Robert Burns : Our Poet at Ellisland Farm, 1788-1791 ..

.

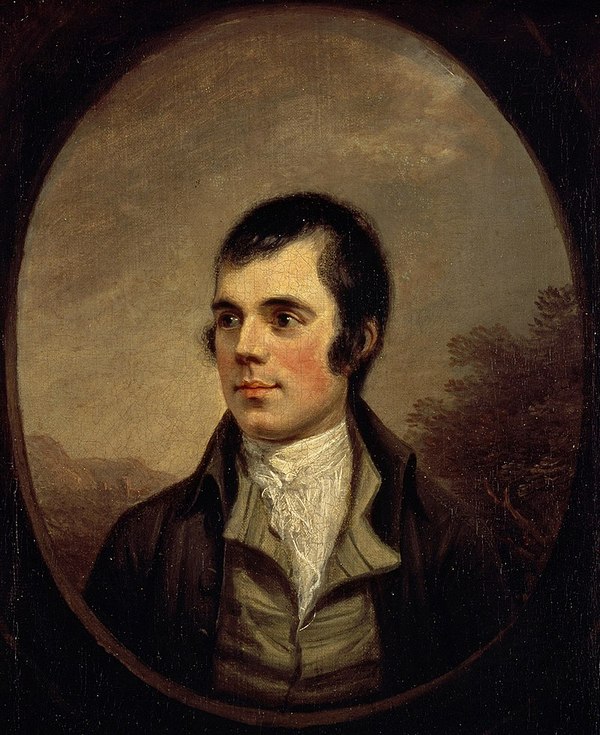

Portrait of Robert Burns by Alexander Nasmyth, 1787, Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

Bonjour Janice, Marie-Agnes et Jean-Claude. Hello again from Scotland ! 🙂 We do hope that you’re all keeping safe.

Margaret and I were very happy, Marie-Agnes, to receive a message from you just a few days ago, saying how much you liked the Burns poem “in English” that we’d sent you, and for that matter how much you liked the Poet too, a kind-hearted man and a humanitarian, as well as a Scottish patriot! We’re sure that everyone on Scotiana’s mailing list now realises that you and Jean-Claude are French, although you write so nicely in English, as does our webmaster, Janice, who lives close to Quebec in the French-speaking part of Canada! 🙂

I try to choose, if possible, subjects with an international connection, when deciding what to write about in these Letters from Scotland – my plan is that each should be in the style of a letter to friends, yet one that is shared with readers of Scotiana, wherever they happen to be. Now, could any subject, I wonder, have a wider appeal than Robert Burns (1759- 1796), who has been called ‘the poet of all humanity’?

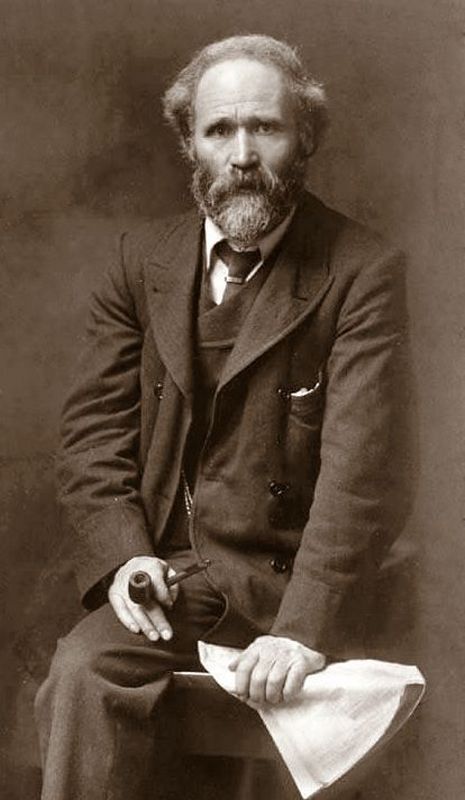

James Keir Hardie by John Furley Lewis 1902

In his ‘political’ poems, Burns’ genius was to give a voice to the weak and the dispossessed, in lines that have become immortal. He wrote of an ideal society, where human talents and the goodness in people’s hearts would count for more than wealth, titles or hereditary privilege. All men and women would matter. He called, too, for a brotherhood between the nations of the world, one of the strongest themes of the philosophical movement that we now call the Enlightenment – and all of this before the year 1800! Robert Burns’ contemporary, the German Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805), also wrote of universal brotherhood in his Ode to Joy, now the anthem of the European Union. I wonder, would James Keir Hardie (1856-1915) have achieved all that he did as founder of the Labour Party, without the influence of such writers as Burns, a hundred years before?

Friedrich von Schiller lithograph

Burns’ language is typically vigorous and robust, but can be exquisitely tender as the situation requires. He has been called the pre-eminent poet of Sympathy and of Sentiment. On lighter subjects, his choice of words is often just so clever that it makes us smile! Robert had the good fortune to be celebrated during his lifetime, although he never became rich. After his death, however, the poet’s reputation and renown increased to the point where what one might call a ‘cult’ of Burns almost developed, not unlike a kind of secular religion. His memory was revered, and fine bronze statues erected in their hundreds on every continent where Scots were to be found.

How does one account for this hero-worship? We should, I think, look for a clue to Burns’ many biographers, who found the life and character of the man himself as intriguing and interesting as anything he ever wrote. Some, of course, were critical, and some quite unjust. But at the end, we see that the poet was a fair-minded man, humane and liberal in his outlook, hardworking and by no means irreligious – and that he was a fiercely patriotic Scot.

Ellisland Farm Auldgirth – Source Wikimedia

It was in the latter part of his short life that Burns came to Ellisland farm, just six miles north of Dumfries. You may not know, Dear Friends, that this beautifully-situated small property beside the River Nith has been held in trust for the people of Scotland for almost a hundred years, and that the current Trustees have made an urgent public appeal for help, for they face very serious financial difficulties. I shall return to this towards the end of my Letter, but I’m pleased to tell you that Margaret and I have both already made a contribution at the Just Giving page of the Robert Burns Ellisland Trust. 🙂

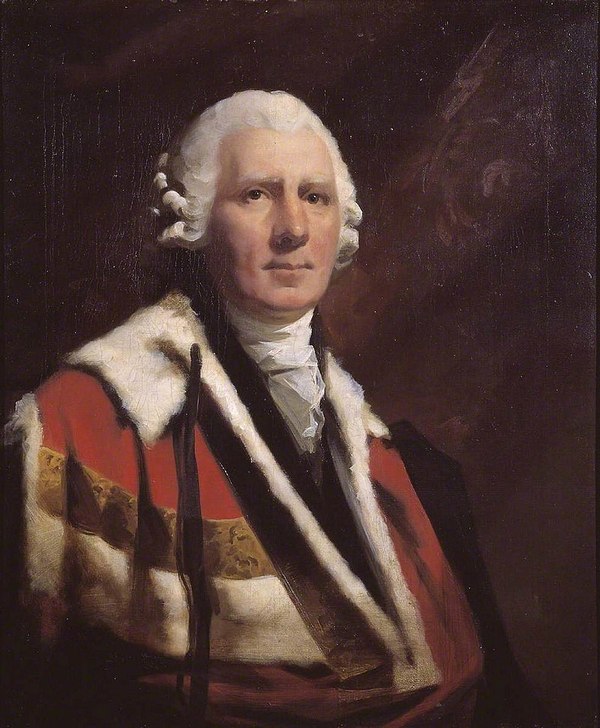

The 1st Viscount Melville by Henry Raeburn

Before we get to Ellisland, however, I’d like to sketch an outline of Robert’s earlier days, for it does seem to me that, sadly, knowledge of Burns has been allowed to decline, even here in Scotland. With determination, though, this tide can be turned! Chers Amis, to keep my Letter relatively short I shall avoid any account of Burns’ ‘private’ life – now so public! – and of his many sexual entanglements. For the moment, I shall say only that the poet appeared quite unable to help himself when in the presence of a pretty young woman, and that, knowing his own weakness, he really ought to have tried harder to stay away from danger. It was a recurring joke of his to complain that he had – once again – fallen victim to some ‘fair enslaver’! In Burns’ defence, it’s fair to point out, I think, that women clearly found him both handsome and attractive. Writing may be a solitary activity, but Robert was a sparkling conversationalist, a spell-binding talker! He was, in short, no ordinary man.

As a tenant farmer, Burns was denied any part in politics, yet he was courageous in saying and writing as much as he dared to begin to turn his readers’ minds towards our modern notion of democracy. It’s essential, I think, not to forget that in the poet’s day Scotland was governed virtually by a single individual, the all-powerful ‘benevolent despot’ Henry Dundas, Viscount Melville (1742-1811), who implemented north of the Border the will of ‘mad’ King George III. Was it any wonder, then, that Burns, a highly intelligent man, resented this unfairness, and that his heart glowed with pride for his native land?

Over 300 biographies

.

Broughton House library Kirdcudbright Dumfries & Galloway © 2015 Scotiana

A few days ago, Marie-Agnes, you mentioned having begun to read the long biography of Burns by the French academic Auguste Angellier (1848-1911). I think I first learnt of the existence of this book, completed in 1893, on seeing a copy at Broughton House, Kirkcudbright – for the artist Hornel (about whom you have written so much here at Scotiana!) was an admirer of Burns and had assembled a huge collection. Well over 300 full biographies of Scotland’s National Poet have been published. The earliest, by Dr James Currie, appeared in 1800 as part of a four-volume edition of the Works of Robert Burns – and it soon gained notoriety, for Currie depicted the poet as a hopeless drunkard. I don’t doubt for a moment that Currie’s prejudice stimulated others to set the record straight!

Several new Burns biographies came out in the early 1990’s, in anticipation of the bicentenary of the poet’s death that would fall in 1996. My own favourite is by the respected ‘Burnsian’ James Mackay (1936-2007) – whom you will already know, Janice, as the prolific writer on everything to do with the world of postage stamps! Mackay also had many years of Burns scholarship behind him, and had become a world authority on the poet. His book was tremendously well received when it first appeared in September 1992, for James Mackay had taken the trouble to verify every detail from original sources. The Saltire Society’s judging panel declared it to be the best Scottish book – in any genre – of 1993, and the University of Glasgow awarded to its author the honorary degree of Doctor of Letters (D.Litt) in recognition of the quality of his Burns work.

