The first time I heard about St Kilda islands was during a conference on Scotland given by Serge Oliéro on 17 January 2000. It was only a few months before our first Scottish journey. Serge Oliéro is the author of Terre d’Écosse which he dedicated to me with these words “Pour Marie-Agnès Bon voyage chez les Celtes”.

None of us could have imagined then that our first voyage in spring 2000 would be only the beginning of a wonderful Scottish adventure which has never ceased to go on since…

Gleann Mor on St Kilda on a sunny August day 2019 – Wikipedia

We’ve visited a number of Scottish islands: the Inner Hebrides including Islay, Jura, Mull, Iona, Staffa, Skye and the Outer Hebrides from Lewis in the North to Vatersay in the South, Handa island on the north of the western coast of Scotland and Orkney but we’re always dreaming to go to St Kilda, to the Shetland islands, to Fair Isle…

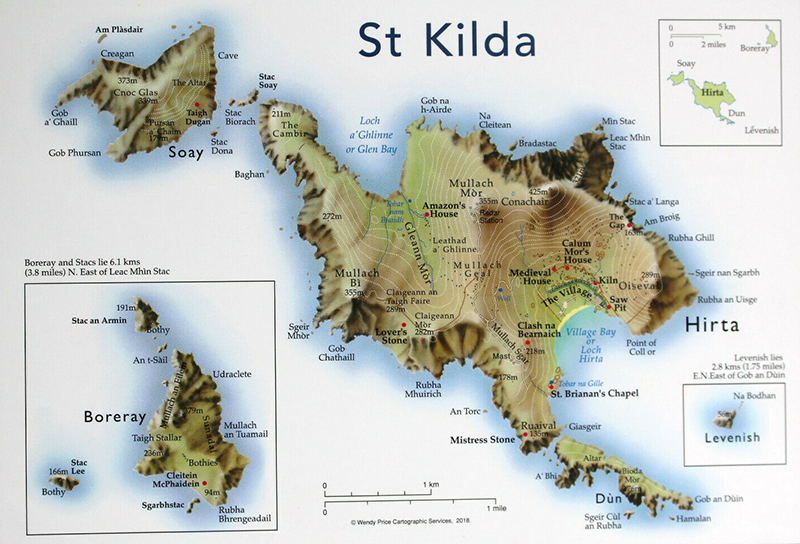

Contrary to what is generally believed St Kilda is not an island but an archipelago and its name does not derive from a saint’s name (nobody is really sure about its origin but there are several interesting hypotheses – some of them unveiling the colourful and expressive meaning of the ancient names: sunt kelda in Old Norse means “sweet wellwater”)

Soay shrouded in mist

“In the desert wastes of the North Atlantic a rock stack or a mountain-top breaks the surface. These specks of land represent the outermost regions of the British Isles and at times they are virtually inaccessible. Modern navigational aids locate them with ease but the weather can be so atrocious that landing is often impossible. Yet long ago prehistoric man arrived in his flimsy craft, settled and maintained some sort of intermittent communication with the main land.

The St Kilda archipelago is the largest island group in this section. It has a mystique all its own and I shall never forget our pleasure when Jandara first made landfall there.”

(The Scottish Islands – Hamish Haswell-Smith – Canongate 2004)

Mr Haswell-Smith’s book is a bestseller and has been re-edited a number of times. It is by far my favourite book about the Scottish islands. It is a big volume, full of very detailed maps and beautifully illustrated by the author. Nobody makes me dream about the Scottish islands as Mr Haswell-Smith does. His fascinating book is full of very interesting stories and anecdotes. That’s a traveller’s bible… and, by the way, very useful for the navigator.

“As a reference source Haswell-Smith’s book is invaluable…

a monumental labour of love that communicates the author’s own passion for island hopping

and combines it delightfully with his further talents as a painter and artist.”

(Daily Telegraph – from the backcover of The Scottish Islands)

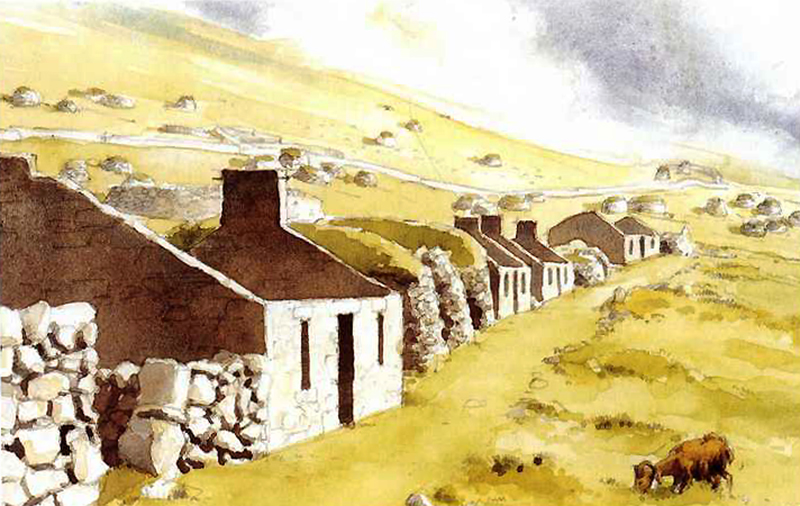

Hirta’s ‘High Street’ by Hamish Haswell-Smith The Scottish Islands

Mr Haswell-Smith is second to none to catch the atmosphere of a place! Is this a mouflon sheep I can see grazing on the field, in front of the ruined house?

