Bonjour Janice, Marie-Agnès et Jean-Claude – Hello again from Scotland! 🙂

Marie-Agnès and Jean-Claude, do you still have a subscription to The Scots Magazine, the famous journal first published in 1739?

We don’t have one ourselves, but were interested to find that the October 2011 issue contained a number of features on music in Scotland. Amongst them was a piece entitled Celtic Connections – Scotland’s links with the Classical World, tracing in just a few hundred words Scotland’s many associations with music of the classical period – by Garry Fraser, I think, for the author’s name was not given!

Garry begins with Felix Mendelssohn (1809-47) whose visit to Scotland in 1829 inspired his Hebrides Overture as well as his Scottish Symphony; the other great composer to travel around Scotland was, of course, Frederic Chopin (1810-49) about whom you recently wrote on Scotiana, Marie-Agnès! (The Scottish Autumn of Frederic Chopin.) Franz Liszt (1811-86) also came briefly to Scotland to play in the 1840’s, in the course of the long recital tours he undertook.

And many composers who’d never visited were nevertheless inspired by Scotland and its culture. Garry mentions Max Bruch’s Scottish Fantasy and Malcolm Arnold’s Four Scottish Dances; songs of Robert Burns were given settings most famously by Beethoven, Haydn and Mendelssohn, but also by Schumann, Shostakovich and Benjamin Britten! Berlioz, perhaps best known in Scotland for his stirring arrangement of La Marseillaise, admired the writing of Sir Walter Scott, which inspired his Waverley Overture of 1827.

'Two Strings to her Bow' is by the artist John Pettie, RA. The girl is his daughter, Alison; the young man on her right - with dark hair and stick - is Hamish MacCunn. He and Miss Pettie had met at Corrie, on the island of Arran, where the artist loved to paint. The young people were married in London in 1888.

Hamish MacCunn (1868-1916) is the best-remembered today of the Scottish-born composers of the classical period; his atmospheric and evocative overture Land of the Mountain and the Flood (1887) – written when MacCunn was just 19 – has remained immensely popular. Marie-Agnès, Janice, Jean-Claude, I’m sure you’ll recognise this title as a line from the prolific Sir Walter Scott! 🙂

Writing of Land of the Mountain and the Flood – and the two subsequent overtures – A M Henderson says in his charming little book Musical Memories (Grant, 1938): “These works alone would have established MacCunn’s claim to a place in the history of Scottish music, and in the affection of Scottish people for all time. They are not only full of originality and splendidly orchestrated, they are all unmistakably Scottish. They breathe the air of mountain and moorland, and from first note to last, Scotland is their theme.

A few years after the appearance of A M Henderson’s book, doubt emerged as to the true identity of the girl in Pettie’s painting. Stuart Scott published last year at MusicWeb International an excellent short biography of Hamish MacCunn, in which she is named as Miss Margaret Thallon (governess to both the MacCunn and the Pettie families) and the second young man as Mr Alec Watt. “

Of MacCunn himself, who died at just 48, Henderson writes: “He leaves behind him the memory of a charming and unselfish personality .. .. in the music of MacCunn are the lasting qualities of beauty and sincerity. Is it not fitting that, in his native land at least, we should try to keep his memory green?”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vA2HldDSmD4

Garry Fraser ends his review with three lesser-known Scottish classical composers – Sir Alexander Mackenzie (1847-1935) author of the suite Pibroch for Violin and Orchestra; Sir William Wallace (1860-1940) who composed a symphonic poem inspired by his namesake, the heroic Scottish patriot; and Frederic Lamond (1868-1948) who composed – amongst other works – a concert overture From the Scottish Highlands, inspired by Quentin Durward, one of Louis XI’s Scottish bodyguard. (We’re back to Scott, again!)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R9OPelGM9GI

But composing was the least of what Frederic Lamond did, for he was by far the most accomplished pianist that Scotland has ever produced, and in his day was held to be the greatest interpreter of Beethoven’s keyboard works. I first began to be interested in Lamond – scarcely knowing his name – on hearing of a tribute that was paid to him by the curators of the Beethovenhaus, Bonn. When, early in 1948, news reached them of the death of the great Scottish pianist, Lamond’s portrait was placed there in a rare act of homage.

