|

|

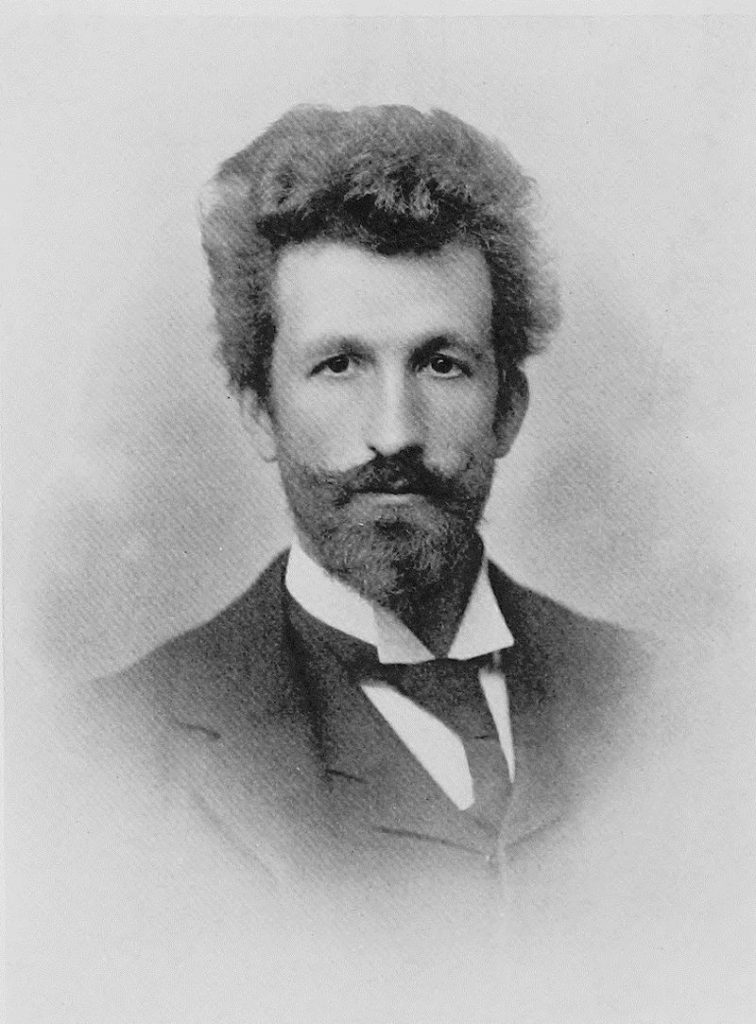

Who was ‘Don Roberto’? Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham of Gartmore, 1852-1936 ..

Cunninghame Graham (1852-1936) .

“Writer, traveller and adventurer, and with a Spanish grandmother,

I nevertheless find Cunninghame Graham’s involvement in politics

to have been the most remarkable feature of his life –

for he was from a noble Scottish family,

yet became the first ever Socialist member of our British parliament

when he entered the House of Commons in 1886.”

Bonjour Janice, Marie-Agnes et Jean-Claude – Hello again from Scotland! 🙂

.

Margaret and I hope very much that you, and all your loved ones, will continue to keep well as the terrible Covid-19 pandemic spreads around the world. The USA has been very badly affected. But today, as I write, our BBC have reported a seventh night of rioting in the United States, provoked by the killing on 25 May by the police of George Perry Floyd, an unarmed African American.

.

The disturbances that have broken out in more than 150 cities across the US, have been described by commentators as the most serious since the assassination in 1968 of the civil rights campaigner, Dr Martin Luther King (b.1929). Could it be considered in any way controversial if I were to write that the roots of inter-racial conflict in America can be traced all the way back to the slavery of the 18thC? The situation is grave indeed, when our trusted British broadcaster is able to describe the richest country on earth as ‘tearing itself apart’.

.

I confess that I have little optimism, but can only hope that the future will bring to the USA fresh opportunities to begin to heal these old and deep wounds. We are in the realm now of politics, a place of apparently never-ending struggle and debate, but one that would be familiar territory to the subject of this ‘Letter from Scotland’, Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham of Gartmore (1852-1936).