Soay ram on Hirta

“Soay is the home of the species of horned sheep, Ovis aries, which were first brought to the British Isles about 5000BC. They are like mountain goats in appearance, wild, but unconcerned with man so long as man is unconcerned with them. Until the 1930s the sheep were entirely confined to Soay and were not to be found anywhere else.” (Hamish Haswell-Smith – The Scottish Islands)

“Through the camp [military camp] and among the village ruins wander primitive Soay sheep, untidily shedding their umber-coloured fleeces in the summer months. The population fluctuations of these evil-eyed, goat-like creatures are being studied with interest by scientists. The native St Kildans only kept domestic sheep on Hirta. They left the Soay sheep on their home territory of Soay.”

(Hamish Haswell-Smith – The Scottish Islands)

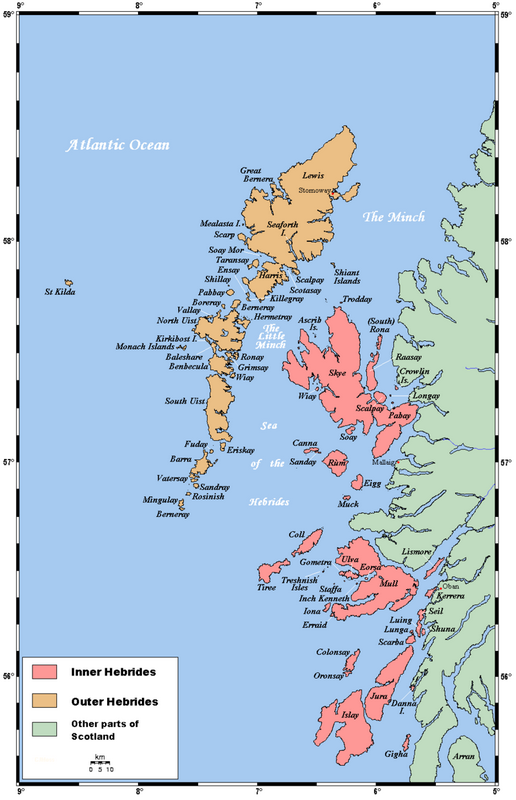

Hebrides in Scotland map

As we never went to St Kilda I’m making great use of maps and photos to try and get the best idea possible of these mythical and far away islands. The article on wikipedia is particularly well documented and I’ve added a number of books on my reading list too. It’s a pity I lack time to read all these books but a wonderful novel which I came across recently, quite by chance, made all the difference, as you will soon learn, reviving my dream to go to St Kilda and giving life to the austere geographical and historical facts I’ve learned here and there ;-).

St Kilda is part of the Scottish Outer Hebrides but when you look at the above map of the Inner and Outer Hebrides you immediately notice how isolated and small the archipelago appears, lost in the midst of the Atlantic Ocean. It is situated 64 kilometres (40 miles) west-northwest of North Uist and it is so small that our first impression on seeing it on the map is that there is only a single island there. In fact, as we shall see later, St Kilda is composed of four distinctive islands. Though it is situated 64 km from the nearest land, St Kilda can be visible, when the weather is fine, from as far away as the ridge line at the top of the Cuillin Mountains on the Isle of Skye, 129 km away. No chance for me, however, to contemplate the view from up there, so afraid I am of the heights !

St Kilda Village Bay Ian Mitchell Wikipedia

Just have a look at these pictures of St Kilda!

Can’t you feel the lure of the place with its solitary and wild beauty?

How strange these enigmatic stone buildings with their grass-covered roofs!

All these mysterious vestiges must bear witness to a very ancient history…

The Village Street of Hirta showing restoration work

A nostalgic atmosphere permeates the ruined houses of what has become a ghost village. Given the orientation of their façades one can easily imagine the people who lived there, peacefully sitting in front of their doors smoking a pipe, chatting, spinning or knitting… playful children and dogs… sheep grazing on the grassy slopes… and further on the cries of the many birds nesting in the cliffs…