The edition that I have beside me is from September 2004, produced by Alloway Publishing and running to 749 pages. The type has been reset, I think, with minor corrections, but the text is substantially the same as in the original :

Burns : A Biography of Robert Burns – James Mackay. Alloway Publishing, Darvel, Ayrshire. 2004

ISBN 978 090 752 6858 (Hardback) ISBN 978 090 752 6865 (Paperback)

Alloway Publishing logo

Janice, Marie-Agnes, Jean-Claude, you probably already have some Alloway Publishing books on your shelves, and may recognise the imprint of this firm, for it depicts a wee field mouse munching on an ear of corn! 🙂 Stenlake Publishing, now at Catrine, acquired Alloway some years ago, inheriting at the same time a fairly large stock of Mackay’s Burns biographies in both Hardback and Paperback. Sadly, in recent years they had been selling only slowly, so Stenlake’s are now offering them at a reduced price – and with free postage within the UK – provided you order directly from their website. (Postage to Europe is only £2.60 per book. A bit more to cross the Atlantic, I would think, Janice!)

James Mackay dedicated this masterly work to his friends Lucie and Ross Roy of the USA. Prof George Ross Roy (1924- 2013), latterly of the University of South Carolina, was for many years the leading expert in North America on Burns and indeed on all of Scottish literature. He was born in Montreal, Canada, of Scottish ancestry, and wrote widely on our famous poet. I recall that, for those who might prefer a shorter first biography of Robert Burns, Ross Roy recommended Catherine Carswell’s book, which first came out in 1930. Mrs Carswell, of Glasgow, was primarily a novelist and may well have repeated one or two of the more common errors, but as far as I know her biography remains the only one written by a woman – and young women did play an important part in the life of Robert Burns! 🙂

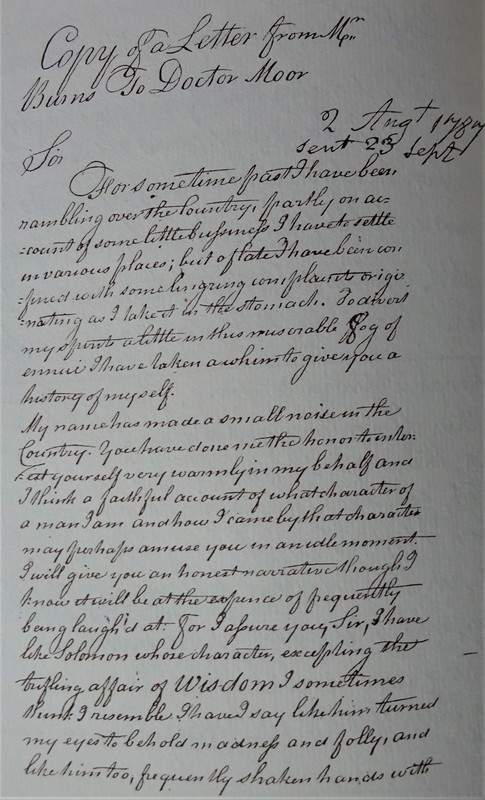

Robert Burns’s letter to Dr Moore. Glenriddell Manuscript

From Mossgiel Farm, Mauchline, Robert Burns wrote at length on 2 August 1787 to Dr John Moore (1729-1802), father of the legendary soldier Moore of Corunna, tracing the course of his life in considerable detail. (This letter, the ‘Autobiographical Letter’ as it has become known, has since the mid-1850’s been in the care of the British Museum, London, while a facsimile can be seen at the Burns Birthplace Museum, Alloway, by Ayr.) The poet was then 28 years of age and becoming known throughout Scotland, for an expanded edition of his Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect had appeared in Edinburgh just a few months earlier, on 17 April. The first printing of Burns’ poems – which Dr Moore had admired – had taken place at Kilmarnock on 31 July 1786. The tragedy is that, less than 10 years after these successes Robert would be dead. He never did grow old.

Burns’ early years, 1759-1784

.

Alloway Burns Cottage garden entrance © 2012 Scotiana

In this uniquely important letter, the poet tells how he and Gilbert (1760-1827) – 20 months his junior – left the Alloway cottage as small boys in 1766, together with their sisters Agnes (aged four) and Annabella (two years), moving just a short distance to Mount Oliphant Farm. The birth of William in 1767, John (1769) and Isobel (1771) completed the family. It’s a splendid tribute to their parents, I think, that all seven escaped the childhood diseases that were then so common. I don’t doubt that the relative isolation of the Burns family was an important factor, and one from which we all could learn as the Covid-19 pandemic continues! At Mount Oliphant, as a teenager, Robert ‘first committed the sin of rhyme’ – and was, even at 15, the chief labourer on the farm, his father’s health having broken down. It seems beyond doubt that this over-exertion at such a young age resulted in irreparable damage to Burns’ heart.

Lochlea_Farm-geograph.org.uk-3539

By 1777, when Robert was 18, the family were at Lochlea (or Lochlie) Farm, Tarbolton, but their fortune was scarcely improved. Traditional farming yielded little profit. James Mackay explains that during the Burns family’s time in agriculture the weather had been appalling, with heavy rain and frosts that persisted for months – a vitally important fact, and one that many writers simply fail to mention. The 1770’s and 1780’s lay at the end of what we now call the Little Ice Age, when all of Europe, if not all of the Northern Hemisphere, suffered unusually low temperatures.

Masonic_Penny._Robert_Burns’s_Lodge._Tarbolton_St_James._No.135

At 22, Robert was initiated into the ‘craft’ of Freemasonry at Lodge St David, Tarbolton. ‘Far gone in consumption’ – gravely ill with tuberculosis – the poet’s father died, aged 63, after seven years’ tenancy at Lochlea. He and his eldest son had had a spectacular row, from which their relationship may not have recovered. Robert, now a young man, had wished to join a dancing class – where girls would, of course, be present. His father absolutely forbade it, but Burns defied him. (It seems possible that the young poet had also disobeyed his father in this matter on an earlier occasion – at Mount Oliphant and while ‘in his 17th year’. Those girls! Robert enjoyed dancing and quickly became proficient.)

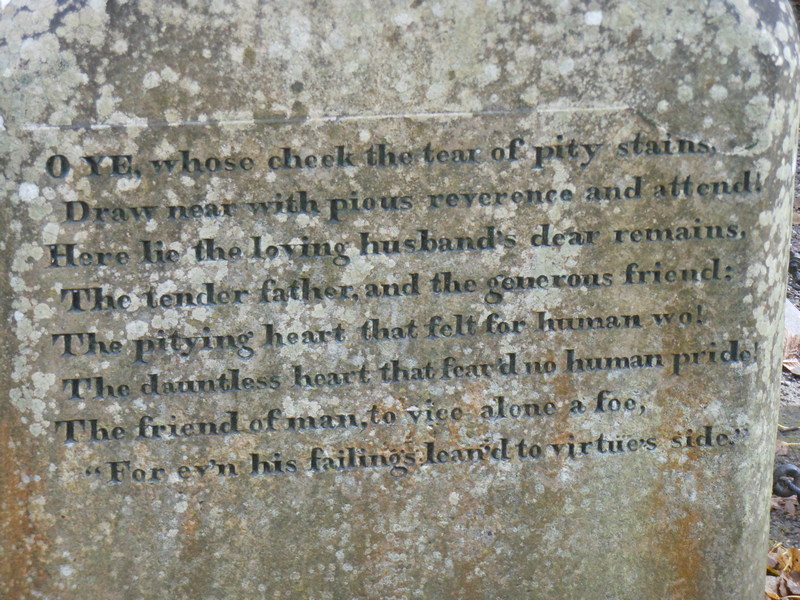

As is the Scottish way, such rows and disagreements, however bitter, remain private within the family. And so the epitaph that Burns composed for his father’s grave in the Old Kirkyard at Alloway was generous as well as eloquent :

Robert Burns’s epitaph for his father – Alloway Old Kirkyard © 2012 Scotiana

“O ye, whose cheek the tear of pity stains,

Draw near with pious rev’rence, and attend!

Here lie the loving husband’s dear remains,

The tender father, and the gen’rous friend;

The pitying heart that felt for human woe;

The dauntless heart that fear’d no human pride;

The friend of man – to vice alone a foe;

For ev’n his failings lean’d to vitue’s side.”

Burns, we’re told, had studied all of the English classical poets. His favourite was William Shenstone (1714-1763), although the quotation that he most admired was from Alexander Pope (1688-1744) : “An honest man’s the noblest work of God.” Robert Burns, strictly – perhaps too strictly – brought up, had from time to time contemplated his own behaviour and was conscious of falling short. But he had now reached his maturity as a poet.

Mossgiel, 1784-1786

.

Robert Burns Birthplace Museum Alloway Mousie sculpture © 2012 Scotiana

The year 1784 found Robert and Gilbert as joint tenants at Mossgiel, Mauchline. The practice in those days was to plough at the ‘back end’ of the year, so that the winter frosts would break up the soil, and it was at Mossgiel Farm that the incident occurred which led Burns to compose the poem that is one of my personal favourites : “To a Mouse, On Turning her up in her Nest with the Plough, November 1785.” The poet’s sympathy for this tiny ‘fellow mortal’ is quite astonishing. He clearly understands that the mouse suckles her young, just as a human mother does. And he allows that the little creature might be endowed with some level of intelligence – hence these lines, among the most-quoted in the English language :

The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men gang aft agley (often go wrong)

An’ lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain, For promis’d joy (leave us nothing)

Okay, a few Scottish dialect words are here, but their meaning is not too difficult to work out! 🙂 Perhaps the Scots dialect is primarily a spoken language, but to those who understand it, it is wonderfully expressive. James Mackay tells us that little poetry had been printed in the ‘Scots vernacular’ at that date, but Burns was confident of success if he were to publish his verses. He took the precaution, however, of first obtaining several hundred subscriptions to cover his outlays.