A Victorian figure in many ways – note the early year of his birth – Graham’s long life allowed him to glimpse something of our modern world. Writer, traveller and adventurer, and with a Spanish grandmother, I nevertheless find Cunninghame Graham’s involvement in politics to have been the most remarkable feature of his life – for he was from a noble Scottish family, yet became the first ever Socialist member of our British parliament when he entered the House of Commons in 1886.

.

The harsh truth is that even the lower house of parliament was then a rich man’s club, and destined to remain so until 1911 when MP’s first received a salary. Graham had no allies in the Commons, yet remained undaunted and spoke out courageously, making it clear from the start that he had no time for the petty rules and conventions of the House. As was customary, however, Cunninghame Graham’s first speech was heard without interruption. Dear friends, I think we can all imagine the shock at his powerful language as he attacked British society of the 1880’s. I quote a little from A F Tschiffely’s biography:

.

” .. .. the society in which one man works and another enjoys the fruit – the society in which capital and luxury make Heaven for thirty thousand and a Hell for thirty million, that society .. .. with its misery, its want and destitution, its degradation, its prostitution and its glaring social inequalities – the society we call London .. .. “

Before the bewildered Members had finished staring at each other, Graham strode out, leapt on his mustang Pampa and cantered towards his London home to attend to his many new duties.”

.

.

The Old House of Commons – Wikipedia

.

Cunninghame Graham sat in the House of Commons for a period of just six years, but never lost his interest in politics. He was tireless in his journalism and letter-writing, ‘campaigning’ he might have called it, striving constantly to arouse the conscience of those in power on a whole range of social and humanitarian issues. Already Graham had called for the nationalisation of major industries, votes for all adults, greater freedom of speech and an eight-hour working day – to which he soon added demands for prison reform, an end to hanging and flogging, rights in law for illegitimate children, and the protection of ponies working in the coal mines. It’s no exaggeration, I think, to say that these proposed reforms were three generations ahead of their time, for most were indeed to be realised, although it took over 60 years!

.