Let’s begin by looking at the notice of Dr Lamond’s passing in The Glasgow Herald of February 23, 1948:

“DEATH OF CELEBRATED GLASGOW PIANIST

Lamond’s Memorable War-Time Recitals

Dr Frederic Lamond, the famous Glasgow pianist, who early in his career played mostly on the Continent, died in a Stirling nursing home on Saturday at the age of 80. The recitals he gave in the Athenaeum Theatre, Glasgow, during the Second World War were memorable .. .. In 1941, he was twice injured in street accidents (‘blackout’ conditions greatly increased the danger) .. ..

Frederic Lamond enjoyed a career of sustained success. He was a pianist first of all. But he had studied the violin in his youth, and when he first went to the Continent took also composition at the Raff Conservatoire ( Frankfurt am Main). As composer he wrote in the style of the 19th century, and mainly during the first years of his professional career .. ..

Lamond’s début in Glasgow (1886, at the age of 18) was followed by a series of recitals in London. It was a great tribute to the young Lamond that Franz Liszt attended one of these during his last visit to this country, and only a few months before he died at Bayreuth .. ..

In the 1880’s, Germany was the centre of gravity in musical matters, and Lamond had already found in the Continental atmosphere the best air for breathing. He lived in Berlin, and in 1917 was appointed professor of piano at The Hague Conservatoire .. ..Lamond’s elder brother David was an esteemed musician in Glasgow. David remained at home, teaching, sharing in the musical activities of the city, and following with keen satisfaction the brilliant career of Frederic. He had been Frederic’s first teacher, and had the early reward of seeing the boy appointed at the age of 12 to the post of organist at Laurieston Parish Church .. ..

Lamond was most to be enjoyed at recitals, and during an evening’s playing seldom failed to do some magical things. These inspired and inspiring moments were mainly called forth in Beethoven and Brahms .. ..

Lamond has been charged with confining his choice of Beethoven works within a narrow limit of first favourites. But he had himself explained in a private talk that the programme promoters were to blame; they would not allow that the public wished to hear from him anything but the ‘Appassionata’ or the ‘Emperor’. The public were the losers, and it is not clear that the concert promoters gained .. ..

In 1937 the University of Glasgow conferred on Lamond the degree of LL.D. When proposing the health of the Chancellor at the luncheon, Dr Lamond said that he had received his first musical impressions in Glasgow during the season 1877-78, when von Bülow conducted under the auspices of the Glasgow Choral Union. He was only a boy of nine at the time, and it was his privilege later to become the disciple of that extraordinary man. Bülow’s widow had given him a beautiful baton which the committee of the Choral Union had presented to her husband on his departure from Glasgow. Lamond took the opportunity of now offering the baton to Glasgow University as a slight mark of his profound appreciation of the honour conferred on him .. ..

There was great satisfaction in Glasgow when Lamond, shortly before the Second World War, returned to settle in his native city .. .. His association as teacher with the work of the Royal Scottish Academy of Music (to become the RSAMD; now The Royal Conservatoire of Scotland) brought in the students to swell the ranks of his admirers. For the wider public of Glasgow, the series of recitals he gave in the Athenaeum Theatre were features of the war years. It was felt by many in the audience that in these recitals Lamond showed his musicianship as never before.

Dr Lamond is survived by his wife, formerly Irene Triesch, a celebrated actress in Vienna, and a daughter.”

