Bonjour Marie-Agnès, Janice et Jean-Claude, Hello again from Scotland ! 🙂

I know that you rarely travel without your camera, Jean-Claude, but I wonder whether you were keenly interested in photography even as a schoolboy? One or two of my school friends would talk of developing and printing their own photos – in black and white only – skills that they had probably learned from their fathers. For this, a ‘darkroom’ was essential – perhaps just a large cupboard – where only a dim red light was permitted; it was a world of bottles, funnels and trays, with solutions of this and solutions of that, for all of the processes involved were chemical.

The coming of digital photography was nothing short of dramatic, very quickly replacing methods and materials that had been refined over a period of 150 years. And all of the advantages of digital photos – not least, the fact that they cost virtually nothing to take – seemed to coincide with the growth of the internet; so that now, high quality images appear to be all around us, and we could easily forget, I think, that it has not always been like this!

Kirriemuir Camera Obscura© 2007 Scotiana

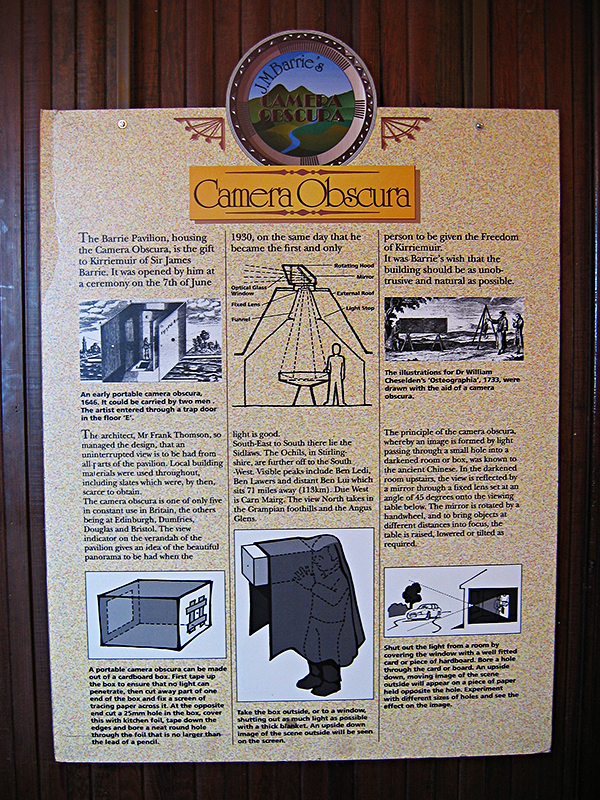

Janice, Marie-Agnès, Jean-Claude, did you happen to see the camera obscura when you visited Kirriemuir, birthplace of the dramatist and writer J M Barrie? Following the success in London of his plays – most famously Peter Pan – Barrie had become a wealthy man, and he gifted to Kirriemuir in 1930 a handsome cricket pavilion, in the upper part of which the camera obscura is situated. It’s one of only three in Scotland of which I’m aware – essentially a small, darkened room, into which light is admitted from a lens in the ceiling, throwing on to the screen below a magical picture of the scene outdoors.

Camera Obscura Kirriemuir Edinburgh Dumfries Scotiana montage © 2018 Scotiana

J M Barrie was brought up in Dumfries, where in 1836 a camera obscura had been installed in the tower of a disused windmill standing on high ground at the edge of the town – it still operates, and is now part of Dumfries Museum. Surely Barrie’s familiarity with the Dumfries camera obscura must have influenced his choice of gift to Kirriemuir, for otherwise we are faced with a really odd coincidence? Most visited of the three camerae – by far – must be the camera obscura in Castle Hill, Edinburgh, just along from the High Street.