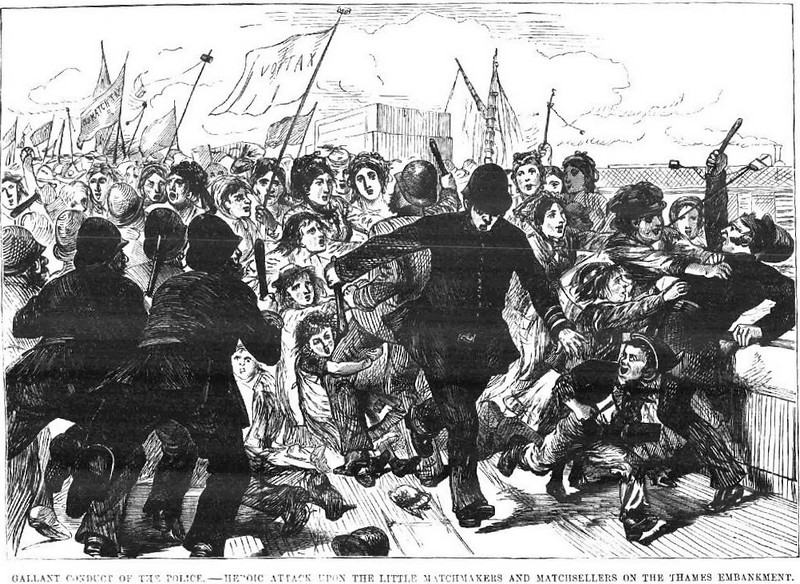

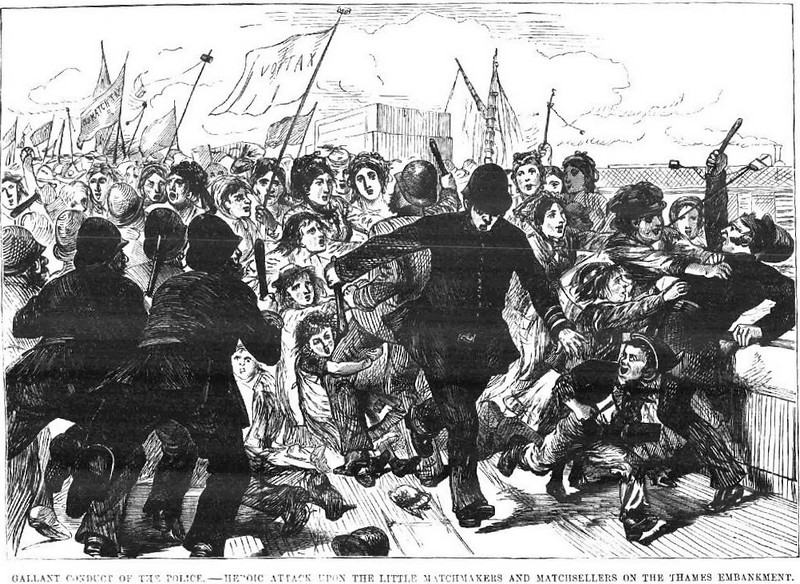

The_Days_Doings_-_Saturday_6_May_1871

Many of the early Socialists took the view that trade union activity – the organising of labour, and calling of strikes if necessary – would more quickly bring improvement to the lives of the poor than would fine words uttered in parliament. Robert Cunninghame Graham could see the truth in this, and while he sat in the Commons took a prominent role in supporting both the ‘Match Girls’ Strike’ of July 1888 and the London Dockers’ Strike that began in August 1889. In both disputes the workers achieved their demands. The strike at Bryant & May’s match factory had begun over dangerous and unfair working conditions, as well as low pay. In the case of the London dock workers, a pay increase of 20% was won for most of the 100,000 men, together with better security of employment, but only after a bitter five-week strike that might well have failed without the support of fellow dock workers in far-off Australia.

1887 Bloody Sunday London

.

These were hard times indeed for the most poorly paid. The risk of civil disorder in London had been increasing so much that public demonstrations were forbidden in the capital in 1887, a further provocation to the developing Socialist movement. A new battle-ground was being created, over the issues of freedom of speech and freedom of assembly, so it was no surprise that the rally in Trafalgar Square against unemployment on 13 November ended in a riot. Serious trouble had been expected as the banned marches and rally went ahead, and army units stood by to support the police. There was much violence, with more than 70 people badly injured and over 400 arrests made. Robert Cunninghame Graham and his fellow Socialist, John Burns, as leaders, were severely beaten by the police, but also arrested and taken to court. For his part in these events of ‘Bloody Sunday’, each man was sentenced to six weeks’ imprisonment.

Pentonville prison in 1842 Wikipedia

.

.

Graham was a sincere Socialist. He had the courage of his convictions, and in later life took pride in having been sent to Pentonville Prison. (I seem to recall reading that his visiting card had at one time carried a photograph from those days passed ‘at Her Majesty’s Pleasure’.)

.

Don Roberto (left) and Aimé Tschiffely riding together in London.

.

Fortunately, several full biographies of Cunninghame Graham have appeared over the years, the book by Graham’s younger friend, the Swiss-born Aime Tschiffely, possibly having achieved the largest sale when it came out in 1937. Tschiffely (1895-1954) tells how, by invitation, he began this work several years before Cunninghame Graham’s death, and how the two men would sit talking late into the night, until the candles had burnt down. Tschiffely shared the older man’s passions for horse-riding, adventures and the outdoor life, and was probably like a son – or grandson – to him, for Graham had no children of his own.

.

.

Don Roberto : Being the Account of the Life and Works of R B Cunninghame Graham, 1852-1936

Aime Felix Tschiffely, Heinemann, London, 1937.

.

Graham earned the affectionate nickname of Don Roberto during the first seven years he spent in South America, on account of both his aristocratic origins and his mastery of the Spanish language. There had in fact been an earlier biography, by the American academic Herbert Faulkner West (1898-1974). West had a long association with the prestigious Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, USA, but his book is now extremely rare and I haven’t seen it.

.

A Modern Conquistador : Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham, his Life and Works –

Herbert Faulkner West, Cranley & Day, London, 1932.

.

It was from a later ‘life’ that I learnt why young Robert Cunninghame Graham had left Harrow School (in North London) after just two years, and soon made his way to Argentina in the hope of making his fortune in cattle-ranching – a plan destined not to be successful. Despite the family’s apparent wealth from three Scottish estates – Finlaystone and Ardoch (on the Clyde) and Gartmore (Stirlingshire) – huge debts had also been accumulating, and, more pressingly, the courts had appointed a Curator to administer the Cunninghame Graham affairs, so that ‘ready money’ was in short supply. The sad reason for this was that Robert’s father, having suffered for years from a head injury, ended by losing his mind. Understandably, Aime Tschiffely, as a friend, saw no reason to make these family matters public. Are they really any of our business, I wonder?