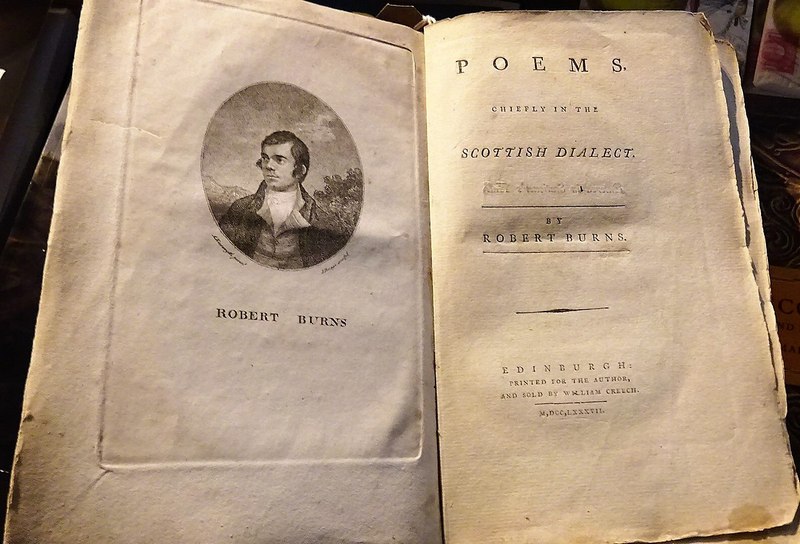

Kilmarnock edition of Robert Burns Poems – Source Burns Scotland

Robert approached John Wilson of Kilmarnock, owner of the only printing press in Ayrshire, and it was agreed that 612 copies of his book should be produced. It would have a stitched binding and 240 pages, enclosed in blue paper covers; and so the first edition of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect appeared on 31 July 1786. As each book sold for three shillings, Mackay estimates that its author would have earned from the project a little over £50. Burns postponed for the moment the plans he had made to emigrate to Jamaica, where he had been offered work as an under-manager on a sugar plantation – an enterprise which at that time still relied upon slave labour. (In anticipation of leaving Scotland, the young poet had made over his half-share in the Mossgiel tenancy to Gilbert just days earlier, on 22 July.)

Mossgiel Farm is within convenient walking distance of Mauchline. Although little more than a village in Burns’ day, the place had no fewer than 13 public houses; mild drunkenness was more easily tolerated before the coming of motor transport, and especially in the country areas. We’re told that Robert was only an occasional visitor to ‘Auld’ (Old) Nance Tinnock’s tavern. ‘Rob Mossgiel’, as he was known, set himself apart in dress and appearance, wearing his hair long and tied with a bow, while over his dull grey clothes he threw a plaid of golden brown.

Frances Anne Wallace Dunlop (1730-1818)

Robert Burns was soon famous throughout Ayrshire, and his book quickly sold out. Among those who bought several copies was Mrs Frances Dunlop (1730-1815) of Dunlop House, a wealthy landowner and heiress. Considerably older than the poet, she was destined to become a sort of ‘Mother Confessor’ to him, and his most regular correspondent. Much impressed by Burns’ work “The Cotter’s Saturday Night”, she despatched a servant to Mossgiel with a request for half-a-dozen copies of the poems and a kind invitation to their author to visit. Only five copies remained, but Burns was pleased to discover that Mrs Dunlop shared the name of his boyhood hero, William Wallace (C.1270-1305), and even more excited to find that she claimed descent directly from the brother of the valiant Guardian of Scotland! And so began a cordial friendship that would endure almost until the poet’s death.

Edinburgh, 1786-1788

William Creech – Scottish publisher, printer, bookseller and politician by Sir Henry Raeburn 1806

Four months later, having borrowed a pony, Burns set off for Edinburgh, where he planned to have a larger edition of his poems produced and would be able to supervise the work personally. As at Kilmarnock, a good number of subscriptions were obtained. William Creech (1745-1815), bookseller and publisher (and a later Lord Provost of Edinburgh) assisted in this. In total 3,000 copies were made, of 408 pages, although the last 60 or so pages listed the names of the hundreds of subscribers and included a glossary of Scots words. Robert then sold his copyright to Creech for 100 guineas (a guinea was 21 shillings). The books were bound by William Scott in French grey boards, the printing itself having been done by William Smellie (1740-1795) at Anchor Close, just off the High Street.

Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect by Robert Burns 1787 edition © Rosser 1954 on Wikimedia

.

William Smellie Scottish printer

.

Smellie was a man of particular note, for while his manners might have lacked something in refinement, he was extremely well educated and a veritable polymath. (He had in fact been the first editor of Encyclopedia Britannica, founded at Edinburgh in 1768. He compiled this large work in the space of three years and also contributed much of its content.) The Edinburgh Edition books were published on 17 April 1787 and sold for six shillings, subscribers paying one shilling less. Taking advantage of his new copyright, Creech brought out a two-volume edition in 1793 (reprinted 1794), in association with the London publisher, Thomas Cadell (1742-1802).

Robert Burns could hardly have come to Edinburgh at a more exciting time. The philosopher David Hume (1711-1776) had died, but such important figures as the economist Adam Smith (1723-1790) were still active, and the city continued to enjoy its Golden Age as one of the leading intellectual centres of Europe. Only with the passing in 1832 of the poet and novelist Sir Walter Scott (b.1771) – another of your favourites, Marie-Agnes! – would the glory of this illustrious period begin to fade.

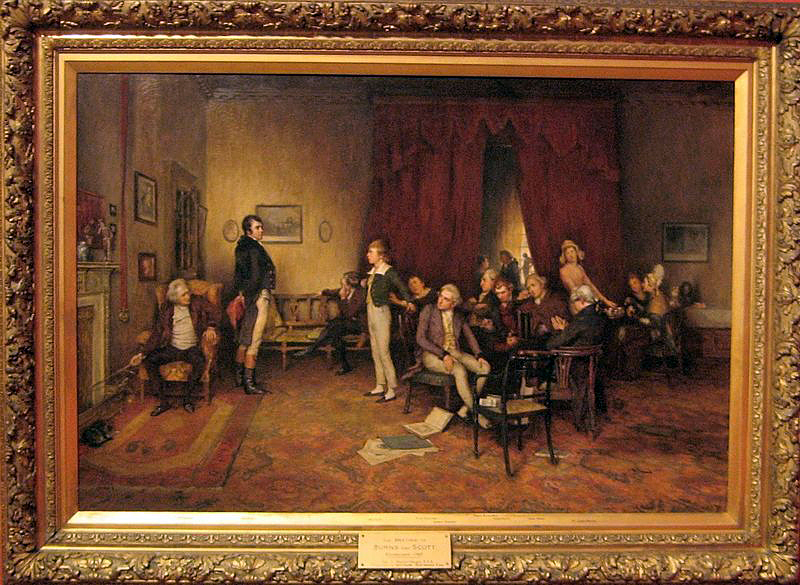

‘The Meeting of Burns and Scott’ – painting by Charles Hardie 1893 – Dunedin Public Art Gallery

Burns’ presence in Edinburgh caused quite a sensation. Everyone, it seemed, was curious to meet the famous poet, of humble birth and apparently little formal education, yet capable of genius. Such people as Mrs Dunlop and Dr Moore had large networks of friends, so that introduction followed introduction and one invitation led to another. Freemasonry, too, was an important social network. Burns was based in Edinburgh for about a year and a half altogether, although during this time he made long trips to the Scottish Borders (and into the north of England), to Stirlingshire and to the Highlands of Scotland, very often being accorded warm hospitality.

‘Clarinda’ and an impossible love

Clarinda’s grave Canongate Kirkyard Edinburgh © 2012 Scotiana

It was at an afternoon tea-party that Burns first crossed the path of Mrs Agnes McLehose (1758-1841), a fellow guest. Born in Glasgow, Nancy McLehose was a few months older than Robert, not tall, but blonde and very pretty. (I think that only silhouette portraits of her have survived.) They were immediately attracted and fell in love. Janice, Marie-Agnes, Jean-Claude, I did assure you that I’d say little of Burns’ sexual adventures, but no lesser an authority than James Mackay has been satisfied that the pair did not attain ultimate intimacy, so that’s good enough for me! 🙂

Clarinda’s Tearoom Canongate Edinburgh © 2012 Scotiana

Very soon after that first meeting in Edinburgh, Burns badly injured his leg in a coach accident, confining him to his quarters. As a married woman and a mother – although separated from her husband (who was not altogether admirable) – Nancy had to be discreet, so she and the poet conducted an intense love affair by post, sometimes writing twice a day. A talented woman, Nancy was well able to respond in verse; she was ‘Clarinda’ to his ‘Sylvander’ in their secret correspondence. They met only occasionally, but their situation was impossible. Nancy had deeply-held religious views and Burns himself was committed to another woman. They could not forget each other, however.

Clarinda’s Tearoom memorabilia Canongate Edinburgh © 2012 Scotiana

Falling in love with Clarinda had been the central event of Burns’ life, and in other circumstances the two might well have married. It’s pretty clear, too, that during the poet’s three years at Ellisland – even as he set up his new home – Nancy McLehose remained very much on his mind. His feelings for her were as strong as ever.

Burns and Nancy saw each other for the last time on 6 December 1791, just weeks after Robert had moved down to Dumfries with his family. Each gave the other a lock of hair as a keepsake. And on 27 December Burns sent Nancy a note, enclosing one of his most emotionally powerful poems, Ae Fond Kiss – ‘One Tender Kiss’.

Had we never lov’d sae kindly, (loved, so)

Had we never lov’d sae blindly!

Never met – or never parted –

We had ne’er been broken-hearted. (would never have been)

“These lines,” wrote Sir Walter Scott, “hold the essence of a thousand love-stories.”

Reading this work, tinged with such deep sadness, I think again of the comment of Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) – 16th President of the USA – that the aspect of Robert Burns’ genius he most admired was the poet’s ability fully to grasp and encompass his subject, leaving nothing more to be said. A remarkable talent.

Clarinda’s final words to Burns expressed the hope that they might meet again in Heaven.

Music

The poet’s first teacher, John Murdoch (1747-C.1824), recalling his small class at Alloway, thought that ‘Robert’s ear, in particular, was remarkably dull’ – meaning that the little boy appeared to have no sense of music – a statement which I find puzzling. Murdoch, although able, was himself young and of short experience; I suspect that wee Robert – his star pupil, and grave and serious by nature – was simply too shy to sing in the presence of the others. No, Robert Burns clearly had a keen appreciation of music, and especially of melodies. It’s well known that he played some sort of pipe, and could easily coax a tune out of his fiddle (violin).