Kirriemuir Camera Obscura © 2007 Scotiana

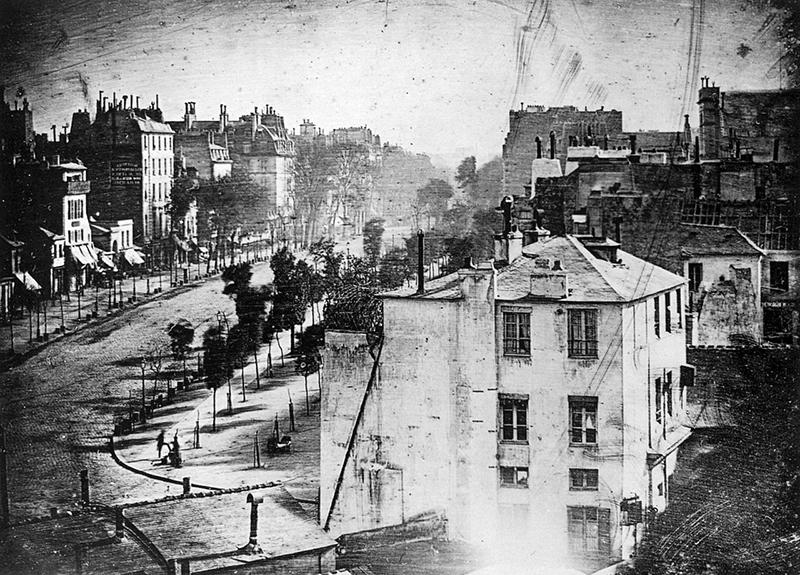

The principle of the camera obscura had been known for centuries, but how could its image be captured and preserved? The first faltering steps were taken by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (1765-1833) who in 1827 produced a Heliograph – a ‘sun picture’ – although it had required an exposure time of eight hours. Unfortunately, these images faded in time. In the last years of his life, Niepce worked with Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851), whose revolutionary Daguerrotype process was announced to the world in August 1839.

Point de vue du Gras by Niepce – earliest surviving photograph using a camera obscura

Boulevard du Temple Paris Daguerreotype Louis Daguerre 1838

This was the true start of photography, for Daguerre’s images were permanent, sharp and well-defined. The process was expensive and laborious, and required the handling of dangerous materials, but the finished Daguerrotype was a fine photograph of the highest quality. Nine separate steps could be identified in its making; the final, delicate image was produced on a thin copper plate, coated in silver and polished until it shone like a mirror. A skilled artist could then add colour, the dry pigments being held in place by some sort of adhesive. Lastly, the image was protected under glass. To this day a certain romance attaches to the Daguerrotype, and not only because many of the surviving examples portray beautiful women!

Composite photograph of David Octavius Hill (left) circa 1845, and Robert Adamson (right) circa 1845

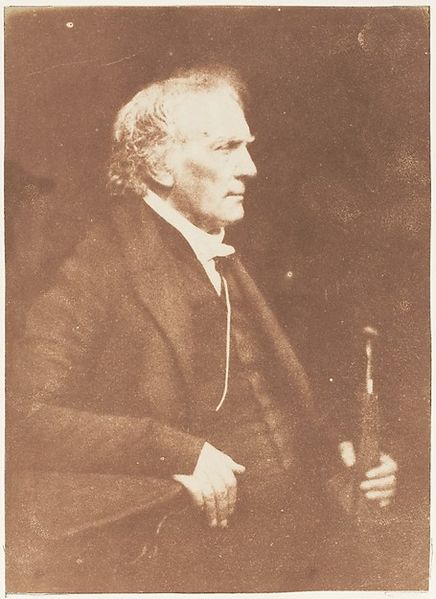

So, there we are, Chers Amis – the first inventors of photography were French, and we had always been told that the Scots invented everything! 🙂 Where do our pioneers, David Octavius Hill (1802-1870) and Robert Adamson (1821-1848) fit into the picture? To begin with, they used the later Calotype process (Greek, ‘beautiful impression’ ), introduced in 1841 by the English polymath William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877). While the achievement of Hill and Adamson was astonishing – they produced in their partnership of less than five years a total of several thousand high-quality pictures, refining their methods in the light of experience – yet neither man was responsible for any major technical innovation.

William Henry Fox Talbot in 1844.