.

.

.

Cunninghame Graham : A Critical Biography – Cedric Watts & Laurence Davies,

Cambridge University Press, 1979. ISBN 0521224675

.

Watts and Davies, also academics, address more fully Graham’s reputation as a writer, for he produced a wide range of work – essays, sketches, short stories – many drawing upon the astonishingly rich fund of memories he had gathered in an extraordinary life. While still a teenager (a concept unknown to Robert’s generation!) he would write home at length to his mother from Argentina, then a lawless place and one on the edge of civil war. Trying – not always successfully – to protect her from undue alarm, he nevertheless told her of his high adventures.

.

As a matter of routine, Roberto would carry a revolver, a 12 shot repeating Winchester rifle, a sword and a knife – yet some places remained unsafe, and it was wiser to travel in groups – gangs – of fifteen! A young man grows up very quickly in such circumstances, for even before he was 19 he had been press-ganged into joining a band of revolutionaries. Of slim build, but muscular and blessed with robust health, Robert developed an astonishing ability as a horseman and rider – and, most importantly, had quickly learnt to fall safely from the saddle, the skill most admired by his fellow ‘gauchos’.

.

It was in the second half of his long life that Cunninghame Graham produced the dozens of books for which he is remembered – that is, from the mid-1890’s onwards. Adventures in Morocco and Spain provided much material – ‘vintage travel’ to us today. There were pen portraits of friends, and sad, atmospheric accounts of the funerals of some of them..

.

William Morris portrait by George Frederic Watts 1870

.

such as his fellow socialists William Morris (1834-1896)

.

James Keir Hardie by John Furley Lewis,1902

.

and James Keir Hardie (1856-1915).

.

The funeral ceremony of Keir Hardie, the Scots-born first leader in parliament of the Labour Party, took place at the chapel of the Crematorium

within the huge Western Necropolis, Glasgow. Graham’s essay on his friend is included in his collection of 1916, ‘Brought Forward’ :

.

.

“I saw him, simple and yet with something of the prophet in his air, and something of the seer. .. .. He made mistakes, but then those who make no mistakes seldom make anything. His life was one long battle, so it seemed to me that it was fitting that at his funeral the north-east wind should howl amongst the trees, tossing and twisting them as he himself was twisted and storm-tossed in his tempestuous passage through the world.”

.

.

Graham’s writing was varied and ranged widely. In another piece from the same collection, he describes an event in a smart Parisian hotel, a scene of some opulence, where couples were dancing the tango. Inevitably, one young lady had caught Robert’s attention, causing him to remember her years later. (Brought Forward can be read free of charge at the Project Gutenberg website.)

.

.Critics have often found an elegaic quality in Cunninghame Graham’s work, a lamentation that this world is not a kinder, gentler, fairer place. But his keen powers of observation – and first-class memory – allowed Graham to recall small and amusing detail, which he liked to incorporate into his stories. Perhaps he was first and foremost a story-teller. His style has been compared to that of Maupassant. He might recall a fellow somewhere, with a half-burnt but unlit cigarette stuck to his lip, hoping for above half an hour ‘to meet a man with a match about him’. Or, writing of the men who crewed some small boat, he would describe ‘their red and scraggy necks, that stuck out of their collars like vultures’.

.

Joseph Conrad’s Letters to Cunninghame Graham Cambridge University Press

.

As the centre of so much of Britain’s cultural life, Graham maintained a home in London even after he left parliament. Riding in Hyde Park was a favourite relaxation. Meeting literary friends was convenient too, such people as the Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) or the Polish-English novelist Joseph Conrad (1857-1924). One might think there to be a strong point of comparison between the writing of Conrad and that of Graham, for both men in their youth had experienced the most extraordinary adventures. Yet Conrad did not see it that way at all. “When I think of you,” he wrote to Cunninghame Graham, “I feel as though I have lived all my life in a dark hole, without seeing or knowing anything.” Now, that’s a memorable quotation, don’t you think?

.