The song collections

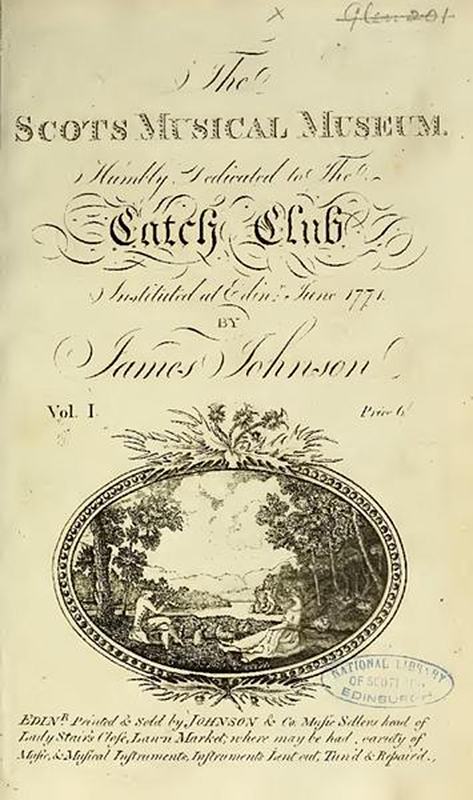

It was while the Edinburgh poems were being prepared for the press that William Smellie introduced Burns to James Johnson (1750-1811), a fellow printer and a music publisher, whose workshop was then in Bell’s Wynd. It is difficult to overstate the importance of their meeting in February 1787, for it was to have a huge influence in shaping the remaining years of the poet’s short life. Johnson was well established in business, having devised a more efficient method of printing sheet music by the use of etched zinc plates. As it happens, he had a passion for traditional Scots songs, and was concerned that some were being lost or forgotten by simple neglect. Burns was enthused to learn that Johnson had already conceived of an ambitious project to collect and publish just as many of these old songs as possible, thus preserving them for posterity. The poet readily offered to help in any way that he could, and entirely without payment.

The Scots Musical Museum by James Johnson Vol.I

Johnson had named his work The Scots Musical Museum. In total six volumes came out in the 16 years 1787-1803, each containing 100 songs, so Burns did not survive to see the fulfilment of Johnson’s plan. At the time of their meeting, Volume 1 was almost ready to go to press, so Robert’s contribution to it was small. But Burns’ enthusiasm was such that he soon became, in effect, editor of the whole project, a task that he continued until his death in July 1796. (I confess that I know little of Stephen Clarke, 1735-1797, the organist in Edinburgh who was musical editor of the first five volumes.) In total, Burns supplied almost 400 songs to the Scots Musical Museum, about 250 of which were either original to him, or ‘repaired’ or improved by him. That’s quite remarkable, don’t you think? We can now see that Robert Burns’ work as a song-writer and collector begins to rival his achievements in poetry! Independently of his valuable help with Johnson’s project, Burns sent over 100 songs towards a second important collection, that of the publisher and music lover George Thomson (1757-1851). Again, Robert accepted no payment, for to him the saving of these old songs, for centuries embedded in the culture of his native land, would be a work of national importance, almost a sacred duty. The six volumes of Thomson’s A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs for the Voice appeared between 1793-1841, a period of almost 50 years. Clearly, Burns’ contributions to the ‘Select Collection’ could only have been to the earliest volumes, and sent from Dumfries in the last years of his life. In contrast to Clarke’s work for Johnson’s Scots Musical Museum, George Thomson commissioned for some of the songs in his ‘Select Collection’ elaborate settings by such giants as Haydn and Beethoven. (Oddly, there seems to be no evidence that Burns and Thomson ever met.)

A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs for the Voice Burns

Ellisland, 1788-1791

.

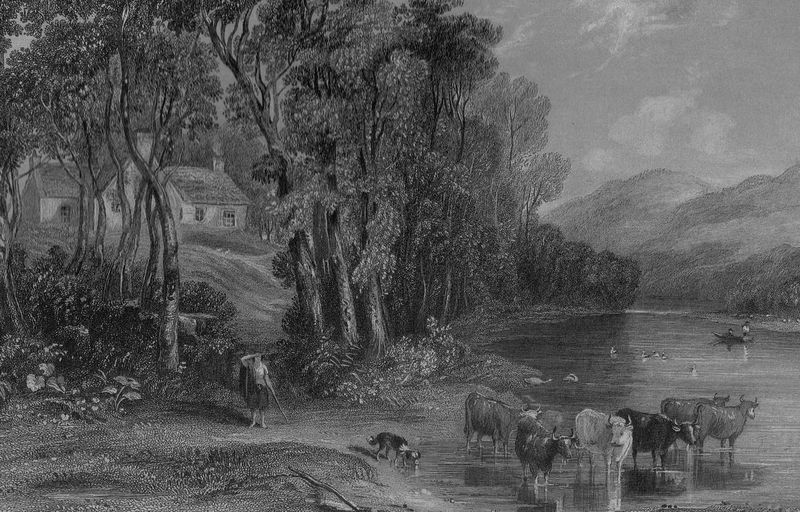

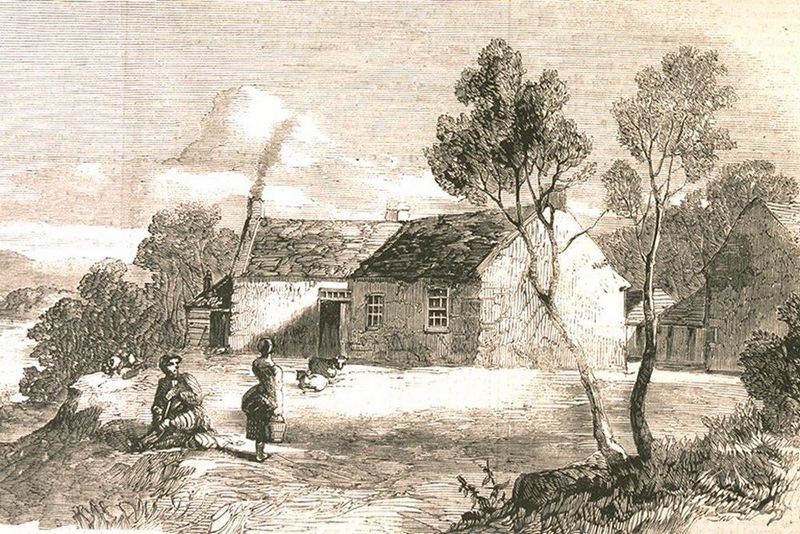

Ellisland Farm in the time of Robert Burns – Source Wikimedia

Now, how did Robert Burns come to be at Ellisland at all? It’s no exaggeration to say that during his early days in Edinburgh – and probably not for the first time – the poet’s whole future was uncertain. Undeniably, his personal life was in a mess. Having some money at his disposal, he considered briefly buying a commission as an Army officer. (Yes, that was permitted.) The idea of joining the Customs and Excise also appealed to him, and would offer secure employment and a decent annual salary. Robert craved financial security, for he was now the father of several children and anxious to take responsibility for each one. He was reluctant to return to farming, with all its hardships, but a new tenancy would at least bring him a home of his own, a place where he could settle to a regular family life.

Army service may have been no more than a romantic notion, but such things are the stock-in-trade of a poet! It was soon arranged that Robert would begin a course of instruction in Customs and Excise duties, with a view to taking up a position when one became available. And Burns signed a lease governing his tenancy at Ellisland. His landlord there was to be Patrick Miller (1731-1815), a Glaswegian by birth, but a leading banker in Scotland’s capital and a very wealthy man. Eager to meet the new poet from Ayrshire that everyone was talking about, Miller invited Robert to his home in Edinburgh on 12 December 1786. In the course of what, I’m sure, would have been a most interesting conversation – for here Burns excelled – they got down to business.

.

River Nith at Ellisland Scotland

Miller would have explained that in 1785 he had purchased – unseen – the Dalswinton Estate at Auldgirth, just over five miles north of Dumfries. Separately, he had bought Ellisland farm in the following year from James Veitch of Eliock, Sanquhar. Neglected and in poor condition, Ellisland extended to about 170 acres, and lay immediately to the west of the River Nith. Miller offered to the poet a choice of the three farms that he then owned (the others being Foregirth and Bankhead), but Robert appears to have fixed his interest from the start on Ellisland. I’m tempted to think that Ellisland’s attractive situation by the river was the decisive factor, allied to the fact that, as a condition of the lease, Miller would provide a new farmhouse to accommodate the Burns family. It would be a pleasant place, too, in which to receive visitors. Burns’ plan was simply to earn what he could from this new enterprise, until he was confirmed as an officer of the Excise service

Engraving of Friars Carse circa 1800

Within a few weeks of coming to Ellisland, Burns had met the owner of Friars’ Carse, the handsome mansion house immediately to the north. Captain Robert Riddell (1755-1794), although only four years older than the poet, had retired from army service on half-pay after the victory of the American Colonists in their war of independence. Belonging to an old Dumfriesshire family, Riddell was a cultured man who had been educated at the universities of Edinburgh and St Andrews. He had studied history and had a considerable knowledge of antiquities, but what may have drawn him immediately to Burns was their shared interest in music. James Mackay tells us that Riddell had some talent as a composer, and had published works of his own; he would have been fascinated to hear of Burns’ involvement in the Scots Musical Museum, a project potentially of such importance. The two young men soon became friends.

.

Friars Carse Country House Hotel Dumfries & Galloway © 2015 Scotiana

Friars’ Carse, extended since the 1700’s, now operates as a fine hotel. I’m sure you will remember our visit there, Jean-Claude and Marie-Agnes – it must have been in the summer of 2015. 🙂 Before having our meal, we went in search of the Hermitage, the little summerhouse among the trees to which Riddell had given Burns a key, knowing that he could write there undisturbed. (Historically, Friars’ Carse had belonged to the monks of Melrose Abbey. The tiny Hermitage, built of red sandstone in the ecclesiastical style, stands guard at the grave of one of the friars.)

Burns Hermitage pannel at Friars Carse Country House Hotel © 2015 Scotiana

.

Burns Hermitage at Friars Carse Hotel © 2015 Scotiana

Burns took over the lease of Ellisland on 25 May 1788. His new farmhouse would take ten or eleven months to complete, so the poet was obliged to lodge in simple accommodation nearby. It’s known that Robert helped from time to time in the construction, most of the work being done by Sandy Crombie, a skilled stone-mason. Both men happened to be present on 14 October, and would have been intrigued to hear a regular beating sound from the direction of Dalswinton Loch, perhaps just 400 metres away – it turned out that Burns’ landlord, Patrick Miller, was conducting a test of the world’s first steam-powered boat, a small craft built for him by James Taylor and William Symington (1763-1831), designer of the water-pumping engines at the Wanlockhead lead mine. (Miller conducted further tests on Dalswinton Loch with a larger vessel in December 1789, but seems to have lost interest soon afterwards in the development of steam-boats.)

Patrick Miller National Portrait Gallery London

Yet Miller is worthy of further notice, for he was involved in an astonishingly wide range of activities and concerns. Today, he would certainly be classed as a multi-millionaire. Mackay writes of him : “Patrick Miller, a director and later Deputy-Governor of the Bank of Scotland, a director of the Carron Ironworks (at Falkirk) and a prominent businessman, is best remembered for inventing the Carronade (a small but powerful naval gun) and for his experiments with paddleboats. A twin-hulled boat propelled by manually-operated paddles was sailed to Sweden under his direction in 1787. The King of Sweden then presented Miller with a sumptuous gold box containing a packet of turnip seeds. In this curious manner, ‘Swede’ turnips became one of the staples of Scottish agriculture in the late eighteenth century.” We might add that Miller was also an agricultural reformer and the pioneer of several improvements to farm machinery.