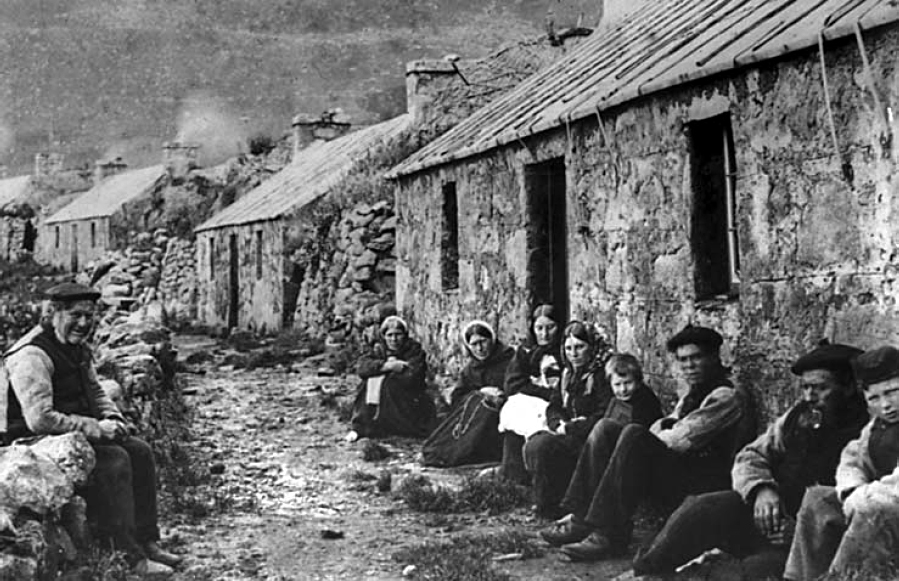

St. Kildans sitting on the village street, 1886. National Trust for Scotland

The history of St Kilda is unique and rather sad too, so far as the fate of its last inhabitants is concerned. People had lived there for at least two thousand years and were finally encouraged to leave the place, which they did on 29 August 1930, lured by the promises of a better life, weakened by the diseases of our modern world. Some of them did not survive long, most of them (if not all of them) suffered from homesickness…

“After two impossibly harsh winters, the 36 men and women still living on St Kilda were evacuated to Scotland. Many were provided with jobs working for the Forestry Commission – ironic, since they had never seen trees. They were desperately homesick, and most died before the outbreak of the Second World War, some of the common cold, which they had never before encountered. As they had prepared to depart from St Kilda, they had lit fires in their hearths, and left their bibles open at the Book of Exodus.”

(Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 73 © Maggie Fergusson 2022)

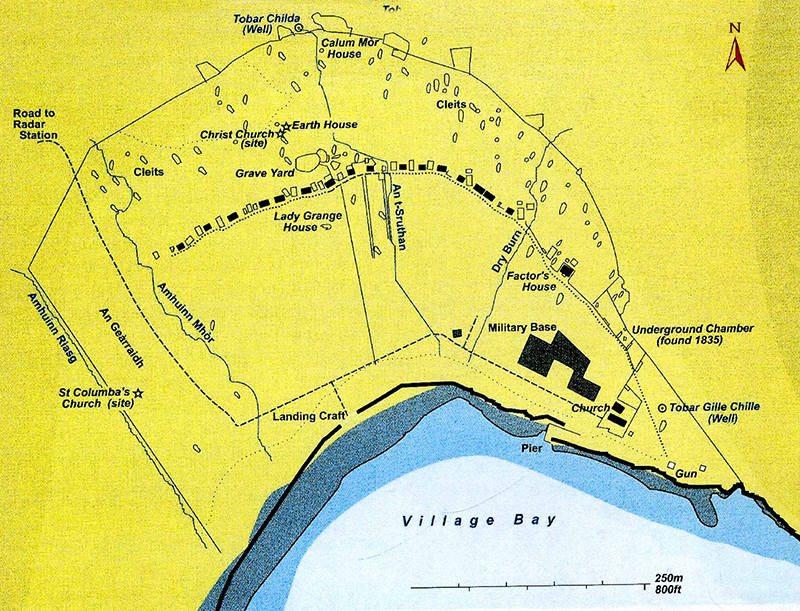

layout of the village of Hirta The Scottish Islands © Hamish Haswell-Smith 2022

“Village Bay in the south-east shelters the main settlement. Among the cottages and scattered up the mountain side are hundreds of small dry-stone structures with turf roofs called ‘cleits’ (Gaelic: a stone beehive bothy, water-tight but cross-ventilated). These were mainly used as larders for storing the sea-birds which were the St Kildans’ staple diet, but they were also used as general stores for fishing tackle, ropes, etc. The area is covered with dry-stone structures which are the product of centuries of effort.

In 1830 much of the original village was demolished and new black houses were built but most of the present cottages, which are gradually restored by the National Trust, were built in the 1860s to Victorian standards and using mortar joints.”