Dr Ernest Bullock, Principal of the Royal Scottish Academy of Music, added a few words:

“The death of Dr Frederic Lamond is a great loss to music. He was a pianist of international fame, unequalled as an interpreter of Beethoven’s pianoforte works, and a musician of the highest integrity. He was also a man who possessed not only a touch of genius in his art, but kindliness, sympathy and human understanding with all young musicians of ability, irrespective of whether they were his pupils or not.

Many happy memories of him will long remain with us at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music.”

Next day (24 February, 1948) this paragraph appeared in the Stirling Observer newspaper:

“The greatest pianist that Scotland ever produced, and a supreme interpreter of the music of Beethoven, Dr Frederic Lamond, died in a Stirling nursing home on Saturday morning, where he had been a patient for the past fortnight. A gramophone and his own records of Beethoven were at his bedside, for it was the wish of the great pianist that he should pass away to the exquisite music of his beloved composer. With his leonine head and massive brow, Lamond bore a strong resemblance to Beethoven. Aged eighty and a native of Glasgow, he was the last surviving pupil of Liszt. For more than fifty years he was recognised as one of the most brilliant exponents of pianoforte, and was acclaimed in every capital of Europe and America.”

Generous tributes to a great musician and artist. I’m fortunate to have a copy of The Memoirs of Frederic Lamond (Published by William MacLellan, Glasgow, 1949) now a very rare book. (Mr MacLellan’s wife, Agnes Walker, was herself a noted concert pianist.) In his Foreword, the eminent critic Ernest Newman writes:

“The reader must not expect to find in the following pages anything resembling the usual autobiography .. .. The book is a record of the heroic struggle of one whose career as a musician was begun and continued under every imaginable disadvantage and discouragement – his own early poverty and that of almost everyone to whom he might turn with any hopefulness for help; his lack of influential social connections; the handicap of having to make his first way in a foreign country; and then, in the maturity of his powers, the relative lack of appreciation he received in his own land .. ..

” Throughout his life the supreme god of Lamond’s worship was Beethoven, whom he studied and reflected upon from his first days to his last: even as a boy his instinct set him at grips with the problems, both technical and imaginative, of the great Hammerklavier sonata, a work of which most public performers at that time fought shy.

In the course of time he came almost, as a pianist, to create a Beethoven of his own, a Beethoven too dynamic for many of his British listeners, who were at the same time startled by the power that Lamond infused into the more tremendous moments of the music and insensitive to the fineness of his tone-spinning in its gentler moods.

All in all, he was not appreciated here as he was on the Continent; his way of thinking in music was always big and fundamental, qualities which for a long time made less impression on simple-minded British concert-goers than virtuosity for virtuosity’s sake did and still mostly does.

If occasionally, in his ardour for what was most titanic in Beethoven, he demanded more of the piano than the instrument was willing to give him – well, Beethoven himself, both as composer and as player, was often up against the same difficulty, and I think he would have been on Lamond’s side. For the rest, let the reader who wants to realise the fundamental integrity and virility of Lamond’s nature, and his undiscourageable steadfastness in the pursuit of his ideal, turn to the pages that follow .. .. “

In her Introduction, Irene Triesch Lamond (1877-1964) widow of the great pianist, writes:

“Frederic Lamond intended to write his memoirs .. .. At 78, when his physical illness became too apparent, he was forced to give up his concert career.

He began to collect his memoirs and to write them down – but, alas, the spirit was tired and the pen fell from his weak hand. So nothing but a fragment remained, which I want to convey to the musical world with a few words concerning his personality .. ..“The sympathies he acquired throughout his long life in foreign countries never deterred him from preserving true attachment for his own country. However, the moral and intellectual foundations of Europe at its best became the corner-stones of his innermost personality .. ..

Music widened and deepened the universalism of his spirit – what more could he contribute to the honour of the country of his birth?”

And in her Postscript she adds:

Frédéric Lamond His Wife & Daughter -The Memoirs of Frederic, Lamond William MacLellan, Glasgow,1949

“I lived in Frederic’s world for 46 years – a blessing for which I thank heaven. I remember our unison in music. As the companion of such a man, who was an artist to the very depths of his soul, I learned to honour Beethoven’s magnificent music .. ..