Captain Robert Riddell – Source National Library of Scotland

There is no reason to think that Burns travelled as a passenger on either of Miller’s steam-powered boats. James Mackay suggests that the poet’s relationship with his landlord was not sufficiently cordial, but that the two became better friends after Robert gave up his tenancy. How fortunate the poet was, though, to have as a neighbour such a congenial companion as Captain Riddell at Friars’ Carse who, we’re told, was good enough to share with Burns his copies of the morning newspapers.

We can only wonder that Burns had any leisure at all for reading – or writing – at this time, for Ellisland farm was in very poor condition indeed. The 170 acres included an apple orchard, but the soil itself was barren, undrained and full of stones. Robert struggled with it as best he could for a year and a half, before declaring in a letter to Gilbert (January 1790) that the farm had proved ‘a ruinous affair’. Regarding the stones, it was as though God had deposited at Ellisland ‘the very riddlings of Creation’!

Song-writing and collecting at Ellisland

Fortunately, the poet was soon firmly established in his new career with the Customs and Excise. In September 1789 he took up full-time employment, covering 10 parishes in Upper Nithsdale that stretched to the Ayrshire border. This was tiring work, for it entailed riding up to 40 miles daily, five times a week, and a working day of 14 hours. Burns put this time spent in the saddle to good use, however, often musing on a new poetic creation or fitting words to a familiar tune as he rode along.

It was certainly helpful to Robert, as far as the gathering and recording of songs was concerned, to meet so many people in the course of his new job. (Excise duties were levied in the 1700’s on a wide range of goods, not only on alcohol, and were often seen as falling disproportionately on the poor, and thus unfair.) Prof Gerry Carruthers of the University of Glasgow has estimated that Burns contributed to Johnson’s Scots Musical Museum about 135 songs, or one-third of his total, during the time he spent at Ellisland. (Prof Carruthers has been Secretary of the Robert Burns Ellisland Trust since April 2020.)

.

Jean Armour statue in Dumfries Scotland © 2012 Scotiana

For some years now, it had been Burns’ practice, when writing to Mrs Dunlop – his ‘Mother Confessor’ in Ayrshire, and a lady whose opinions he valued – to enclose a copy of his latest poem or song, thus giving us the approximate date of its composition. One or two of Robert’s best-known songs, inspired by scenes to the north in Ayrshire, probably date from 1788, his first year at Ellisland, although I cannot be sure. I’m thinking of Ye Banks and Braes o’ Bonnie Doon and Of A’ the Airts the Wind Can Blaw, a particularly tender and beautiful song, inspired by Jean Armour (1756-1834), whom Burns had left behind at Mauchline, and who was destined to be – at last – his wife.

Of A’ the Airts the Wind Can Blaw

Of a’ the airts the wind can blaw, I dearly lo’e the west, (of all the directions the wind can blow; lo’e = love)

For there the bonnie lassie lives, the lassie I lo’e best .. (the pretty girl I love best)

The powers abune can only ken, to whom this heart is seen, (only the Powers above can know, who see the poet’s heart)

That nane can be sae dear to me, as my sweet, lovely Jean! (no other can be so dear to me)

Kenneth McKellar (1927-2010), Scotland’s finest tenor of modern times, interprets this Burns song beautifully.

Auld Lang Syne

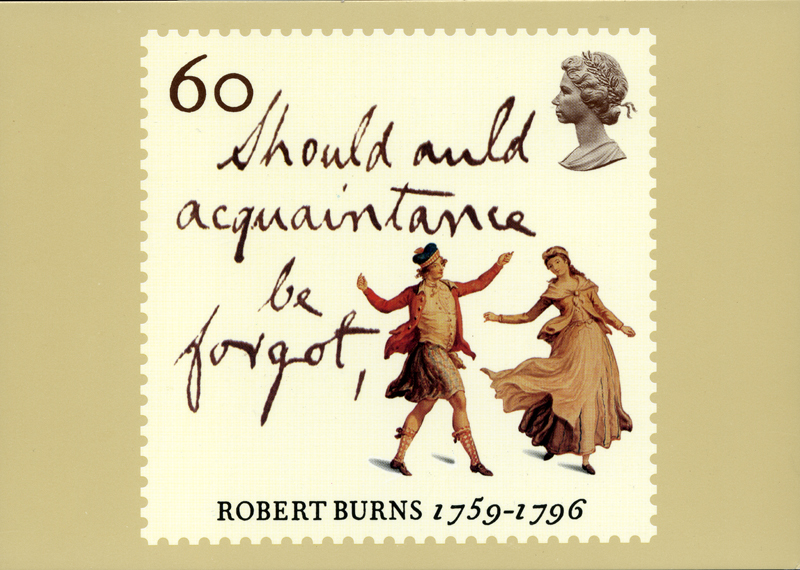

It was in the last days of 1788 that Burns wrote again to Mrs Dunlop from Ellisland, enclosing his much-improved words for the traditional song Auld Lang Syne. The words remain difficult, yet this song of friendship has become the second most-frequently sung of any in the world! A pentatonic scale is used, common to Eastern music and the music of the highland bagpipe.

Should auld acquaintance be forgot, and never brought to mind? (an old friendship be forgotten, never recalled)

Should auld acquaintance be forgot, and days of auld lang syne? (and the days of long ago)

The days of ‘auld lang syne’, I have translated as ‘the days of long ago’ – the poet’s meaning is that long-established friendships are the most precious, hallowed by the passing of the years.

Robert’s letter of 17 December began : ‘Is not the Scotch phrase Auld Lang Syne exceedingly expressive? There is an old song and tune that has often thrilled through my soul .. .. You know I am an enthusiast in old Scotch songs ..’

Later, he would write : ‘Old Scots songs are, you know, a favourite study and pursuit of mine .. .. There is a certain something in the old Scots songs, a wild happiness of thought and expression ..’

Afton Water

New Cumnock Robert Burns sign

New Cumnock Robert Burns mural Afton Water © 2015 Scotiana

A letter of 5 February 1789 suggests that Afton Water had been written at Ellisland around that date. This song, again with a strong Ayrshire connection, has for me the most enchanting melody of any composed by Burns, and a gently-rippling rhythm. All of its words are English. I probably have in my collection half-a-dozen recordings by such singers as Joseph Hislop (1884 -1977), Sydney MacEwan (1908-1991), Peter Mallan (1934-2014) and Moira Anderson (b.1938), but Kenneth McKellar’s would be my favourite :

‘My Mary’s asleep by thy murmuring stream; Flow gently, sweet Afton, disturb not her dream.’

The subscription library

In March 1789, Burns and Riddell of Friars’ Carse founded together a small subscription library at Monkland Cottage, in the village we now call Dunscore. Members paid five shillings on joining, and sixpence each month thereafter. (I understand that this little enterprise continued to operate until the 1930’s, and that some of its books found their way to Ellisland.)

On Seeing a Wounded Hare limp by me

It was soon after writing Afton Water that Robert composed this short poem, again entirely in English, ‘On Seeing a Wounded Hare limp by me, which a Fellow had just shot at’. The incident which inspired it occurred at an early hour on 19 April, as Burns made clear when he wrote once more to his friend and adviser, Mrs Dunlop : “While sowing in the fields, I heard a shot and presently a poor little hare limped by me, apparently very much hurt .. .. this set my humanity in tears and my indignation in arms ..” The hare was, in fact, a female, about to give birth, and targeted out of season. Burns was furious with the fellow concerned, and felt like throwing him into the river, something he was well able to do! But the poet’s sympathy for the poor, suffering animal was overwhelming, as he imagined it creeping off to die in some lonely place.

‘Go live, poor wanderer of the wood and field, The bitter little that of life remains ..’

The new farmhouse is ready

Burns’Farm At Ellisland on the River Nith near Dumfries

What excitement there must have been on this day, so eagerly anticipated, when the poet and his small family entered their new home! (We know only that it was towards the end of April 1789.) A young servant girl led the little procession, carrying before her, as was traditional, a Bible and a dish of salt. The Ellisland farmhouse was single-storey and thatched with heather, its five apartments arranged in the shape of a letter T. It had a well-equipped kitchen, with one of the first Carron domestic ovens to be installed, in addition to the more usual cast-iron cooking range (also from the famous ironworks at Falkirk – Scotland’s industrial revolution had begun.) In the attics above, the indoor and outdoor servants would sleep.

A Victorian version of Robert Burns with Jean Armour 1878

Burns had now formalised his marriage to Jean Armour (1756-1834), daughter of a prominent stonemason at Mauchline, and a woman whose forbearance and generosity in the face of his many infidelities was nothing short of heroic. Jean understood above all, I think, the unique value and importance of the poet’s work, and was a wonderful help to him. She deserves also to be remembered.

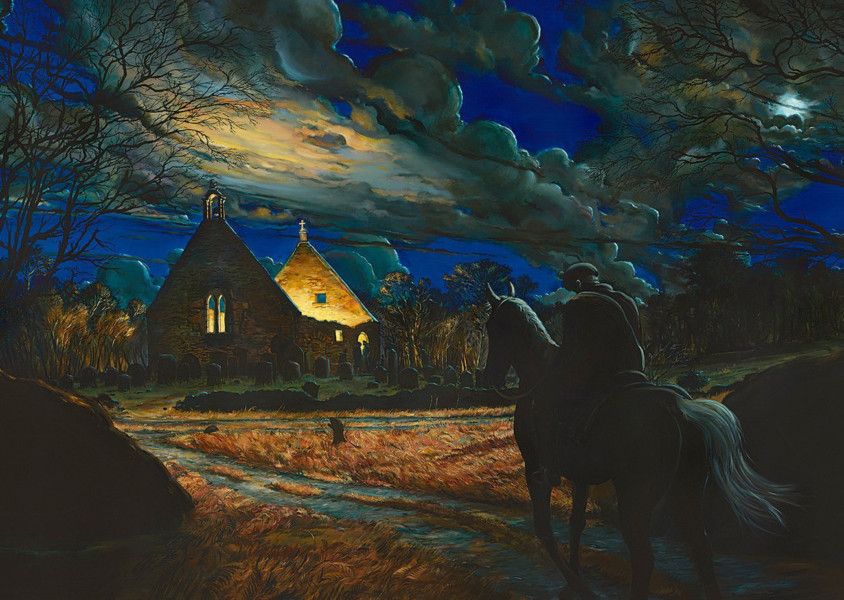

Tam o’ Shanter, a Tale

Burns produced some of his finest work at Ellisland. In first place, almost certainly, would be the long tale in verse, Tam o’ Shanter, that Robert himself considered his masterpiece. The story of how these 220 famous lines came to be composed and committed to paper is very interesting – and, once again, Capt Robert Riddell has an important part to play. For a matter of weeks, Riddell had entertained at Friars’ Carse a friend who was also a retired soldier (and fellow Captain), but an older man of almost 60 years of age. This was Francis Grose (1731-1791), who was English but of Swiss ancestry, and a fascinating individual. Burns met Capt Grose several times, and declared that he had never come across a man ‘of more original observation, anecdote or remark’. Chers Amis, we can only imagine the sparkling exchanges between the poet, such a brilliant conversationalist, and this rotund, jovial man with his inexhaustible fund of stories! The two got on ‘like a house on fire’.

