished.

The proprietor of the ground, the late Sir James Naesmith, baronet, chanced to pass this singular dwelling, which, having been placed there without right or leave asked or given, formed an exact parallel with Falstaff’s simile of a “fair house built on another’s ground;” so that poor David might have lost his edifice by mistaking the property where he had erected it. Of course, the proprietor entertained no idea of exacting such a forfeiture, but readily sanctioned the harmless encroachment.

The personal description of Elshender of Mucklestane-Moor has been generally allowed to be a tolerably exact and unexaggerated portrait of David of Manor Water.”

Driven into solitude, he became an admirer of the beauties of nature. His garden, which he sedulously cultivated, and from a piece of wild moorland made a very productive spot, was his pride and his delight; but he was also an admirer of more natural beauty: the soft sweep of the green hill, the bubbling of a clear fountain, or the complexities of a wild thicket, were scenes on which he often gazed for hours, and, as he said, with inexpressible delight. It was perhaps for this reason that he was fond of Shenstone’s pastorals, and some parts of PARADISE LOST. The author has heard his most unmusical voice repeat the celebrated description of Paradise, which he seemed fully to appreciate. His other studies were of a different cast, chiefly polemical. He never went to the parish church, and was therefore suspected of entertaining heterodox opinions, though his objection was probably to the concourse of spectators, to whom he must have exposed his unseemly deformity. He spoke of a future state with intense feeling, and even with tears. He expressed disgust at the idea, of his remains being mixed with the common rubbish, as he called it, of the churchyard, and selected with his usual taste a beautiful and wild spot in the glen where he had his hermitage, in which to take his last repose. He changed his mind, however, and was finally interred in the common burial-ground of Manor parish.

We have stated that David Ritchie loved objects of natural beauty. His only living favourites were a dog and a cat, to which he was particularly attached, and his bees, which he treated with great care. He took a sister, latterly, to live in a hut adjacent to his own, but he did not permit her to enter it. She was weak in intellect, but not deformed in person; simple, or rather silly, but not, like her brother, sullen or bizarre. David was never affectionate to her; it was not in his nature; but he endured her. He maintained himself and her by the sale of the product of their garden and bee-hives; and, latterly, they had a small allowance from the parish. Indeed, in the simple and patriarchal state in which the country then was, persons in the situation of David and his sister were sure to be supported.

BROWSING MY LIBRARY

The Country of Sir Walter Scott

Charles S. Olcott The Country of Sir Walter Scott Cassell edition 1913

Of course, Charles Olcott’s book “The Country of Sir Walter Scott”, is open on my desk at chapter XI “The Black Dwarf”..

Late in the afternoon of a beautiful May day, while on one of our drives from Melrose, we turned off the main road a few miles west of Peebles, and, crossing the Tweed, entered the vale of Manor Water. This secluded valley, peaceful and charming, would make an ideal retreat for any one who wished to escape the noise and confusion of a busy world. The distinguished philosopher and historian, Dr. Adam Ferguson, found it so, when in old age he took up his residence at Hallyards, where his young friend, Walter Scott, paid him a visit in the memorable summer of 1797.

It was not a desire to retire from worldly activities, however, or to visit the house of Dr. Ferguson, that led us into the quiet valley. Our purpose was to see the former home of one of the strangest human beings who ever lived; one who found the seclusion of the beautiful vale well adapted to shield him from the unwelcome observation of the curious-minded. David Ritchie, or ‘Bow’d Davie o’ the Wud’use (Or Bowed Davie of the Woodhouse Farm.) as he was called, was for many years a familiar figure to the few farmers of the valley. He was born about 1735, and lived to be seventy-six years of age. (…) His shoulders were broad and muscular, and his arms unusually long and powerful, though he could not lift them higher than his breast. But Nature seemed to have omitted providing him with legs and thighs. The upper part of his body, with proportions seemingly intended for a giant, was set upon short fin-like legs, so small that when he stood erect they were almost invisible. His height was scarcely three feet and a half.

