Hello Bonjour Dear Readers!

Before diving into today’s topic, I’d like to extend a special ‘thank you’ to my dear friend Iain from Scotland. He brought to my attention the fascinating story of a totem pole making its way back to Canada after nearly a century in Edinburgh.

Iain, your thoughtful sharing of this story has not only enriched my understanding of the complexities involved in the return of cultural artifacts, but it has also led to the creation of this blog post. 🙂

It’s astonishing to think that the Royal Canadian Air Force will be tasked with transporting this significant artifact across the Atlantic and possibly all the way to the West Coast! Quite a journey for a totem pole that has spent almost 100 years in Scotland.

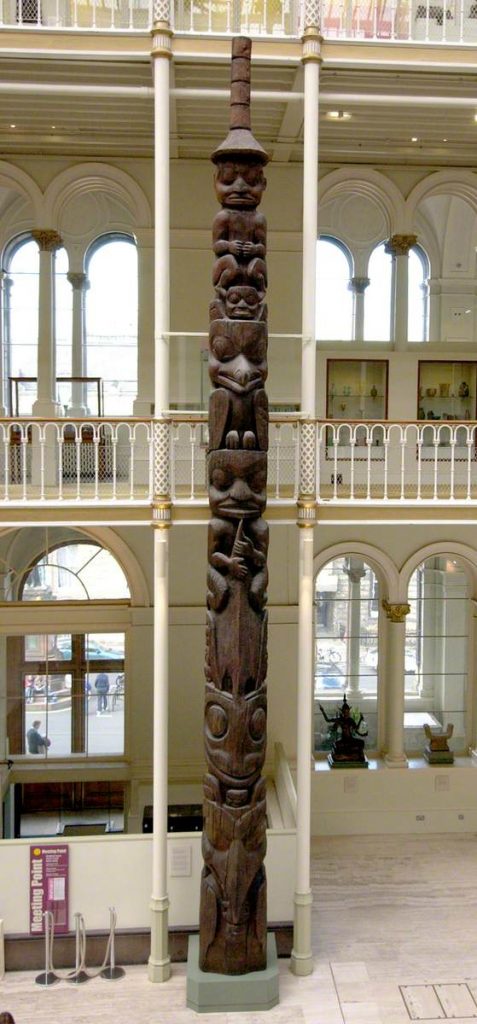

A culturally and spiritually significant 36-foot totem pole is set to make a 4,200-mile journey from the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh back to its original home with the Nisga’a Nation in British Columbia, Canada.

Following my ‘googling’ about the subject, I realize that the repatriation of totem poles and other indigenous cultural artifacts has been an ongoing discussion among museums, governments, and indigenous communities. However, specific instances of totem poles being returned from international museums back to their indigenous communities are not widespread and well-documented in the public record.

The return of cultural artifacts often happens in the broader context of repatriation movements, which may include human remains, sacred objects, and other forms of cultural property. Institutions like the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the British Museum in London have been involved in dialogues around the repatriation of indigenous artifacts, but these have not been limited to totem poles.

Repatriation can be a complex and lengthy process involving legal, ethical, and diplomatic negotiations.

Therefore, each case is unique and often makes headlines due to its significance for the involved parties as this one did!

*Here’s a summary of the full article featured on BBC webzine:

Crafted from red cedar in 1855, the totem pole originally stood in Ank’idaa village on the banks of the Nass River.

It was brought to Scotland in 1929 after being sold to the museum by Canadian anthropologist Marius Barbeau.

However, it was later revealed that the individual who sold the pole to Barbeau did not have the authority to do so on behalf of the Nisga’a Nation.

The intricately carved totem features animals, human figures, and family crests and tells the story of a Nisga’a warrior who was next in line to become chief before his untimely death.

Dr. Amy Parent, who holds the Canada research chair in indigenous education and governance at Simon Fraser University and goes by the Nisga’a cultural name Noxs Ts’aawit, has spearheaded the initiative to return the pole.

She explains that the totem has two carved ravens, among other animals, and a chief figure sitting at the top, each element adding layers of cultural and spiritual meaning to the Nisga’a people.

Last year, it was agreed that the totem pole should be returned to its rightful home, marking a significant step in correcting historical wrongs and acknowledging the rich cultural heritage of the Nisga’a Nation.

Sim’oogit Ni’isjoohl (Chief Earl Stephens) and Noxs Ts’aawit (Dr. Amy Parent) stand with the Ni’isjoohl memorial pole in the National Museum of Scotland on August 22, 2022. Photo Credit: Neil Hanna

As we contemplate the 4,200-mile journey this totem pole will undertake, it symbolizes a much larger journey toward justice and cultural reclamation. May this event encourage further dialogue and action in the realm of cultural repatriation, prompting us all to consider the artifacts that tell our collective human story and where they truly belong.

Interconnected issues of cultural heritage and repatriation

Scotland has its own complex history of cultural artifacts being taken abroad, though not necessarily totem poles. For instance, the debate over the Elgin Marbles, originally part of the Parthenon in Athens and currently held in the British Museum in London, has some similarities to the issue of repatriating cultural artifacts. While not Scottish per se, the case does involve the UK and has been a topic of debate in Scotland, especially when considering the broader conversation about the return of cultural property.

By Fernandopascullo (Own work), CC BY 3.0, commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3938217

Scotland itself has seen a push for the return of certain historical artifacts. For example, the Lewis Chessmen, 12th-century chess pieces discovered on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides but now mostly housed in the British Museum, have been the subject of calls for repatriation to Scotland.

The chessmen were discovered in early 1831 in a sand bank at the head of Uig Bay on the west coast of the Isle of Lewis, in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. There are various local stories concerning their arrival and modern discovery on Lewis.

Almost all of the pieces in the collection are carved from walrus ivory, with a few made instead from whale teeth.The 79[15] chess pieces consist of eight kings, eight queens, 16 bishops, 15 knights, 13 rooks (after the 2019 discovery) and 19 pawns.

Moreover, Scotland’s own Stone of Destiny, used for centuries in the coronation of Scottish kings, was taken by Edward I of England in 1296 and kept in Westminster Abbey. It was returned to Scotland in 1996 and is now in Edinburgh Castle.

On its return to Scotland, the Stone was prepared for its public appearance at Edinburgh Castle on St Andrews Day 1996. At this time the Stone was closely studied and recorded for the first time in its long history.

Personally, I am thrilled at the anticipation of re-visiting Edinburgh Castle in Scotland and take a close view of the Stone, when travel resume and it is safe to fly.

Until next, take care and all the very best,

Janice

Proud member of Scotiana’s team

~~~

Leave a Reply