.Robert Cunninghame Graham was the eldest of three brothers, but Charles (1854-1917) and Malise (1860-1885) both predeceased him. Graham’s heir at his death in 1936 – according to the Scottish law on land inheritance – was therefore his nephew Angus, son of his brotherCharles. Angus achieved distinction as a courtier and as an Admiral in the Royal Navy. Jean, daughter of Admiral Sir Angus Cunninghame Graham (1893-1981), who became on her second marriage Lady Polwarth, also published a biography of her famous great-uncle.

.

Gaucho Laird : The Life of R B ‘Don Roberto’ Cunninghame Graham (Softcover) –

Jean Cunninghame Graham (Lady Polwarth), Long Riders’ Guild Press, 2005. ISBN 9781590481790

.

Lady Polwarth died only in 2018. Her book, which I haven’t seen, has been said by reviewers to be particularly strong on the earlier years of Don Roberto’s life. Also published in 2005 was a further biography of this distinguished Scot, a very full work of 352 pages, which I understand takes particular notice of his political activities:

.

The People’s Laird : A Life of Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham –

Anne Taylor, The Tobias Press, 2005. ISBN 9780954963507 (Softcover)

.

Anne Taylor’s is the book which I would recommend, I think, if I were to buy just one, but as the years pass these older biographies become more difficult to find – a great pity, for the remarkable and fascinating life of Cunninghame Graham ought to be better known and his name more widely recognised.

.

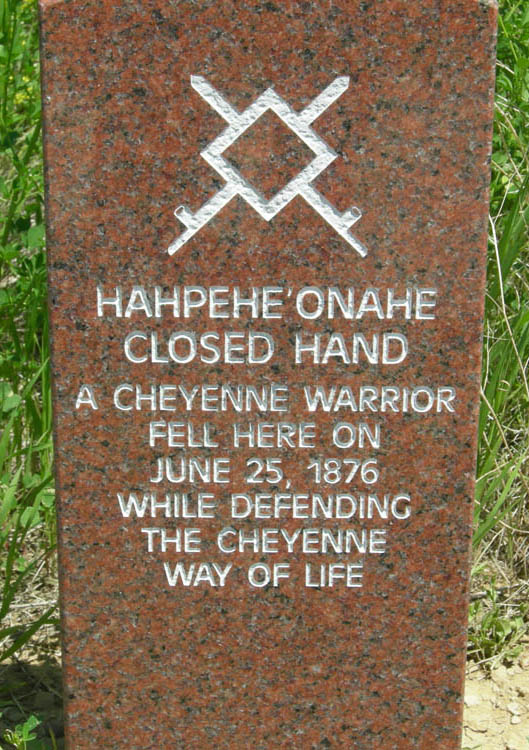

Little-bighorn-memorial-sculpture-2

.

It seems to me, dear friends, that Graham’s lifelong concern with politics and what we might call ‘world affairs’ was driven by forces deep within his character. Unusually perhaps, his first instinct was to identify with others, especially where they were perceived to be suffering injustice, for he was above all a humanitarian. At the height of colonial expansion, he was one of the few to speak out against imperialism and the exploitation of native peoples. He correctly identified and condemned the genocide of the American Plains Indians.

.

.

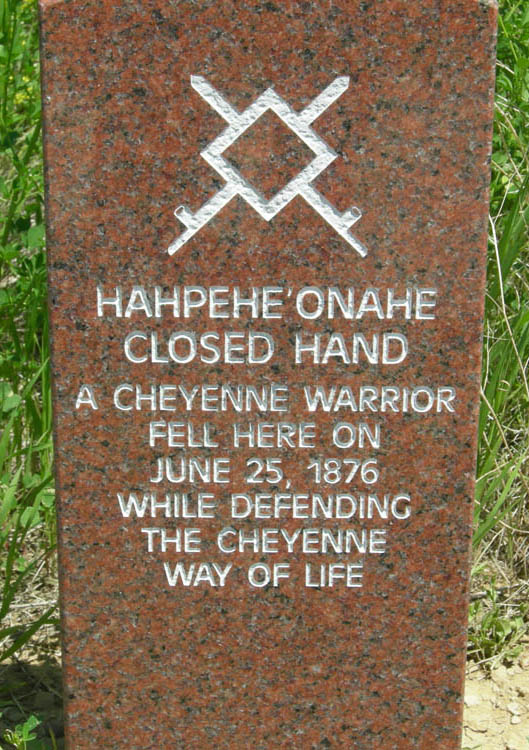

Marker stone on the Cheyenne territory

.