(Hamish Haswell-Smith – The Scottish Islands)

Portrait of Lady Grange St House

- Lady Grange House: The tumultuous life of this lady could fill pages and pages of a book. It’s worthy of an adventure novel. To cut a long story short let’s just say that, following family and political related disputes, Lady Grange was kidnapped and imprisoned in different places of Scotland before being deported first in The Monach Isles, 8 kilometres (5 mi) west of North Uist and then to St Kilda where she lived in deplorable conditions, conditions that a lady of her standing had probably never been used to. I’ve read in wikipedia that the “house” where Mrs Grange House lived was in fact a large cleit in the village meadows that is said to resemble “a giant Christmas pudding”. Boswell and Johnson discussed the subject in their 1773 tour of the Hebrides. Boswell wrote: “After dinner to-day, we talked of the extraordinary fact of Lady Grange’s being sent to St Kilda, and confined there for several years, without any means of relief. Dr Johnson said, if M’Leod would let it be known that he had such a place for naughty ladies, he might make it a very profitable island.” Lady Grange House died in Scotland in 1745. There is an interesting article in the Scotsman about this lady.

- Many ancient vestiges are scattered on the island: among them a souterrain dating from the period 400BC-500AD containing many artefacts (Hebridean Iron Age pottery, two Christian crosses engraved in stone, Viking brooches and a Viking sword)

Geographical notes

Map of St Kilda Scottish archipelago – Colin Baxter Photography

The archipelago of St Kilda is composed of four islands (Hirta, Dùn, Soay and Boreray) which are surrounded by a number of small stacks.

Boreray,_St_Kilda_viewed_from_the_north_-_geograph.org.uk_-_2598274

- The largest island of St Kilda is Hirta. Its sea cliffs are the highest in the United Kingdom, some being over 300 m (1000ft). Conachair is the highest peak (430 m – over 1400ft) but there are four other high peaks (Mullach Mòr 355m – Mullach Bì 355m…). It was the only island of the group to have been inhabited. There were 180 people in 1695, at the time of the visit of Martin Martin and only 36 in 1930 at the time of the evacuation. Zero people in 1931 and the houses had suddenly become silent… The smaller islands were used for grazing and seabird hunting.

- The island of Hirta is not a very large island measuring only 3.4 kilometres from east to west and 3.3 km from north to south but there is about 15 km of coastline.

- The only good landing place is in the shelter of Village Bay (Loch Hirta) on the southeast side of the island. Though the island slopes gently down to the sea at Glen Bay (at the western end of the north coast), landing is not easy there and quite perilous when the sea is rough.

- St Kilda is of volcanic origin. In The Islands of Scotland Hamish Haswell-Smith writes “When marine scientists conducted an underwater survey of the whole archipelago in 2000 they found that the separate islands were peaks of a single large mountain. About 18.000 years ago the sea level was approximately 120 metres lower than now and there is clear evidence of the ancient shoreline.” 120 metres lower than now : a sobering figure!

- Dùn is separated from Hirta by a shallow strait which is about 50 metres wide; more often than not the strait is impassable but sometimes it dries out. Perhaps with global warming it will run dry more often…

St Kilda Boreray with two great skuas on Conachair

Conachair, highest point of Hirta, St Kilda, with two great skuas. In the background are Stac an Armin, Stac Lee and Boreray

Historical notes

- The St Kilda islands were continuously populated from prehistoric times. Hirta seems to have been inhabited for about 3500 years. Hamish Haswell-Smith writes “In a study on behalf ot the National Trust for Scotland an ancient stone building was discovered near the top of a high cliff. The structure, possibly a place of worship or a tomb, is thought to date from the Bronze Age. Glen Bay is the site of a pre-viking settlement.”

- Hirta had been inhabited until 29 August 1930 when the 36 inhabitants were removed to the Scottish mainland.

- Evolution of the population:

- 1695: 180 (Martin Martin visited the island in 1697 and found the population “happier than the generality of mankind, as being the almost only people in the world who feel the swetness of true liberty”.)

- 1834: 93 (21 houses) Hamish Haswell-Smith writes : “As demand for the island’s ‘exports’ declined (fulmar oil for lamps, feathers, tweed), some of the men had to find work on the mainland. Thirty-six islanders emigrated to Australia in 1852 with State aid. Men were also lost at sea and in accidents on the cliffs, and there was severe infant mortality due to Tetanus infantus.”

- 1861: 78

- 1930 : 36

- 1931: 0

- 1961: 65 (military establishement)

- 1971: 65

- 1981: 46

- 1991: 0

- I’ve read in Wikipedia that after the Battle of Culloden in 1746, it was rumoured that Prince Charles Edward Stuart and some of his senior Jacobite aides had escaped to St Kilda. An expedition was launched, and in due course British soldiers were ferried ashore to Hirta. They found a deserted village, as the St Kildans, fearing pirates, had fled to caves to the west. When they were persuaded to come down, the soldiers discovered that the isolated natives knew nothing of the Prince and had never heard of King George II either…

- St Kilda was part of the Lordship of the Isles, then a property of the MacLeods of Dunvegan from 1498 until 1930 when the fifth Marquess of Bute donated it to the National Trust for Scotland. Hamish Haswell-Smith writes: “The islanders paid rent to the owners, the MacLeods of Harris and Dunvegan in Skye, who had been given the islands by a descendant of the Lord of the Isles. The rent was paid in the form of produce such as tweed, wool, feathers or oil from the sea-birds and once a year a steward called from Harris to collect the goods. At that time visitors reported a surprising level of general prosperity among the islanders although they held everything in common ownership and had no personal property. They also had no leadership structure. A ‘Parliament’ would meet each day to decide what work had to be done. This was by general agreement, but there were occasions when it could take all day to reach a decision!”