(…) His mind corresponded in deformity with his body. He was eccentric, irritable, jealous, and strangely superstitious. He was sensitive beyond all reason and could not endure even the glance of his curious fellow men. He read insult and scorn in faces where neither was intended. He thoroughly despised all children and most strangers. His whole nature seemed to have been poisoned with bitterness of spirit because he was not like other men. Scott was introduced to this singular individual by Dr. Ferguson, who had taken a great interest in him. Nineteen years later, and five years after the death of David Ritchie, he made the recluse of Manor Valley known to the world as ‘The Black Dwarf,’ in the first of the ‘Tales of My Landlord.’

The Black Dwarf’s Cottage from The Country of Sir Walter Scott Charles Olcott 1913

Black Dwarf’s Cottage painting John Blair 1893

I’ve found a picture of David Ritchie’s house which he had built himself and where he lived with his sister… I would have liked to find a picture of his garden… with the rowans he had planted to protect his house from evil spirits… makes me think we should plant one or two of these beautiful trees in front on our new house in Périgord Noir.

Sir Walter Scott The Great Unknown by Edgar Johnson– Hamish Hamilton 1970

This book is a literary gem for Sir Walter’s fans!

I have two copies of this book… the first one being underlined and covered with my notes I’ve bought a second one to put it on Sir Walter’s shelf in my library ;-). It’s a great book. I have also the first of the two volumes of La Pléiade dedicated to Sir Walter Scott. It contains Waverley translated by Henri Suhamy 😉 How I would have liked to follow the author’s lectures at the University where he used to teach!

Scott-Land by Stuart Kelly

Scott-Land Stuart Kelly Polygon 2010 edition

Stuart Kelly’s book reveals Scott the paradox: the celebrity unknown, the nationalist unionist, the aristocrat loved by communists, the forward-looking reactionary. Part literary study, part surreptitious autobiography, Scott-Land unveils a complex, contradictory

There are twenty-five roads called Waverley in Britain. Sir Walter Scott appears on all the baknotes of the Bank of Scotland. He inspired Byron, Dumas, Pushkin, Tolstoy, Manzoni, Balzac and Buchan, and was loathed by Twain, Zola, Joyce and MacDiarmid. The biggest monument to an author on the planet is devoted to Scott, and hardly anyone reads his books.

No writer has ever been as famous as sir Walter Scott once was; and no writer has ever enjoyed such huge acclaim followed by such absolute neglect and outright hostility. But Scotland would not be Scotland except for Scott. All the icons of Scottishness have their roots in Scott’s novels, poems, public events and histories. It’s a legacy both inspiring and constraining, and just one of the ironies that fuse Scott and Scotland into Scott-Land.

(From the back cover of Stuart Kelly’s Scott-Land)

I have many more books about Sir Walter in my library but I think this post is already quite long to list more of them, so I will tell you more about my books in the next posts…

I hope to have made you want to read The Black Dwarf. 😉

Bonne lecture !

Á bientôt. Mairiuna

TWO BONUSES 😉

First just have a look at this extraordinary You Tube video created by Mark Nicol in 2017… “The Legend of the Black Dwarf”… I’ve watched it several times because, being French, it’s rather difficult for me to understand Mark’s language. However, I think I’ve understood the essential. I do love the music and the Scottish atmosphere I enjoy so much when walking amidst solitary landscapes and wintry moor… waouh ! Tolkien’s hobbits are also evoked 😉 Many thanks Mark! Now, I’m looking forward to following The Black Dwarf trail… and also to go back to Abbotsford 😉

Sir Walter Scott The Great Unknown by Edgar Johnson (two volumes)

“Love your history of the borders, thanks for that one,I remember reading somewhere about a dwarf who lived near Peebles, local kids use to throw stones at him, think he was killed and it said he was buried at the crossroads, as they did with witches ect, sure it showed you his grave at the crossroads and it was marked, think it must have been in the archaeological magazine back in the sixties, someone must have had knowledge of the dwarf, poor man, wish I had kept these magazines now, I was a member back then, I also remember reading in it, the duke of buccleuch was told where to mark his boundary up the moor at Hawick, but he took another mile before marking it, wish I could get my hands on some of these old archaeological magazines now.”

(You Tube comment written by Isobel Chapman)

Isobel wrote this comment four years ago. Perhaps she has since found her old archaeological magazines 😉

Last but not least, here’s a bit of Scottish history… 1707… the Act of Union… The Black Dwarf Story takes place about this time… the jacobite first rebellions…

Leave a Reply