Throughout his life Graham continued to travel, his ‘international’ outlook confirmed. In later years, he confided to Tschiffely that he felt his habits of thought to be more Spanish than Scottish. As for the practice of politics, much of that he compared to ‘the ploughing of sand’. I suspect that this remark simply betrayed Cunninghame Graham’s disappointment at the slow rate of progress that had been achieved towards building a fairer society. In this harsh world, was he too much of an idealist? As a writer though, his influence might well have been more long-lasting and ultimately greater than he could have foreseen.

.

Tracing his descent from the ancient kings of the Scots, Robert Cunninghame Graham was very much interested in the ‘national’ question. He did not see self-government for Scotland as being opposed in any way to internationalism, but rather as its natural starting-point. Nor was he anti-English in the least; he criticised instead those of his fellow Scots who did not share his ambition for the future of their country.

.

Jean-Claude, Janice, Marie-Agnes, were you able to find that old photograph I mentioned, from 1928? (I understand that it’s now in the public domain.) Pictured in the group are those who spoke at the first public meeting of the new National Party of Scotland, held at the St Andrew’s Halls, Glasgow. At the invitation of John MacCormick (1904-1961), on whose initiative the party had been founded in April 1928, Cunninghame Graham served as President.

.

.

The first meeting of the National Pary of Scotland in 1828

.

.

From left to right, the speakers were:

- The Duke of Montrose (1878-1954), 6th Duke and Chief of Clan Graham;

- Compton Mackenzie (1883-1972), novelist and historian;

- R B Cunninghame Graham (1852-1936);

- Hugh MacDiarmid (1892-1978), poet and writer;

- James Valentine (1906-2007), doctor of medicine,

- and John MacCormick himself, the Glasgow lawyer and passionate nationalist.

.

It’s fair to say, I think, that the National Party were a left-of-centre group. By 1932 they faced a more right-wing rival, the Scottish Party, but largely due to the personal influence of MacCormick, the two were brought together in 1934 to form the Scottish National Party of today. Again, Robert Cunninghame Graham was chosen as the new party’s first President. Having witnessed in the House of Commons of the 1880’s Ireland’s bitter struggle for self-government, he was under no illusion that Scottish ‘home rule’ would be achieved quickly. (In the event, it took 65 years, for our current Scottish Parliament was not established until 12 May 1999. Even now, certain powers are reserved to London.)

.

Bannockburn battlefield Memorial in Stirling © 2020 Scotiana

.

By 1934 Graham had attained the age of 82 years, but apart from occasional rheumatism he seems to have kept well. He continued to ride, leading on horseback several of the rallies in the 1930’s to the field of Bannockburn (Stirling), the scene of Bruce’s defeat of the English invaders on 23 and 24 June 1314.

.

Portrait of Gabriela Cunninghame Graham by Frederick Hollyer

.

Robert Cunninghame Graham spent the last 30 years of his life as a widower, for his wife, whom the world knew as Gabriela, had died in 1906 when only in her mid-40’s. They were said to have met in Paris and were married, almost secretly, in 1878, at the Strand registry office, London. Tschiffely described Gabriela as dark-haired and very pretty, with soft grey-blue eyes. It was a case of ‘love at first sight’, he wrote. She could not have been more than 20 years old, and was said to be of Spanish and French descent.

.

Only in 1985 did it become known that Gabriela had in fact been English-born, the second daughter of Dr Henry Horsfall, a surgeon of Masham, N. Yorkshire. It’s not for me to speculate on what might have brought her alone to Paris, where she would clearly have been insome danger. Enough, I think, that the young people delighted in each other and were happy together. Roberto agreed on this point:

.

“It is a natural desire in the majority of men to keep a Secret Garden in their souls, a something

they do not care to talk about – still less to set down, for the other members of the herd to trample on.”

.