- A history of Village Bay on Hirta states that some improvements in housing were made in the 1830s by the “landlord and the Rev. Neil MacKenzie“. The report adds that “the old village further up the hill was replaced by a crescent of blackhouses … Those were damaged by a hurricane, and in 1861, 16 new dwellings replaced the blackhouses which were relegated to byres”.

- The beginning of the end: it began in 1834 with the first tourist ship to call at the island, The Glenalbyn. Hamish Haswell-Smith writes: “it marked the start of the loss of the islanders’ independence and the end of St Kilda. They were almost completely naive and were cheated out of many of their essential possessions by the tourists. They came to rely on modern communications and a post-office was opened on the island in 1899 but this was really to satisfy tourists”. (HHS)

- “The other vital contribution to the eventual collapse of society on the island was the hell-fire and damnation of crusading Christian ministers. By far the most notorious was the Rev John Mackay who was resident from 1868 to 1889. By the end of his evil ministry the islanders had been browbeaten into so much church attendance every day of the week that there was insuficient time for growing and gathering food.” (HHS)

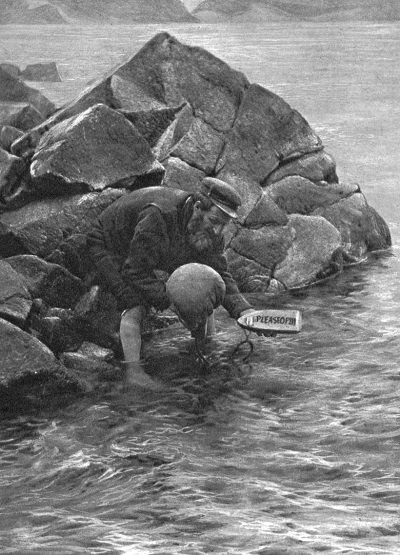

Launching the St Kilda mailboat

“Une bouteille à la mer !”

“If they felt the need to send letters to the mainland, the St Kildans would stuff them into ‘mailboats’ – hollowed-out lumps of wood inscribed PLEASE OPEN – and launched them into the sea like messages in bottles. If they required more urgent attention, they lit bonfires, hoping to catch the attention of crofters 45 miles east on North Uist.”

(Extract from Slightly Foxed Issue 73 © Maggie Fergusson 2022)

- Apart from imported diseases the islanders were healthy except for ‘eight-day sickness’ which was ‘God’s will’ and killed 80% of the babies born. In the 1890s it was discovered that the source of the disease was tetanus, probably contracted from the fulmar oil which was traditionally used to anoint the umbilicus. The new minister, unlike his predecessor, took lessons in midwifery in Glasgow in order to persuade the islanders that God disapproved of this tradition.” (HHS)

- 1912: a wireless transmitter was installed by the Government which led, during WWI, to the shelling of the island by a German submarine (material damage but no casualties). A gun was then installed to defend Village Bay but it has never been fired.

-

Gun_Dùn_St_Kilda

- “After WWI conditions continued to deteriorate. Many of the active young men emigrated leaving the aged and the very young. Eventually matters became so desperate that the thirty-six remaining St Kildans were more-or-less compelled to agree to evacuation. They were persuaded to do so by Nurse Williamina Barclay who, in 1927, had been sent to assist them.”(HHS)

- WWII: The islands saw no military activity during the Second World War, remaining uninhabited, but three aircraft crash sites remain from that period. A Beaufighter LX798 based at Port Ellen on Islay crashed into Conachair within 100 metres (328 ft) of the summit on the night of 3–4 June 1943. A year later, just before midnight on 7 June 1944, the day after D-Day, a Sunderland flying boat ML858 was wrecked at the head of Gleann Mòr. A small plaque in the church is dedicated to those who died in this accident. A Wellington bomber crashed on the south coast of Soay in 1942 or 1943.

The tracking tower on Mullach Sgar

- In 1955 the British government decided to incorporate St Kilda into a missile tracking range based in Benbecula, where test firings and flights are carried out. Thus in 1957 St Kilda became permanently inhabited once again. A variety of military buildings and masts have since been erected, including a canteen (which is not open to the public), the Puff Inn. The Ministry of Defence leases St Kilda from the National Trust for Scotland for a nominal fee.

- Hirta is still occupied year-round by a small number of civilians employed by defence contractor QinetiQ working in the military base (Deep Sea Range) on a monthly rotation. In 2009 the MoD announced that it was considering closing down its missile testing ranges in the Western Isles, potentially leaving the Hirta base unmanned. In 2015 the base had to be temporarily evacuated due to adverse weather conditions. In summer 2018, the MOD facilities were being restored as part of building a new base; one report stated that the project included “replacing aged generators and accommodation blocks”.