Captain Francis Grose (1731-1791) Antiquary and Friend of Robert Burns

Francis Grose shared Riddell’s passion for history and antiquities, and had embarked on a project to publish a series of gazetteers (atlases) of the surviving ruins and antiquities to be found throughout Britain and Ireland. Six volumes on England and Wales had already come out, and in 1789 the first of two volumes appeared that he planned to compile on the antiquities of Scotland. The purpose of Grose’s long tour in the south-west was therefore to make sketches and gather the information he would need to complete his second Scottish book. In conversation with Burns, probably in June 1789, the subject of the ruined and long-abandoned Auld Kirk at Alloway came up. This was a place dear to the poet’s heart, as we know, for here lay the dust of his departed father, the ‘tender father and the generous friend’. It had the reputation, too, of being haunted.

Alloway Auld Kirk © 2012 Scotiana

Gilbert Burns assures us that Capt Grose and the poet struck a sort of informal bargain – that if Grose undertook to include Auld Kirk Alloway in his book, Burns would write a tale of witchcraft to accompany the engraving of the old church. Only by December 1790, however, was the splendid long poem completed, having probably been set down on paper over a period of a month or so in whatever leisure moments Robert could find. Burns must have been exceptionally busy – let’s not forget that he still had a farm to supervise (although it had now become principally a dairy farm, run by Jean and the servants) and since July 1790 his Excise work had been based in Dumfries, keeping him away from Ellisland all day. Tam o’ Shanter appeared, as promised, in Volume II of the ‘Antiquities of Scotland’ in April 1791. (Sadly, Francis Grose died in Ireland in the following month. He was very obese and did not enjoy good health.)

The small village of Kirkoswald, 12 miles or so south of Ayr – and the childhood home of Burns’ mother, Agnes Brown (1732-1820) – has a direct connection to the Tam o’ Shanter poem, for Tam himself was inspired by a Kirkoswald man, Douglas Graham (1739-1811) of Shanter farm, who allegedly had a weakness for alcohol. In Robert’s tale, Tam goes to the inn after the Ayr market has closed – as was his habit – drinking all evening with his old friend from the village, Souter Johnnie (John Davidson the shoemaker, 1728-1806). The two sit comfortably by the fire, while a fierce storm rages outside. Eventually their money is all spent, and Tam rides home as fast as he can, approaching at a late hour the haunted Auld Kirk of Alloway.

Alloway Poet’s Path Old Nick playing pipes © 2012 Scotiana

Hearing music from within, he creeps up to have a look and sees the Devil himself ‘in the form of a beast’ playing the bagpipes, while witches and warlocks dance all around! Tam is fascinated by their leader, who has the appearance of a pretty young woman. She wears a very short dress and dances wildly. Although half-drunk, poor Tam’s excitement increases and he cannot resist calling out: ‘Weel done, Cutty-Sark!’ – ‘Well done, Girl in the short dress!’ In an instant all becomes dark and the devilish crew set off after him – he has been caught spying. A furious chase then follows. Just two yards ahead of his pursuers, Tam narrowly manages to escape at the Auld Brig o’ Doon (the old bridge across the River Doon) because witches – as is well known! – cannot cross running water. Poor Maggie, his pony, is not so lucky though, for her tail is pulled off …

Burns declares this long poem to be a warning to men everywhere against the dangers of strong drink and pretty girls in short dresses. His tone is not entirely serious, of course. The young poet writes ‘with his tongue in his cheek’, but leaves us with a splendidly amusing piece of work.

Alloway Poet’s Path witches purchasing Tam © 2012 Scotiana

Last days at Ellisland

Burns’ promotion to the Dumfries Third Division of the Excise in July 1790 brought with it an increase in salary, to £70 per year. The poet’s work was now done within the town itself, so Pegasus, his pony, was used only for commuting purposes. Regarding the farm, we read that after largely abandoning the growing of crops, Burns introduced the new Ayrshire breed of dairy cattle, of which he had a small herd of 10 or so. He and Jean must often have felt desperate to be rid of the farm altogether, and simply did the best they could to earn some kind of return. But they were trapped by the contract that Burns had signed with Patrick Miller, which still had years to run.

We tend to think of the life of Robert Burns as being one of disappointments, ill-health and hardships, and so can only imagine the joy at Ellisland when word arrived that a neighbour, John Morrin of Laggan, had agreed to buy the farm from Miller, thus releasing Burns from his obligation. By 11 November 1791 all stock and equipment had been sold off, and Robert and Jean moved out.

.

Robert Burns mural outside Burns’ s House Dumfries © 2012 Scotiana

.

Dumfries, 1791-1796

Robert Burns Statue – Dumfries © 2004 Scotiana

The Burns family’s first home in Dumfries was a rather cramped flat above the Stamp Office in what is now Bank Street. The location was not ideal, for an open sewer close by carried filthy water into the River Nith at the Whitesands. The Distributor of Stamps, John Syme (1755-1831), was therefore a neighbour. He was a splendid man, trained in the law and destined to become the most loyal and sterling friend Burns ever had. After the poet’s death, Syme worked tirelessly to help and protect Jean and the children.

Maria Riddell, portrait c.1806 by Thomas Lawrence

Marie-Agnes, Jean-Claude, Janice, I think I ought also to mention the name of Mrs Maria Riddell (1772-1808) – although little space remains – for Burns’ friendship with this beautiful and high-born young lady was the most intriguing of his Dumfries years. Maria was English by birth, and when not quite 18 had become the second wife of Walter Riddell (1764-1802), younger brother of Capt Robert Riddell of Friars’ Carse. Most importantly, though, Maria was intellectually gifted, a spirited and independently- minded woman and a lover of literature and poetry. Although Burns was some 13 years older, she and the poet were soul-mates – and Burns, predictably, was captivated and ‘more than half in love with her’ (James Mackay). Following an estrangement of a year or so, they were happily reconciled. Maria placed laurels on Burns’ fresh grave and paid the first public tribute to him in the obituary notice she composed for the Dumfries Journal.

At Dumfries, Robert threw himself more energetically than ever into the business of composing, repairing and collecting Scots songs, and we know that for several periods of months on end this activity was nothing short of frenetic.

Prise de la Bastille (1789) Jean-Pierre Houël

Chers Amis, as you might imagine, Burns had taken a close interest in events in France since the start of the Revolution, when the old Bastille prison was attacked by a furious Parisian mob. Burns’ political views became increasingly radical, but as a government employee he had to be careful to keep his opinions to himself. Even to be caught in possession of such books as The Rights of Man by Thomas Paine (1737-1809) would have led, at the very least, to his dismissal from the Excise service. Such was the tyranny under which Scotland then lived.

Thomas Muir of Hunters Hill by David Martin 1790

It was while travelling in Galloway in August 1793 with his good friend John Syme, that Burns received a further grim warning not to raise his voice in political matters. (Maybe this was fortunate, for Robert tended by nature to be outspoken.) At Gatehouse-of- Fleet, Burns and Syme witnessed one of the earliest Scottish political reformers, Thomas Muir of Huntershill (Glasgow), being led in shackles and under guard to stand trial in Edinburgh for ‘sedition’. Muir (1765-1799), a lawyer and the son of a minor laird, was sentenced to 14 years’ transportation to Australia. (He escaped, but never saw Scotland again. After many all-but-incredible adventures, he died at Chantilly, Paris, where in his last days he had lived almost secretly. The postman identified him.)

About this time, Burns composed ‘Scots Wha Hae wi’ Wallace bled’ – Scots, Who Have bled with Wallace (in the fight for independence). Not being directly critical of the government of that day, Robert may have judged it safe to publish. For many Scots, however, this powerful song remains their preferred national anthem.

William Wallace stained glass window – Wallace Monument Stirling © 2019 Scotiana

In January 1795 Burns sent to George Thomson his great hymn to the brotherhood of man, ‘A Man’s a Man for a’ that’ (in spite of everything / come what may). Writing with passion and deep feeling in his robust and vigorous native Scots, Burns asserts the worth of the common man, honest but born to poverty, as so many were. (Poverty is not good, but neither is it in itself a moral failing!) The poem builds to a climax as Robert broadens his horizon to encompass all of humankind. These lines, more than any others from his pen, have endeared Burns to the whole world, their power enhanced by the utter simplicity of language :

For a’ that, an a’ that (in spite of everything, come what may)

It’s comin’ yet for a’ that, (coming)

That man to man, the world o’er (all over the world)

Shall brithers be for a’ that. (brothers)

Dr James Mackay has calculated that Burns sent in all 57 letters to George Thomson (the music-publisher whom he never actually met), generally enclosing each time a new or repaired song. To Mrs Frances Dunlop in Ayrshire, his most frequent correspondent, the poet had sent no fewer than 77 letters during the years of their friendship. (Mrs Dunlop was godmother to at least one of Robert’s children.) But Frances Dunlop discontinued her correspondence with Burns, giving little warning and no explanation.

The difficulty arose from the serious situation in France – as the events of the Revolution became ever more bloody, there was genuine fear among the land-owning classes in Britain that violent disorder might break out here, too. With each month that passed, Burns seemed to become increasing radical in his views, which unsettled and offended Mrs Dunlop. Finally, he had expressed satisfaction that Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, the French king and queen, had both been guillotined! Burns had gone too far. A last letter from his hand, as he lay dying, received no reply, although Mrs Dunlop is thought to have made some enquiries regarding the poet from Gilbert.