“How it touched me and how overwhelmed I was! How rapturously everything sang and sounded when he played to me!

Beethoven! Everything that had ever been called longing, grief or rapture – in unspeakable spirituality! Beethoven! Expresses all happiness which ever trembled in human heart, all greatness, to think of which we feel completely overwhelmed!

” ‘Continuing to learn’ was Frederic Lamond’s principle. With what patience did he work at the handicraft of his art! Work began for him in the morning, and at night work still lived in the quivering of his hands when he slept. ‘If I work continuously, my conscience is clear’ .. ..

“Frederic had a great interest in the theatre, particularly in the drama. I was engaged at the ‘Deutsches Theater’ in Berlin .. .. Frederic gave up his home of many years in Frankfurt to follow me to Berlin. We married (1904).

Ours was a rich but strenuous life and we were often separated for long periods. Year in, year out: concerts, tours into foreign countries .. .. but when free we cherished all the more the rare hours of relaxation in our beautiful home.

“Frederic’s very large and high music room contained a rare library with books in all living languages. Then there were the manifold scores of all the great composers of the past and of our own day. Beethoven’s marble bust stood on a high, ebony column; then came Liszt’s bust and two Bechstein grands, and some lovely pictures. Whenever I entered the music room I felt as in a temple.”

Frederic would often help his wife to rehearse her rôles:

“Those were happy, unforgettable times, when he played his programme ‘as a rehearsal’, and when I played my rôles before him and listened to his words of wisdom.

A few days before his death, he said to me: ‘Do you remember, Irene, the happy times, when we studied together?’ Yes, we were happy, my Fred! .. .. Oh! Where is the human being who does not know the longing for lost happiness?

“When death was approaching – he was not afraid of it – in his great suffering he showed strength and brave resignation .. ..”

Frederic Lamond was born in the poor east-end of Glasgow on January 28, 1868; his family roots were in the Bridgeton and Cambuslang areas – a ‘musical’ family, one might say. Young Frederick took to the keyboard like a duckling taking to water. Marie-Agnès, Janice, Jean-Claude, I expect you have an expression just like that in French!

Isn’t it time I shared with you a little of Lamond’s own writing?

“It was David who taught me the rudiments of music. (Lamond’s brother, 19 years his senior, to whose memory the book is dedicated.) In 1878, I, a boy of 10, was appointed organist at Newhall Parish Church (Glasgow) my father officiating as choirmaster. I had to study four organ voluntaries for each Sunday .. .. As my legs were not long enough to reach the pedals, a substantial piece had to be sawn off the organ seat, otherwise my duties cost me little trouble .. .. “

So the appointment as organist to which The Glasgow Herald’s writer refers, was in fact young Lamond’s second such appointment!

“It was my fate to become known in Glasgow musical circles as a prodigy, a kind of wonder child. A committee was formed, consisting of one lady and three gentlemen, which was to provide financial support for the continuance of my education in London .. .. but it suddenly became deaf, and that was the end of my London training. To finish my musical studies in Germany became my ambition .. .. In September 1882, my brother David, the two younger sisters, Elizabeth and Isabella, and myself, set out for Frankfurt .. .. “

Lamond had not yet attained his 15th birthday.

Wikipedia suggests that by the turn of the 20th century – when Lamond was in his early 30’s – he had perhaps reached the height of his powers. These were still the early days of records. Lamond made what is thought to be the first complete recording of Beethoven’s Emperor concerto (No 5 in E Flat Major, Opus 73) for HMV, ‘His Master’s Voice’ in 1922 – by the old ‘acoustic’ process, Eugène Goossens conducting. (The complete work called for five double-sided 12-inch discs. Electrical recording, using sophisticated microphones, came along in 1925, although many music-lovers still used hand-wound acoustic gramophones at home.)