- With no permanent population, the island population can vary between 20 and 70, most living here temporarily. These inhabitants include: MoD employees, National Trust for Scotland employees, and several scientists working on a Soay sheep research project

How I discovered a great novel about St Kilda

I love history but I’ve always liked to learn it through historical novels – maybe you remember I’m a fan of Sir Walter Scott to whom I made a promise 😉

Recently I fell upon such a novel about St Kilda 😉

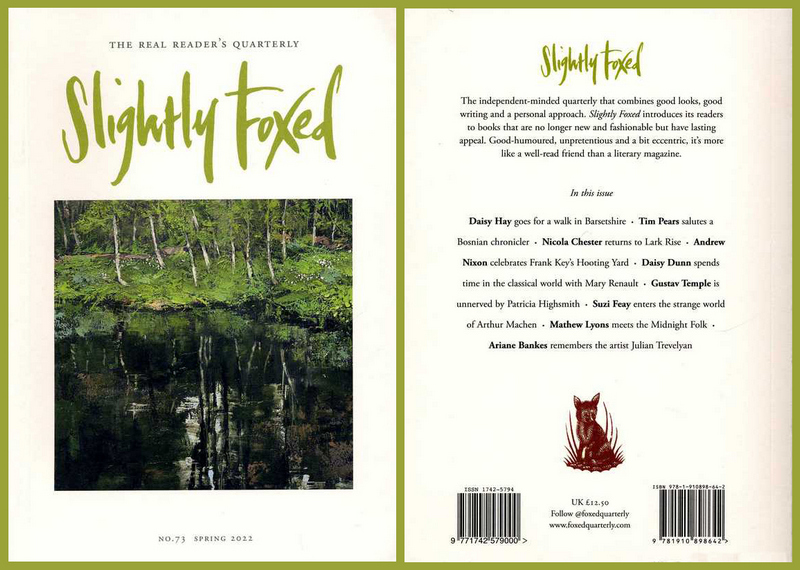

Slightly Foxed 73 fond vert clair r1

Some time ago, I received the spring issue of Slightly Foxed, one of my favourite English literary magazines. Slightly Foxed publishing house was created in 2004 by Gail Pirkis and Hazel Wood, both of them passionate about their work, as it is clearly expressed in their page of introduction of the magazine:

Welcome to the first issue of Slightly Foxed, the magazine for adventurous readers – people who want to explore beyond the familiar territory of the national review pages and magazines, and who are interested in books that last rather than those that are simply fashionable. We plan to bring you, each quarter, a selection of books that have passed the test of time, that have excited, fascinated or influenced our contributors, and to which they return for pleasure, comfort or escape; the kind of books that sell steadily and quietly to those who know about them, but are no longer to be found on the review pages or sometimes even on the bookshop shelves. (…)

Being a quarterly of individual enthusiasms rather than conventional reviews, Slightly Foxed is by nature serendipitous, and we have decided to reflect this in the way it is laid out – not by categories, but more as a kind of mystery tour during which you may chance upon something that catches your interest – possibly the kind of book you might not have previously considered reading. (…)

(Gail Pirkis & Hazel Wood – Slightly Foxed 1 – Spring 2004)

“you may chance upon something that catches your interest”… that’s exactly what happened to me on opening Slightly Foxed number 73 published in Spring 2022… first on discovering a familiar author and second on discovering the subject of her review 😉

The author was Maggie Fergusson, a journalist and author who is well-known for her very good biography of George Mackay Brown. Maggie Fergusson did know GMB personally and she even became a friend of him. Two shelves of my library are devoted to GMB and I put Maggie’s biography next to his books.