Talbot was much more than the usual ‘gentleman amateur’. (Contrary to what is often written, he did not sign himself ‘Fox Talbot’.) He was born to wealth and privilege, inheriting the Lacock Estate near Chippenham, Wiltshire (since 1944, a National Trust property). Erudite and energetic, his interests ranged from the Classics to mathematics, from archaeology to the physical sciences, and he published work in all of these fields. We might well describe him as a nineteenth-century Renaissance Man! (I’d love to read a comprehensive biography of William Talbot – it would run to many pages.)

Lacock Abbey view from south photo by Jurgen Matern -Wikipedia

Lacock Abbey The internal courtyard of the cloisters Wikipedia

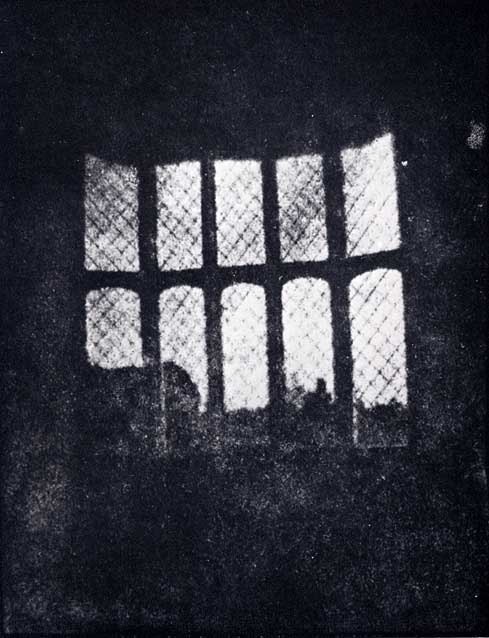

The home of the English inventor of the Calotype (or Talbotype) was named Lacock Abbey, for it stood on the foundations of 13th-century monastic buildings. Talbot’s most famous photograph, recognised around the world, is of the leaded glass in one of the Abbey’s tall windows. It is said that Talbot was in the habit of leaving some of his cameras – small varnished wooden boxes – lying about the rooms of the large house; ‘mouse-traps’ his wife called them! (We hope that he also employed a cat.)

A latticed window in Lacock Abbey photographed by William Fox Talbot in 1835

By all accounts Talbot was quiet and reserved in his manner. He had a wide circle of friends and was a prolific letter-writer; perhaps this was his preferred mode of communication. (A joint project between De Montford University, Leicester and the University of Glasgow aims to catalogue and study the Correspondence of William Henry Fox Talbot – to date, over 2,000 of his letters are known to have survived.) Within Talbot’s circle was Sir David Brewster (1781-1868), the Scottish man of science who in 1838 had become Principal of the united colleges at the University of St Andrews; Brewster was especially interested in optics and the possibility of photography, and Talbot kept him informed of his work.

David Brewster (11 December 1781 – 10 February 1868)

Sir David Brewster is of direct importance in the Hill and Adamson story, for while Talbot decided to protect his Calotype invention in England by means of a patent, it was on Brewster’s advice that this was not done in Scotland. (Brewster and Hill were already friends, but was there more to the question than that?) And we must note that it was Brewster, too, who would in due course introduce Hill and Adamson to each other, allowing their fruitful partnership to begin. Talbot had spent huge sums of money on developing his photographic process, and considered it fair that anyone exploiting it commercially should pay him a royalty; Henry Collen (1797-1879), the first calotypist in London, handed over 30% of his takings. On the face of it, Hill and Adamson, paying no royalty or commission, would enjoy a considerable advantage.

Although forever associated with Edinburgh, neither man was a native of the city. David Octavius Hill, born in Perth, first came to the Capital to work for the publisher, William Blackwood, and to study lithography. But his achievements in art and painting were to be considerable. Robert Adamson, one of a family of 10 children, was from Burnside in Fife, where his parents were farmers. Academically able, he excelled in mathematics and prepared for a career in engineering; but his health was never robust, so he was happy soon to explore instead the fascinating new area of photography, a subject to which he had been introduced by his brother, John, a doctor of medicine. It may well be that Robert Adamson had suffered from the effects of tuberculosis from an early age, the disease from which he would die before reaching his 27th birthday.