Chers Amis, I have several times confessed to you my interest in the old shellac records! Consulting the 1935 Catalogue of HMV Records, I found that Lamond’s Emperor recording had been deleted in favour of newer, electrical recordings of this work by the Austrian-born Artur Schnabel (1882-1951) and the German Wilhelm Backhaus (1884-1969). Dear friends, perhaps we ought to stand quietly for a moment now, for we are in distinguished company! Both of these younger men were Celebrity Artists of ‘His Master’s Voice’, their discs issued with distinctive scarlet labels. Their growing reputations threatened that of Lamond; but by the mid-1920’s the Scots-born pianist was over 55 years of age, and for 30 years had reigned supreme.

“Schnabel’s records of the Beethoven concertos Nos. 1, 3, 4 and 5 will stand for all time as the ideal performances. When the Beethoven Sonata Society was formed in 1932 by HMV, the complete recording of the 32 piano sonatas was entrusted to Schnabel.”

So declared the editor of HMV’s catalogue. And Backhaus?

“Wilhelm Backhaus was born in Leipzig in 1884, and at the age of 10 entered the Conservatoire there .. .. his first recitals in 1900 created a profound impression, and in 1905 (aged just 21!) he was appointed principal Professor of Piano at the Royal College of Music, Manchester. His interpretations are notable for their delightful ease of execution and profound musical insight .. ..”

The Lamonds spent the years of the First World War outside Germany. In the 1930’s they became increasingly alarmed by the policies of the Third Reich, for Irene Triesch had Jewish blood in her veins; as the threat of war again approached, they abandoned their beautiful home in Berlin and fled to Scotland. Frederic Lamond had retained his British nationality, as well as his fondness for the land of his birth.

“There is something about the country a man is born in, that catches him and draws him back .. .. “ How true are these words of the great tenor John, Count McCormack (1884-1945) one of my most-admired musical personalities! McCormack, sadly, was not a Scotsman, although his mother (Miss Hannah Watson) was from Galashiels in the borders. Born at Athlone, Ireland, John McCormack retired to Dublin after a glittering international career, dying at a pretty spot on the coast called Booterstown when he was just 61. Enrolled in the Legion d’Honneur – in 1924, I think – he was fêted around the world; there’s no more romantic story in all music.

(See I Hear You Calling Me by Lily McCormack, John’s widow; Bruce, NY, 1949; W H Allen, London, 1950. This charming little book is not at all expensive; Lily wrote it – most beautifully – while staying with family friends in New York. There’s warmth and affection on every page.)

Now, who are our two Opera Stars? (Yes, I know that McCormack was the youngest principal tenor at Covent Garden in 1907, but he much preferred the concert platform!)

I may be mistaken in this, but I’m sure we’ve mentioned them both in our regular emails; now, who could they be? Both were born in Scotland, and both died here; one at the age of 93, the other in her 93rd year! And both were relatively unknown in their native land, despite – or perhaps because of – long international careers. I’m thinking, of course, of Joseph Hislop (1884-1977) of Edinburgh and Mary Garden (1874-1967) from Aberdeen.

Ladies first! Leaving Scotland at the age of nine, Mary Garden spent her formative years in the USA – and in time was to become an American citizen. Her début at the Opéra-Comique, Paris, in 1900 caused a sensation. Who was this pretty young woman of 26, who not only sang beautifully, but was a consummate actress with a compelling stage presence? She took the title rôle in Charpentier’s Louise, André Messager conducting. Messager and Miss Garden had a two-year love affair; and it was rumoured that Mary had a similar relationship with Claude Debussy.

Marie-Agnès, do you still have that photo of Irene Triesch as Salomé? Mary Garden’s Salomé provoked a minor scandal at the Manhattan Opera House in 1909; her Dance of the Seven Veils, although performed with exquisite taste, was highly erotic, leaving the gentlemen in the audience distinctly hot under the collars of their fine evening clothes! Mary’s career in the USA – she worked almost exclusively in opera – brought her also – brought her also to Boston, with many years at Chicago.