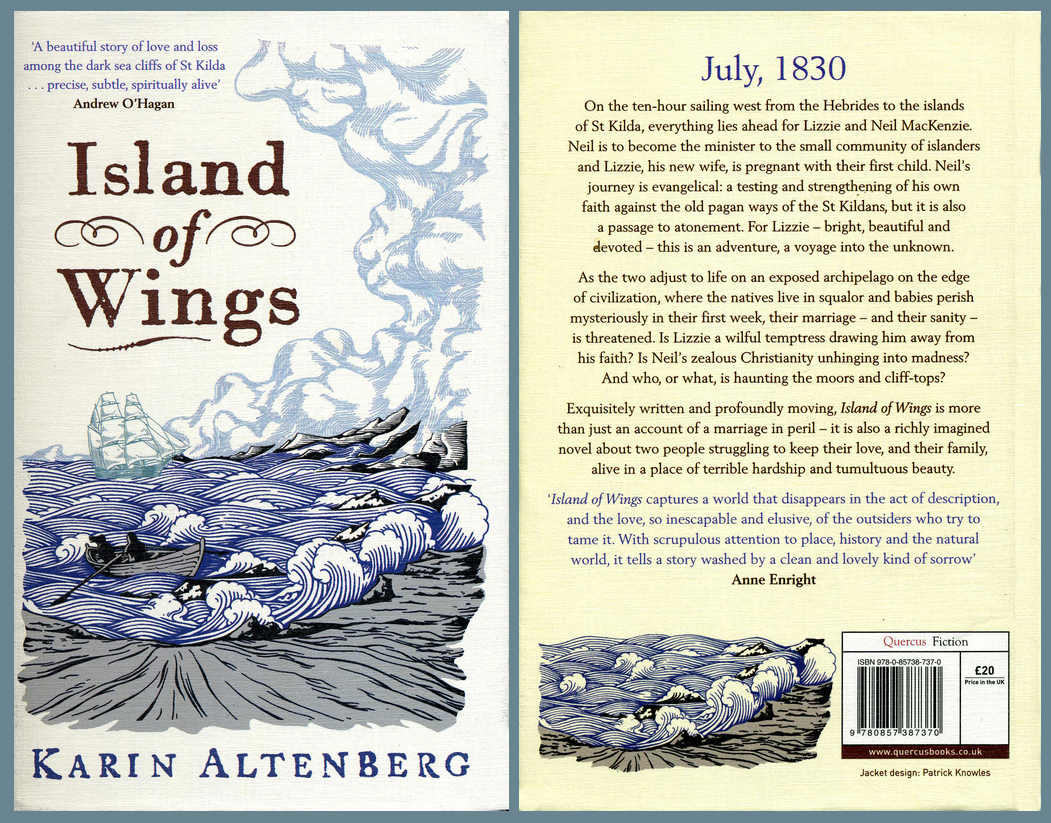

Maggie Fergusson’s article about St Kilda is entitled “Fulmar, Gannet and Puffin”. She has always dreamed to go to St Kilda and she describes how she was surprised on discovering that a fan of St Kilda was living not far from her house in London. Karin Altenberg, her neighbour, is an archaeologist by profession and not only did she go to St Kilda but decided to write a novel which would take place there. Maggie introduces Karin Altenberg’s book which is entitled Island of Wings.

In shelves to the left and right of the fireplace in our dining-room, my husband keeps an extensive collection of books about Scotland. Half a shelf is given over to volumes on St Kilda. If ever I feel the need to escape from Hammersmith to a landscape of vast skies, mountainous waves, sea-spray blowing like white mares’ tails across the rocks, this is where I turn: to the extraordinary archipelago, 110 miles west of the Scottish mainland, whose black cliffs and dizzying stacks, the highest in Britain, unfold in a drumroll of Gaelic names – Mullach Mor, Mullach Bi, Conachair.

St Kilda is top of the list of places I hope to visit before I die. So imagine my amazement when I discovered that two roads away from us in London lives a woman who has not only been there, but has also written a novel based on Hirta, the main island. An archaeologist by training, Karin Altenberg was fed up with her job when she decided to journey to St Kilda, to blow away the cobwebs and think clearly about her future. She was to have travelled to the islands with a lobster fisherman but – as often happens – the Atlantic surges were too perilous. She caught a lift instead on a yacht. After eight hours’ sailing, the cliffs of St Kilda loomed up ahead – ‘like Mordor’, says Karin’s partner, the poet Robin Robertson. The clouds lifted and the sun came out. The combination of light and mist was, Karin says, ‘otherworldly’. No visitor is allowed to stay on St Kilda, so in the few hours she had there she rushed about taking in everything she could – the ‘clachan’, a huddle of oval dwellings, a bit like puffin burrows, in which the St Kildans lived until the mid-nineteenth century; the stone houses of the ‘new’ village; the plain, austere church built to plans drawn up by the great lighthouse builder Robert Stevenson (grandfather of Robert Louis). As she re-boarded the yacht to sail back to Scotland, an idea began to form in her mind. She would capture St Kilda not by employing her training as an archaeologist and historian, but through fiction. Island of Wings, published in 2011, centres on a real Church of Scotland minister, Neil MacKenzie, who arrived on St Kilda in 1829 with his wife, Lizzie. (…)

Portrait of Karin Altenberg featuring on the back cover of Island of Wings © Paula Tranströmer

Karin Altenberg was born in Sweden and moved to Britain to study. Novelist and occasional translator she lives between Sweden and Britain and within two languages.

In her first novel, Island of Wings (Quercus, 2011), a missionary and his young wife struggle for love and existence on the remote island of St Kilda in the early nineteenth century. The book was nominated for the Orange prize, the Saltire First Book and the Scottish Book of the Year.

Karin Altenberg has a PhD in archaeology from the University of Reading and her background as a landscape archaeologist has influenced her writing, with landscape always playing a central part in her novels about people on the edges of the world.

She has received fellowships to writers’ residencies in Italy, reviews regularly for the Wall Street Journal and also writes for the Guardian, the Irish Times and Slightly Foxed.