St_Andrews,_North_Street,_Fishergate,_Women_and_Children_Baiting_the_Line

Dr John Adamson (1809-1870), Robert’s senior by 12 years, had practised and refined the Calotype from the earliest days. The portrait that he made of their sister, Melville, in 1841, was in fact the first photograph produced in Scotland by Talbot’s process. John Adamson had achieved a high level of skill in a matter of months, and he taught his brother well. The town of St Andrews is perhaps the most important in the early history of Scottish photography, for Dr John Adamson was based there, as well as Sir David Brewster and other significant figures.

Edinburgh night panorama from Calton Hill Wikipedia

Dugald Monument Calton Hill Edinburgh © 2007 Scotiana

Rock House Calton Hill Edinburgh

Robert Adamson moved to Edinburgh in May 1843, at a time when half-a-dozen producers of Daguerrotypes were already active there. He established his studio at Rock House, Calton Hill, just below the monument to Dugald Stewart (1753-1828). (In the style of a Greek temple, this elaborate memorial by Playfair to the Scottish Enlightenment figure is one of the city’s most familiar landmarks.) In just four weeks’ time, the working partnership between Robert Adamson and David Octavius Hill was destined to begin.

Edinburgh St Andrew’s Church George Street

To our modern eyes, the event that brought them together may seem strange – a dispute between rival groups within the Church of Scotland; but in the 1840’s, when religious observance was almost universal, this was a matter of high importance. For decades, the Church had been embroiled in legal disputes concerning its governance, and matters were coming to a head. And so it was that on 18 May 1843 about 200 ministers and elders dramatically walked out of the Church’s General Assembly – its annual ‘parliament’ – being held in Edinburgh at St Andrew’s Church, George Street, and made their way in procession down Dundas Street to Tanfield Hall, Canonmills.

David Octavius Hill and Sir David Brewster were both present that day, and could not fail to have been moved by the events they witnessed. Hill was in awe of the determination and moral courage of these men, who at great personal cost – for they would lose their stipends, homes and places of worship – were resolved to found a new Church, the Free Church of Scotland. By 23 May, a total of 474 ministers had signed the Deed of Demission at Tanfield Hall, reducing by about one third the number of clergy and of congregations remaining within the Church of Scotland. (By 1929, the majority of Free Church congregations had become reconciled with the Church of Scotland, and re-united with it; today’s smaller Free Church of Scotland, its membership concentrated in the Gaelic-speaking areas, is composed of congregations which chose to remain independent.)

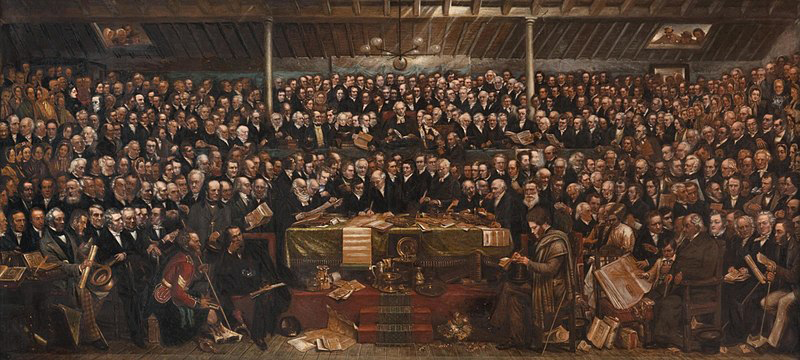

David Octavius Hill painting of the 1843 Disruption forming Free Kirk

Conscious of the historic importance of this great schism in the Established Church, generally referred to as the Disruption of 1843, Hill resolved to create a huge painting that would incorporate a likeness of each of the dissenting ministers. But how on earth was he to capture an image of as many as possible of these hundreds of men, before they dispersed from Edinburgh to return to their families? Photography was the answer, suggested Brewster, and young Robert Adamson was the best man to help. By 9 June, the partnership of Hill and Adamson had effectively begun – and to Robert Adamson, it must have been a comfort to see the prospect of much profitable work, so soon after all the expense of setting himself up in business.