There was, perhaps, a streak of ruthlessness in Mary Garden’s makeup; she has been described as ‘an archetypal diva who knew exactly how to get her own way‘ (Wikipedia).

Dr Michael Turnbull of Edinburgh has written an excellent biography of the Scots-American operatic soprano: Mary Garden (Michael T R B Turnbull, Scolar Press, 1997, ISBN 1859282636, 234x156mm – also published in North America.)

The last years of Mary Garden’s long life were unhappy. Never having married, she did not have the consolation of family life; and the friends of her youth had died. It’s thought that, from as early as 1945, she suffered progressively from dementia, causing distress to those around her. Few recordings exist that do justice to her beautiful voice. Yet we remember her.

Joseph Hislop first moved to the Swedish city of Gothenburg to study advanced colour-printing techniques; but soon his fine voice led to an international career. He sang Grand Opera with outstanding success at Covent Garden, London; La Scala, Milan; the Chicago Opera House, and the Royal Opera House, Stockholm (where he was decorated by the King of Sweden). During the 1924 season at Covent Garden, Hislop appeared with Melba, and his performance in the title rôle in Faust to Chaliapine’s Mephistofeles (1928) was memorable.

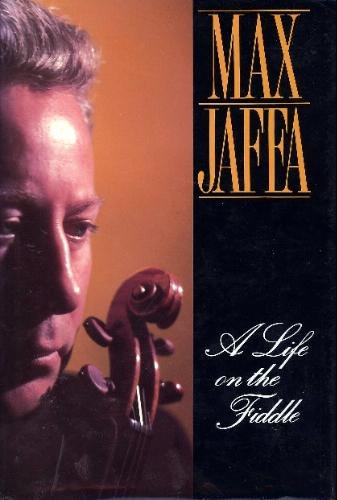

Hislop’s singing in opera combined rare lyric beauty with dramatic intensity, but he tackled lighter material too. The autobiography of the virtuoso violinist Max Jaffa (1911-91) includes a delightful account of a concert tour of Scotland that he undertook in the 1930’s, with Marie Gluck and Joseph Hislop as the principal singers. See A Life on the Fiddle (Max Jaffa, Hodder & Stoughton, 1991, ISBN 0340423811).

“In 1934 I had another opportunity to gain experience north of the border. I was asked to join a concert tour with Joseph Hislop, at that time Scotland’s most famous tenor, known as ‘The Scottish Caruso’. He was then 50 years of age, and I think he must have been winding down on the opera stage and had decided to remind the folks back home that he was still a voice to be reckoned with in concert.

“There were some 13 stops. We started with a week of concerts just north of the border, then travelled up to the Highlands for another five, before finishing in Edinburgh at the end of the month.”

How lucky were the residents of some of Scotland’s smaller towns, to be able to enjoy music of such quality! But those were the days before TV, and a time when so much more of life could be lived at first hand.

“People expected variety on a night out. They certainly got it with Hislop’s programme, which was a clever piece of dramatic planning! The evening started, quite soberly, with pianist Alfred Roth playing some Chopin, which was followed by an operatic aria or two from Verdi’s ‘La Traviata’ sung by the guest singer, Marie Gluck, ‘Soprano, from the Italian Opera Houses’ as her billing went.

“Then it was the turn of Max Jaffa (the writer!) to play the slow movement and finale of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto. Now, the last movement does whip up the tempo – and, of course, it raised expectations for the star of the evening, who then came on to sing a group of arias ranging from Handel to Verdi, including several of the favourites.

“For his second group, Hislop pulled out all the Scottish stops, with songs like ‘Bonnie George Campbell’ and ‘My Love, She’s But a Lassie Yet’. But there was more to come: for the climax of the evening, Hislop brought back Marie Gluck, and they performed the end of Act One of Puccini’s ‘La Bohème’ – from ‘Your Tiny Hand is Frozen’, right through to the passionate duet which the lovers-to-be sing as they walk off stage.