Maggie’s article immediately made me want to read Karen Altenberg’s novel. So far, I’ve read just over half of Island of Wings and I can’t say much more about the novel except that I have been captivated since the first page of the book. Karen is really a born story-teller and knows her subject perfectly. She must have observed everything with the eye of an archaeologist for though she didn’t spend more than one day on St Kilda she has got a deep sense of the place. The characters have been created from people who actually existed (Neil Mackenzie the minister and his wife Lizzie to mention only the main characters). These characters are very lively and endearing (Bettie, Anna, the native people, the ornithologist and his brother…). We are drawn to feel empathy with the women, especially Lizzie who not only has to adapt to a harsh life but must also face terrible hardships (the loss of her newborn babies, relationship problems with her husband). Karen very well manages to bring the past to life while also making us feel the omnipresence of the invisible. The atmosphere is sometimes heavy and disquieting. We learn much about the local customs, the myths and legends while asking ourselves questions about the influence of religion, of civilization and progress. And last but not least, Karen is writing so beautifully. Who could guess her mother tongue is not English?

A book to read and re-read, preferably with a map of St Kilda at hand ;-).

Below are a few extracts of Island of Wings :

The_slopes_of_Ruabhal_and_Mullach_Sgar_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1470520

The southern tip of the main island of St Kilda, with Village Bay and Conachair, the highest point, beyond.

Arrival of Reverend MacKenzie and his wife on Hirta :

“Lizzie drew closer to her husband. She was speechless and did not know what to make of this island, which was so unlike any other place she had ever seen or even imagined. How could anynone live in a world as strange as this? (…)

They drew up towards the wind and turned into a wide bay where the treacherous black rocks gave way to a shore fringed by a narrow shingle beach, sloping gently up towards a hamlet surrounded by green pastures. Behind the hamlet the ground rose gradually at first and then steeply to the slopes of Ruiaval, as the Captain called it, to the south and the rugged face of Conachair to the north. The many colours of warm earth, fresh sorrel and young heather were at once pleasing to the sailors’ eyes, which had grown accustomed to a dreary palette of black, white and grey. In the lee of the wind the evening seemed suddenly warm and agreeable. They were beginning to hear new, more vibrant noises carried from the shore – dogs were barking through the cacophony of birds, and Lizzie thought she could hear the mountain voices of excited children.

As they looked closer the Mackenzies could see little stone structures spotted across the hillside above the village. They seemed almost organic, as if they were growing out of the rough ground like boils. These were cleints – Mr Bethune explained – where the natives would dry their turf and store their food and feathers. The absence of trees was striking. Lizzie had never seen such a barren place.

On the right side of the bay the sea cliffs, covered in short grass and crawling lichen and littered with more of the strange stone structures, rose steeply towards the high mountain, partly hidden by a great cloud of wooly mist. Small sheep with coats of a blackish brown were clinging to the sheer cliffs, their hooves aptly finding footholds in the most impossible places. Some of them looked up as the cutter drew nearer, chewing in stupid curiosity.

MacKenzie suddenly gasped as he laid eyes on his church and manse at the foot of the hill to the right. The white-washed buildings shone brightly against all the brownish green and he was surprised that it had taken him so long to spot his new home.”

I intend to read more books about St Kilda. I’ve already downloaded on my kindle Tom Steel’s book The Life & Death of St Kilda and Charles Maclean’s Island on the Edge of the World. I must have Martin Martin’s Description of The Western Islands of Scotland which contains “A Voyage to St Kilda” but this book must still be in the boxes, waiting to find a place on my bookshelves (as many other ones)…

Hamish Haswell-Smith’s The Scottish Islands and Karin Altenberg’s Island of Wings are open on my desk. Below are a list of more books to read but of course my list is not exhaustive and it is evolutive…

A short bibliography

- The Scottish Islands, Hamish Haswell-Smith – Canongate Edinburgh 2004.

- Island of Wings Karin Altenberg – Quercus 2011

- The Life & Death of St Kilda by Tom Steele

- Island on the Edge of the World: the Story of St. Kilda by Charles Maclean – Canongate Édimbourg, 1972. Réimpression de 2006

- Description of The Western Islands of Scotland by Martin Martin –”A Voyage to St Kilda”.

- St Kilda and the Wider World: Tales of an Iconic Island by Andrew Fleming – Windgather Press, 2005,

- St Kilda by David Quine – Colin Baxter Island Guides, 2000,

I dedicate this post to the memory of Hamish Haswell-Smith who died on 27 August 2019. I’ve just learned this news and it makes me sad, though I’m sure he lived up to his dreams while sharing them with many.

I hope this page will make you want to know more about St Kilda and, why not, go and discover these remote islands, a paradise for ornithologists, geologists, archaeologists, historians, writers, photographers and artists, or mere travellers (as we are) irresistibly attracted by the wild and solitary beauty of Scotland and more especially Scottish islands…

Bonne lecture !

Á bientôt. Mairiuna.

Leave a Reply