Rev Thomas Chalmers (1780-1847) by Hill and Adamson

For the sake of speed, the ministers were sometimes photographed in groups of 20 or 25 at a time; but Hill and Adamson also produced high-quality portraits of individual men, such as Rev Thomas Chalmers (1780-1847). From the start, it was the intention of the Edinburgh pioneers that each of their portraits should have the quality of a work of art.

Another of those Victorian ‘polymaths’, Dr Chalmers excelled in mathematics, trigonometry, chemistry and economics, yet it was as a preacher that he was licensed – quite exceptionally – at the age of 19. Described as possessing ‘rare and singular qualities’ and speaking with ‘a rich and glowing eloquence’, he has been held to be Scotland’s greatest 19th Century churchman. On that fateful Thursday of the Disruption, Thomas Chalmers followed the retiring Moderator out of the door of St Andrew’s Church in George Street, and was elected just an hour later as first Moderator of the new Free Church of Scotland.

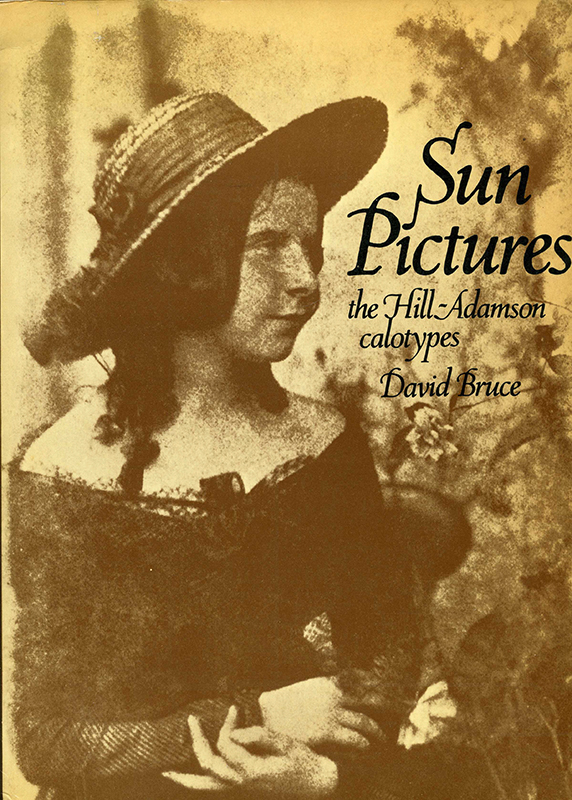

Sun Pictures The Hill-Adamson calotypes David Bruce

A clear majority of Hill and Adamson’s Calotypes were portraits, and it’s probably not too soon to mention the difficulties involved, from the points of view of both the photographers and the sitter. The biggest single problem was the need for sunlight – preferably bright sunlight – and the length of exposure required. We have the words of Sir David Brewster on this, writing in the Edinburgh Review of January 1843: In the light of a summer sun, from ten to fifty seconds will be sufficient; but when the sun is not strong, two or three minutes in summer is necessary. To set the exposure time, the camera’s lens cap was simply removed and replaced as required.

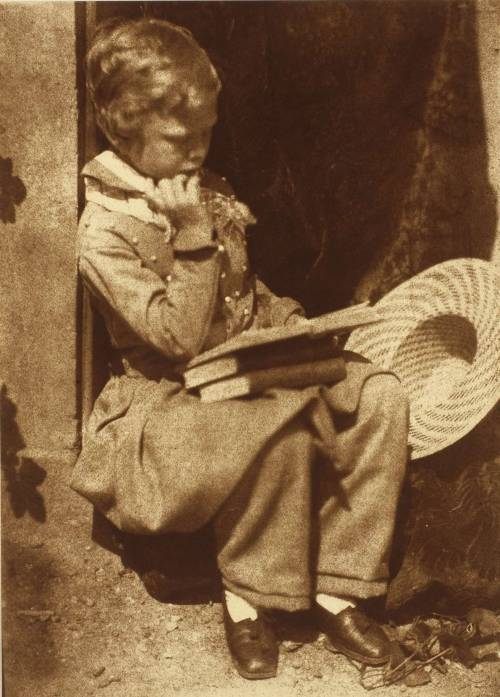

Master Grierson by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson c. 1843-1847 © Scottish National Portrait Gallery