“Hislop proudly informed everyone that Puccini himself had told him he was the best Rodolfo he had ever heard.”

This lovely story is illustrated by a photograph of the little concert party – including Hislop’s manager, Captain Illingworth – standing in front of the enormous Rolls-Royce limousine, with liveried chauffeur, that was used to carry them around. In his later days, Hislop taught extensively, his most illustrious pupil being the great Jussi Björling (1911-60).

Dr Turnbull has also produced a comprehensive biography of Hislop: Joseph Hislop – Gran Tenore (Michael T R B Turnbull, Scolar Press, 1992, 234x156mm, ISBN 0859678938) An excellent book, which I recommend, although it has become rather expensive on the secondhand market.

Et voilà! – There we are; two opera stars and an enigmatic pianist! I’ve called Lamond enigmatic, simply because there’s so much about his long life that I don’t know; but I think I would have liked the man very much, if I’d ever been fortunate enough to meet him. His honesty, his forthright manner, whether in playing or in conversation; his love – I’d guess – of a good argument!

Lamond, Garden, Hislop, McCormack – all of these accomplished artists understood the universalism of music, the power of great art to transcend differences of politics, nationality or religion. John McCormack was devoted to his Church, which honoured him for his untiring charitable work; but there was nothing narrow in his religion, for his catholicism was ecumenical and international. Nor did John see why the fact that he’d taken American citizenship should prevent him from being elected as President of the Republic of Ireland! He was a citizen of the world.

Today, the memory of Frederic Lamond is honoured in the Scottish International Piano Competition, organised each three years – and over a period of 12 days – under the auspices of our élite music school in Glasgow, The Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. How Dr Lamond would have loved that word International! The first prize, won in 2010 by Oxana Shevchenko, included the Frederic Lamond Gold Medal, the sum of £10,000, a magnificent Blüthner grand piano and a recording contract.

Ultimately, as history has shown, even totalitarian states pass away; while the music of the immortal composers – Handel, Beethoven, Mozart, Chopin, Liszt – will live for all time in the hearts of men, and the work of their most distinguished interpreters remain ever fresh in our memories.

A bientôt, Marie-Agnès, Jean-Claude et Janice!

Iain.

This was great watching the videos and I was familiar with Frederic Lamond a great pianist from Scotland who was the primary authority on Beethoven’s music.

Hello Jason –

Thank you for your kind words and for your interest in our website. Although I don’t play golf myself, the game has a special place in the hearts of many Scots. (Have you read our post on this, ‘First Days of Golf’?)

Marie-Agnès, Janice and Jean-Claude will confirm to you that I have a weakness for jokes and funny stories! Now, just as all of the energy a player may give to a stroke in golf does not necessarily reach the ball – generally because his ‘swing’ is incorrect – in the same way, there were moments during the more ‘titanic’ passages of Beethoven when Lamond (and the great Master himself) struggled to get as much sound from the piano as he would have wished! No matter how hard the keys were hit, there was an absolute limit to the loudness produced.

I’d guess that the best modern concert instruments are now greatly improved in this respect; how does their ‘dynamic range’ compare with that of older pianos, I wonder? Perhaps one of our readers would be good enough to post a Comment on this?

All best wishes from the team at Scotiana!

Iain.

When I was eleven, the precursor of the Arts Council (the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts) brought Jack Wight Henderson, the future head of the piano at the then Scottish National Academy of Music, to our Stirlingshire village. I was duly presented as the village piano player and Henderson said he would like to have me as a pupil at the Junior Academy. I was made to play, in an audition situation I suppose, in the main hall of the academy in the presence of a very old man, dressed in black sitting in the far corner of the room. He was obviously important person and in my very casual way I don’t even remember if I shook his hand, but I strongly suspect he was indeed Frederic Lamond.