Chers Amis, how blessed we are to have modern medical science (although it can still face unexpected and terrible challenges as we have discovered during the Covid-19 pandemic.) It was all so different in Burns’ day, 60 years before our first understanding of bacteria, antiseptics or anaesthesia. Robert’s heart was damaged at Mount Oliphant, almost certainly causing a lasting impairment. In adulthood, he appears to have suffered from some sort of depressive illness, and of course he met with all the usual accidents incidental to horse- riding and the heavy manual work to which he had been no stranger. Beginning around May 1795, Burns suffered increasingly from pain and weakness that his doctor was unable to relieve, and which had a cumulative effect. (Our best estimate today is that he had fallen victim to bacterial endocarditis, treatable with antibiotics.)

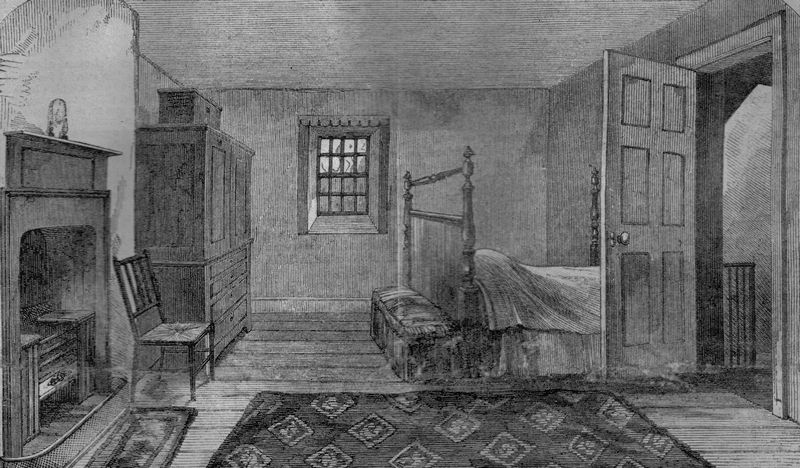

The death room of Robert Burns – Source Wikipedia

Robert’s life was ebbing away. Pale and ghastly, his friends could no longer recognise him. Finally – desperately – Burns’ young friend, Dr William Maxwell (1760-1834) prescribed sea-bathing – prolonged immersion in the cold waters of the Solway at Ruthwell, which probably did more harm than good. No cure resulted, and poor Burns was obliged to take to his bed. Weak as he was, his mind was alert to the end, which came on 21 July 1796. “We cannot but be moved and inspired,” writes James Mackay, “by the nobility of this man who was still composing songs of matchless beauty, sung and enjoyed to this day, within days of his death.”

With the last vestiges of his strength, Burns committed to paper a tender and lovely song inspired by Jessie Lewars (1778-1855), the kindly girl who had been helping to care for him. (Jean was heavily pregnant and would give birth in a few days.) Jessie, just 17, was the daughter of John Lewars, Robert’s colleague in the Excise and his close neighbour at Bank Street. I wonder if the poet heard Jessie sing as his soul departed this world, for she had a sweet voice?

‘O, wert thou in the cauld blast On yonder lea, on yonder lea,

My plaidie to the angry airt, I’d shelter thee, I’d shelter thee ..’

(I translate very freely!) In the cruel wind, I would shelter you;

Should Misfortune strike you, My breast will shield and comfort you;

The desert would be a Paradise, if you were there (for I love you) ..

St Michael’s Church Dumfries © 2012 Scotiana

Being a member of the Dumfries Volunteers, Burns was accorded a military funeral. Hundreds lined the streets, as to the Dead March from Handel’s ‘Saul’, the procession covered the short distance between St Michael’s Churchyard and the red sandstone house (in Burns Street) where the young poet died. He had lived on the edge of poverty, but enriched Scotland and the world beyond measure.

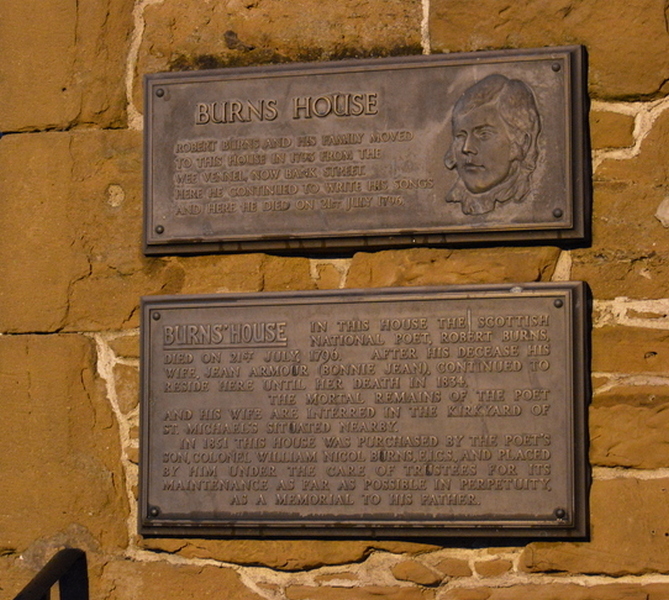

Burns’ house in Dumfries © 2012 Scotiana

Commemorative plaques on Burns’ House in Dumfries (1793-1796) © 2012 Scotiana

Ellisland today

Marie-Agnes, Jean-Claude, Janice, the story of how the original Ellisland Trust came to be established is not well known now (and the detail may be rather complicated), but my understanding is that the farm where Burns did so much of his best writing was bought in the very early 1920’s by a wealthy Edinburgh businessman and admirer of the poet, Mr George Williamson, with a view to protecting the property and securing its future. However, Mr Williamson died quite soon afterwards, on 29 September 1922. His brother, John Wilson Williamson, may have inherited Ellisland, but in any case by 1928 or 1929 the Trust was formally established.

The farm and home of our National Poet was now the property of the people of Scotland, and was opened to visitors free of charge. As I recall, the rules stipulated however that there should be, for example, ‘no picnics, and no charabancs’. The terms of the Trust provided also that the holders of certain positions of authority in Dumfries would, by virtue of their office, automatically become eligible to join the Board of Trustees. Thus, such people as the Sheriff, the Chief Constable and senior local government officials – invariably men at that time – administered the affairs of Ellisland, and so great was then the level of interest in Robert Burns generally that this arrangement worked well for many years. (Interestingly, Burns House in Millbrae Vennel, now Burns Street, where the poet died, was restored and opened as a museum and place of pilgrimage only in 1935.)

Dr Samuel Marshak (1187-1964)

Dr Samuel Marshak (1887-1964), the academic and eminent translator of the works of Burns into Russian, must be one of the most significant visitors ever to come to Ellisland. Dr Marshak had studied for a time in London, but it was only in 1959 that he realised his long-held ambition to make a tour of the places most closely associated with the poet. (I did once see a photo of the Russian scholar, pictured beside the ‘Poet’s Path’ by the Nith at Ellisland. The bi-centenary of Burns’ birth was commemorated, of course, in 1959 and a number of the events were televised.) Samuel Marshak’s first translations from Burns had come out in 1924 and others followed, selling a million copies altogether in 30 years. Robert’s ideal of Universal Brotherhood was well received in many countries, but found a particular resonance, as is well known, with the socialist government of the former Soviet Union.

I well remember, as a boy, buying the two Russian ‘Burns’ postage stamps available in 1959, and sadly have seen for myself the decline of interest in Robert Burns and his work that has taken place since that date – a slow and gradual decline, admittedly, but a continuous one. Who can say when it first began, or for that matter estimate the date at which popular interest in Burns was at its height? I would guess that the growing popularity of Hollywood films in the 1930’s and 40’s probably represented a turning point, followed by the coming of TV.

[This video isn’t available anymore — youtu.be/-CXkczzzrsI ]

Kenneth McKellar starred throughout the 1960’s in two Christmas pantomimes at the Alhambra theatre, Glasgow, each loosely based on the life-story of our National Poet. ‘A Wish for Jamie’ and ‘A Love for Jamie’ in turn gave McKellar an opportunity to sing many of Burns’ most beautiful songs. We occupied the cheaper seats in one of the ‘circles’, but could have heard a fly clearing its throat down in the stalls as Kenneth prepared to give us ‘My Love is Like a Red, Red Rose’. Times were changing, though – the Alhambra was demolished soon afterwards to make way for a huge office block, and audiences began to prefer the ‘sing-along’ style to hearing classically-trained virtuoso singers!

At school, Burns’ poems were essential for the Ordinary Grade English exam (at about age 15). I remember clearly that we studied ‘Mary Morison’ and ‘John Anderson, My Jo’ – a moving poem on love that lasts a lifetime – as well as ‘The Cotter’s Saturday Night’ and, of course, ‘Tam o’ Shanter’. Betty Davidson I still recall as the superstitious old woman who helped Burns’ mother at the Alloway cottage, firing wee Robert’s imagination with her tales and songs of devils, ghosts, fairies, brownies, witches, warlocks, spunkies, kelpies, wraiths, apparitions and giants – or have I missed one or two? To me, it seems crazy that most pupils learn so little of Burns today. Even the youngest would love to be able to address his ‘wee, sleekit, cow’ring, tim’rous beastie’ – just to say the words! – a home-grown alternative to the more usual dinosaurs and caterpillars. And the seniors’ Curriculum for Excellence would gain by having a place set aside for some study of the poems and songs of Robert Burns.

A wee story to end – perhaps best filed under Tales Out of School! (Danny Kane, the most badly behaved boy in Miss Taylor’s English class, has disrupted her lesson again.) “Hey, Miss,” he is alleged to have called out, “hey Miss, see if Robert Burns’ family were so poor, how come they could afford a hoose (house) in Alloway?’

Alloway has become a very attractive part of Ayr, and homes are expensive. The important Burns properties remain at its heart, and are all now in the care of NTS – the National Trust for Scotland. Adjacent to the old clay Cottage where the poet was born is the recently rebuilt Birthplace Museum. The Monument of 1823, in the style of a Greek temple and also recently restored, together with Alloway Auld Kirk and the preserved Brig o’ Doon, complete the group – more than enough for a full day’s tour, I would think! Janice, Marie-Agnes, Jean-Claude, you have already published a post on Alloway at Scotiana, haven’t you? You’re much more up-to-date than I am! 🙂

Auld Alloway Kirk painting for Oran Mor Glasgow by Nichol Wheatley – Source Scotsman

Alloway Burns Monument and Memorial Gardens © 2012 Scotiana

A visit to Alloway In Memoriam of Robert Burns…

We mustn’t make the mistake that young Danny did, of judging Burns by the values of today. No, Burns was light-years ahead of his time in the cruel 18th century, and fortunate indeed not to have shared the fate of Thomas Muir of Huntershill. If Robert had lived a few more years, can we be certain that he would not have suffered the same harsh punishment for his radical and strongly-held opinions – opinions that he had such trouble in keeping to himself? Let’s forget and forgive the frailties of the genius poet, continuing to honour his courage and to treasure his priceless works. Oh – and in gratitude to the Williamson brothers who saved Ellisland, let’s keep in touch with the Farm and Museum via the Trust’s excellent website. Here’s the link, giving all the latest news and further information on how best to help!