Ensuring that the sitter moved as little as possible during the exposure also caused Hill and Adamson many headaches, and they resorted to various clever stratagems to deal with this problem. Marie-Agnès, Janice, I wonder if you recall a photograph I mentioned, showing a little boy seated at the doorstep of his home, and apparently reading? Two large books had been placed on his lap, while on top a third lies open, helping to light the boy’s face. His arm rests on the open pages, supporting his head and minimising any movement. Very well planned, indeed!

‘His Faither’s Breeks’© Scottish National Portrait Gallery

In another picture – by way of a joke – a boy from the nearby fishing port of Newhaven is photographed while dressed up in his father’s work trousers; no doubt, he would soon go to sea himself. ‘His Faither’s Breeks’ is the title; even with the legs rolled up, the garment is much too big. Hill and Adamson made many photos of the Newhaven fisherfolk; they understood the hard and dangerous work they did, and that part of the price of fish was paid in men’s lives.

Hugh Miller, photographed by Hill & Adamson, circa 1843–1847.

More typically, though, Hill and Adamson’s portraits were of mature men who had reached a certain station in life – Professor John Wilson (‘Christopher North’) (1785-1854), academic and prolific contributor to Blackwood’s Magazine; John Henning (1771-1851), sculptor; John Blackie (1805-1873), the Glasgow publisher; Hugh Miller (1802-1856), geologist and writer. Personal friends were, of course, photographed too – Sir David Brewster (1781-1868) and his wife Lady Juliet (1786-1850). The portrait of Miss Mary McCandlish, in her broad-brimmed hat, must now be one of the best-known images of the Edinburgh calotypists; Hill and Adamson turned out so many pictures that we still find appealing.

David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson – The Scott Monument, Edinburgh – Google Art Project

By 1843 the Scott Monument in Princes Street was already under construction (Sir Walter having died in 1832); Hill and Adamson photographed it at this half-way stage, and again on its completion two years later. Similarly, other Edinburgh monuments were captured for posterity; John Knox’s House in the High Street is a striking example.

View of High Street Edinburgh c. 1845 by David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson

What was the contribution of each man to this outstandingly successful partnership? We cannot know this with certainty, but there are some clues – David Octavius Hill was an outgoing, sociable man with a wide circle of friends in the artistic world of Edinburgh and beyond, and was able to bring large numbers of clients to the new business. He also had a talent for making his sitters feel at ease, contributing to the ‘natural’ look of the finished portraits.

We’re told that Robert Adamson was extremely protective of the secret methods he employed, and conscientious to a fault in repeating again and again some of the tiresome processes. And Hill is known to have praised Adamson’s technical expertise, saying that it was far above that of other photographers. But the partnership ended as suddenly as it had begun. Sadly, Robert Adamson – not yet 27 – became gravely ill with tuberculosis, dying on 14 January 1848. It’s quite remarkable, I think, that those two men captured so many high quality images – work that we continue to admire – at a time when photography was only beginning to find its feet.

A bientôt!

Iain.

Passing through St Andrews, we happened to park close to an elegant restaurant in South Street called ‘The Adamson’. A plaque informed us that from 1848 to 1865 the home of Dr John Adamson – photo pioneer and teacher of Robert Adamson – had been here. St Andrews has had no better friend than Dr John Adamson; he was devoted to the town, a Councillor, philanthropist and champion of public health.

Every second building, it seems, has a plaque relating to some interesting part of its history; there’s so much to see in a short walk around the centre.

Iain.