I did not have nearly enough talent to perform in public, apart from occasions at school, and remained more of a dilettante piano player for the rest of my life.

However, I was also interested in singing and good enough to get a Choral Scholarship to St John’s College Cambridge following my audition in King’s College chapel before the demanding Boris Ord and the more congenial Robin Orr. I continued singing as a paying hobby for many years, sometimes in the chorus at Covent Garden and with the BBC Singers. I look private lessons with teachers, really too good for me, including Roy Henderson, the principal teacher of Kethleen Ferrier. I also had a few with Joseph Hislop, then in his eighties. At his lessons, much of the time was spent listening to his delightful stories of events from his time at the Paris Opera.

Hello, Mr McGlashan –

Thank you for your most interesting Comment, and for taking the time to write at such length. It’s very pleasing to us to come across someone with personal memories of both Frederic Lamond and Joseph Hislop.

You mention also the splendid contralto Kathleen Ferrier, who remains one of my favourites, especially in oratorio. Our younger readers may be interested to know that 2012 was the centenary year of her birth at Higher Walton, Lancashire. Miss Ferrier came late to singing, her earliest musical success having been achieved as a pianist. Tragically, her life was cut short by cancer just as she was attaining the peak of her powers, but in those few years she had become one of the most-loved English singers.

In common with so many of the ‘greats’, Kathleen Ferrier had a strong vocal identity. Her voice – warm, unmistakable – was instantly recognised. As was said at her memorial service, ‘It seemed to bring to us a radiance from another world.’

With kind regards from the team at Scotiana,

Iain.

The 10th Scottish International Piano Competition will be held in Glasgow, 11-22 June 2014. (Entry is restricted to those under 30.)

Adjudication will be by an international Jury, chaired by Prof. Aaron Shorr, head of Keyboard Studies at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland (RCS).

Preliminary rounds will be held at the Conservatoire. Tickets may be obtained from the RCS Box Office.

The finalists can be heard – with Orchestra – in the Glasgow Royal Concert Hall on Sunday, 22 June. Tickets for this exciting event can be had from the Concert Hall Box Office.

For fuller details, see: http://www.sipc2014.org/tickets.html

Iain.

Back in the 1960’s I was a pupil of Agnes Walker when she lived in Thankerton, south of Lanark. During her instruction, Ms. Walker often spoke about her own piano teacher, Frederic Lamond. On a number of occasions, she showed me Lamond’s copy of the Beethoven Sonata’s, bearing Lamond’s pencil marked phrasing. I attended a couple of her concerts – one at the BBC on Queen Margaret Drive in GLasgow, and another at Stirling.

I later emigrated to Canada. Recently, I was listening to a program on the radio (the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) about Victor Borge, the famous pianist / comedian. Borge spoke about going to Berlin from his home in Copenhagen prior to WW2 to take piano lessons…from Frederic Lamond.

Prior to this program, I had not been aware of Borge’s relationship with Lamond

THought you might be interested.

John AItken

Regina, Saskatchewan

Thank you for your interesting Comment, Mr. Aitken, and for writing to us here at Scotiana. Did you go on to make a career in music, I wonder, or was the piano for you destined to be a leisure-time interest?

In the course of the limited enquiries I was able to make on Dr. Lamond, I was never able to discover how it was that the nursing-home in which the great pianist died came to be at Bridge of Allan, by Stirling. It would be wonderful if you could shed any light on this – was it simply the case, I wonder, that Lamond or his wife had friends or family in that area?

I’ve just been looking at the Wikipedia entry on Victor Borge – isn’t ‘Wiki’ a splendid resource? Yes, Borge was a wonderfully talented man, who died happily in his sleep after a long life! Courageous too, for Victor Borge, who was Jewish, travelled back in disguise to Nazi-occupied Denmark during the War to visit his Mother, who was terminally ill.

Kind regards to you all from Scotland!

Iain.