Ellisland Farm – Home, as built by Robert Burns

Á Bientôt Jean-Claude, Marie-Agnès et Janice!

Iain.

For members of Burns clubs – and those in the Burns World generally – the date of 21 July is as well-remembered as the poet’s birthday on 25 January. This year, 21 July will see the 225th Anniversary of the death of our National Poet.

Wreath-laying ceremonies will take place at many of the monuments to Burns, while at the Brow Well (near the village of Ruthwell on the Solway) it has been usual to hold a short religious service, close to the spot where the dying poet came to bathe in the sea.

Iain.

I’d like to correct two errors. Although remarkably little is known of her early life, it is now generally accepted that Burns’ wife, Jean Armour, was born on 25 February 1765, so that she was younger than the poet by six years and one month. (As a rule, Burns’ romantic affairs were with younger girls.) Jean, dark-haired and with a fine singing voice, survived as a widow at Dumfries for 38 years.

Observant readers will have noticed that Jean’s true dates (1765-1834) are inscribed on the plinth of her statue at Burns Street, Dumfries. If memory serves, the late Mr Peter J Westwood was prominent in having Jean Armour commemorated in this way. Mr Westwood also wrote a short account of her life (“Jean Armour, Mrs Robert Burns – An Illustrated Biography”) issued in 1996 in a private edition of 1,000 copies.

When writing in January, I was unaware that the final line of Burns’ tribute to his father at Auld Kirk Alloway is in fact a quotation from the Anglo-Irish poet Oliver Goldsmith (1728-1774). (Burns acknowledges this in a footnote to the lines as they appear in his Kilmarnock Edition.)

Goldsmith writes of the Preacher in his long poem, The Deserted Village :

“Thus, to relieve the wretched was his pride,

And even his failings leaned to Virtue’s side.”

The memorial stone itself is not original, souvenir-hunters having done much damage in the course of the years. But I find the inscription remarkable, for the letters, although small, have been finely and deeply cut with great skill. Your excellent photo from 2012, Jean-Claude, clearly shows the little quotation marks at each end of Goldsmith’s line. Merci bien !

Iain.

Our regular readers probably know that the others in Scotiana’s team – Marie-Agnes, Jean-Claude and Janice – have kindly helped us for more than 10 years now to publish these Letters from Scotland, whether by drawing maps, etc. or by finding so many splendid photos and illustrations.

I was astonished to find that this Letter on Robert Burns runs to slightly over 10,000 words – but the poet has a special place in the hearts of most Scots, and I was anxious to trace at least an outline of his whole life here on earth.

For a short time I wondered whether this post would appear before 25 January, for I had carelessly attempted to send off the very long text through the Email system. In the event, all of it arrived as ‘raw data’, but only 40% or so as originally composed!

Somehow, mysteriously, Dear Friends, you succeeded in recovering all of the lost text, with complete accuracy. Marie-Agnes and Jean-Claude, I suspect that the help of your son Jean-Christophe – an IT professional – may have been decisive; Margaret and I look forward to thanking him in person.

“Chers Amis, je vous remercie de tout coeur” – from the bottom of my heart, Dear Friends, I thank you all for your kindness and for the small ‘miracle’ that you have performed! 🙂

Iain.

Quite soon it will again be the season to enjoy one of those friendly, convivial evening events, the Burns Supper!

Those of us who learnt of Burns and his poetry at school rarely forget, I think. We remember both the life of the poet and his outlook on the world, his mode of thought.

Over 20 years ago, travelling near Ruthwell on the Solway with some others, I witnessed an interesting small event. It was springtime and the wild birds were repairing and building their nests. As our private bus approached, a blackbird – carrying a twig in its beak and flying awkwardly – crashed into the windscreen and was sadly killed.

I thought, of course, of Robert Burns, and of the memorable lines in which, full of sympathy, he would have recorded this small tragedy!

Iain.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-south-scotland-60082608

Dr William Napier, an architectural historian, has reported that a remarkable number of the buildings at Ellisland date from Burns’ time there. With the place so little changed, the poet would have no trouble at all in recognising it.

Visitors are pleased to see that Ellisland remains an active farm. Bertie Austin and his family have worked the lands there for over 40 years.

It has often been remarked that, of all the properties connected with Burns, the poet’s presence can most readily be imagined at Ellisland. I can understand this feeling – and especially when one is down by the River Nith and beyond the sight and sound of motor cars.

Iain.

The 2022 Annual General Meeting and Conference of the Robert Burns World Federation (RBWF) will take place at the Cairndale Hotel, Dumfries, from 9-11 September. Among other trips, delegates from the USA, Canada, Australia and all parts of the UK will visit Ellisland Farm and the Annandale Distillery (established in 1836 and reborn in 2014 after major investment). Following church on the Sunday morning, a wreath-laying ceremony will be held at the Burns Mausoleum in St Michael’s Churchyard.

Iain.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-64153615

It’s thought that only 84 copies of Burns’ original Kilmarnock Edition poems survive today, of the 612 that were published in 1786 in simple, pale-blue paper covers. I’d guess that most of these surviving copies were later given more substantial bindings.

Facsimile reprints of the Kilmarnock Edition have appeared over the years – the one that I have is from 1927. It’s by John Smith & Son of Glasgow and has 240 pages, approx. 235x153mm. Burns’ Preface of three-and-a-half pages ends with these words :

“(The Author) begs his readers, particularly the Learned and the Polite, who may honour him with a perusal, that they will make every allowance for Education and Circumstances of Life; but if, after a fair, candid and impartial criticism, he shall stand convicted of Dullness and Nonsense .. let him be condemned, without mercy, to contempt and oblivion.”

Burns need not have been concerned. His poems sold out in a matter of weeks.

Iain.

Two new books may now be seen at Burns House, Dumfries, the house where the poet died. These are copies of Creech’s Second Edinburgh Edition, ‘Considerably Enlarged’ of Burns’ poems (from 1793), and were sent as a gift to the poet’s patron Robert Graham of Fintry and his wife, Margaret Elizabeth.

In his Dedication, Burns records his gratitude for the friendship of the Grahams, and hints at his own mortality as he ends with the words : ‘This page may be read when the hand that now writes it, is mouldering in the dust.’

Burns House may be visited free of charge. It’s generally open from Tuesday until Saturday each week, 10.00-13.00 and 14.00-17.00. For further details see : http://www.dgculture.co.uk

Iain.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-south-scotland-64371857

Just in time for the poet’s birthday celebrations on 25 January, the BBC have brought news of the discovery of some new and original Burns material at Barnbougle Castle (a large tower house close to Cramond and Queensferry on the River Forth, belonging to the Rosebery family). Enclosed in a huge folder labelled ‘Burnsiana’ are various papers and documents, many relating directly to Burns’ time at Ellisland Farm. They record such things as the cost of materials to build the house, and give details of Jean’s spending each week on food and domestic items.

It’s thought that these records were collected by Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery (1847-1929), an admirer of Burns (and, as a politician, British Prime Minister from 1894-1895).

Iain.

https://www.dgwgo.com/dumfries-galloway-news/plan-save-birthplace-auld-lang-syne/?mc_cid=7b77c9268b&mc_eid=cff9ce0f3e

Ambitious plans to secure the long-term future of Ellisland Farm were unveiled on 27 February, and I wish them all success. Among other developments, a new free-standing Visitor Centre is proposed, situated several hundred metres from the original farmhouse. It will have a Cafe, Exhibition Space and Toilets, etc. I do hope that (as at Abbotsford) the Visitor Centre will be a welcoming place with free admission, so that even those who hadn’t realised they were interested in Robert Burns will call in as they pass on the busy A76.

https://www.ellislandfarm.co.uk/stay/

The Robert Burns Ellisland Trust completed on 7 July a small but high-quality self-catering holiday cottage, situated just a few yards from the poet’s original old farmhouse.

Constructed in the mid-20thC as accommodation for a farm worker, Auld Acquaintance Cottage has been virtually rebuilt, renovated internally to the highest modern standards. All decoration and furnishing was undertaken by local tradespeople. Externally, the cottage was refashioned so as to blend sympathetically with the older surrounding buildings.

For 18 years – until 2021 – Auld Acquaintance Cottage had been the home of Mrs Pat Saunders. She was very happy in this idyllic spot and spent her 90th birthday at Ellisland. On fine days she would walk by the river, in the chance of again catching a glimpse of the kingfisher!

Iain.

Among the Notable Dates listed in my diary is the birthday of Robert Burns on 25 January. But even the birthday of William Shakespeare – held by Google to be the greatest writer in English – is not mentioned. (Its date is thought to be around 23 April 1564, St.George’s Day.)

“For years,” wrote Burns’ slightly younger brother Gilbert (1760-1827), “butcher’s meat was a stranger in our house.” Money was always short. Oatmeal, now recognised as a ‘wonder food,’ had long been an essential part of the Scots peasant diet, whether eaten as porridge or combined with onion and tasty mutton scraps to make ‘haggis’. (I’m pretty sure that this word is derived from the French ‘hachis’. Certainly, all of the ingredients are finely chopped up.)

I would encourage anyone who has never tasted haggis to give it a try, for a well-made haggis can be surprisingly good to eat. (It’s possible now to buy haggis in a tin, and simply to heat it for a few minutes in a microwave oven.)

Iain.

https://www.dgwgo.com/out-and-about-in-dg/burns-mausoleum-open-public/

In one of the earliest tributes to our poet, Burns’ earthly remains were reburied (1815) in the handsome Mausoleum that stands in a corner of St Michael’s Kirkyard, Dumfries. The heavy iron doors of the Mausoleum are now generally locked, although it is possible to peep inside – but Burns’ legacy is a living thing, and a new initiative this summer will once again allow visitors to enter the burial chamber, as I expect they were able to do in more ‘civilised’ times.

From April-September 2024, between Monday and Saturday each week, members of staff from nearby Burns House (in Burns Street) will attend at 11.15 and 14.15, and will be pleased to meet interested visitors. It should be possible, I think, to take photos. (The contact number for Burns House is 01387 255 297.)

Iain.

https://www.nts.org.uk/collections/robert-burns-collection

Today – 15 April 2024 – a splendid new resource became available to everyone with an interest in Robert Burns, for over 2,500 items in the Burns Collection of the National Trust for Scotland (NTS) may now be seen – and carefully studied – online.

Iain.