The couple were most free to travel together during the first five years of their marriage, for the death of Robert’s father in 1883 brought him much extra responsibility, and his membership of the House of Commons would in time require his full attention. Gabriela’s and Robert’s business ventures in Texas and Mexico were not successful and they returned to Scotland little better off, but with a new family pet, Jack, the wire-haired terrier whom they had adopted. An account of these adventures was included in Gabriela’s book of short stories The Christ of Toro, published in 1908, two years after her death. Highly intelligent and studious, yet imaginative and creative, Gabriela was gifted in so many ways. I seem to recall reading that Roberto felt most in love with her when they were deep in conversation.

.

.

.

Whereas Graham would not have described himself as religious, Gabriela had been attracted to Catholicism. According to several biographers, her position was that of a ‘Catholic mystic’, although I confess that I’m not sure of all that this term implies. Gabriela wrote poetry that has been highly regarded, but her most important work is the definitive two-volume biography of the Spanish Saint Teresa of Avila (1515-1582), which came out in 1894. (Santa Teresa: Being Some Account of Her Life and Times. As a tribute from Robert, a second edition appeared in 1907. Rhymes from a World Unknown, a collection of Gabriela’s poetry, was privately printed the following year.)

.

.The mistress of the Gartmore and Ardoch estates had become passionately interested in the life and work of Teresa, the Carmelite nun of noble birth who was so influential in reorganising her Order at the time of the Counter-Reformation. Generally accompanied only by her faithful maid Peregrina, Gabriela would travel tirelessly through Spain in the footsteps of the Saint, stopping where she had stopped, sleeping where she was known to have rested. Sadly, it was on the return from one such long trip that Gabriela became seriously ill at the village of Hendaye, in the south of France, where she was obliged to leave the train. Robert rushed to her side, but she could not be saved. (Diabetes was present in Gabriela’s family, and this disease may have been the cause of her death.)

.

Aerial view of Inchmahome Priory, Inchmahome Island, Lake of Menteith Wikimedia

.

As was her wish, Gabriela was laid to rest within the walls of the ruined Augustinian priory on the island of Inchmahome in the Lake of Menteith, a place that she loved and to which she had often come to pray.

.

Don Roberto on Pampa by Sir John Lavery

.

Lest we should become too sad, dear friends, I’d like now to attempt to trace the career of Pampa, Don Roberto’s favourite horse and one of the joys of his life – while not forgetting that all life must one day come to an end. I can’t be sure of the date, but it’s almost certainly between the years 1883-1886 that our story begins (that is, during the time between Robert becoming ‘laird’ and his election to parliament.)

.

Walking through the streets of Glasgow one day, his attention was caught by a horse, hitched to a tramway car, that seemed unused to the work and was giving the driver a great deal of trouble. Approaching to help – for few understood horses better – Roberto recognised the animal as an Argentine mustang, and on looking more closely discovered that it bore the brand of Eduardo Casey of Curumulan, a ranch he remembered from his young days in Argentina!

.

An example of British horse-drawn tram circa 1890

.

So delighted was Graham by this happy surprise that he resolved immediately to go and see the director of the tramway company. (This would probably have been Mr Andrew Menzies of the Glasgow Tramway & Omnibus Company of 1872-1894.) Aime Tschiffely continues the story: “When Don Roberto heard that the horse had only arrived from South America two days before, and that it was one of the most troublesome the company had ever tried to handle, he offered 50 pounds for it. As this was about three times the sum the company had paid, the deal was made at once. When the tramcar came back, having completed a journey, Don Roberto himself unharnessed the animal, put a saddle on him, and after a wild tussle in which the mustang came out second-best, rode him to Gartmore. ‘Pampa’, as he called the horse, turned out to be the best and highest-spirited he ever possessed .. ”

.

.

Gartmore House Stirling – Jonathan on Wikipedia

.

I don’t have Pampa’s complete life-story, of course, but I’ve read that when – in 1900 – the Cunninghame Grahams had to give up their beloved Gartmore estate, he was moved down to London, where he was stabled just outside the city. (At the summer fetes held each year in the grounds of Gartmore House, the village children had often enjoyed rides on Talla, Gabriela’s Icelandic pony.) Early-morning rides with Pampa in Hyde Park, Kensington, were a favourite relaxation for Robert.

.

The years passed, inevitably, and the decision was taken to retire Pampa from service, to ‘put him out to grass’. On a small farm at Weybridge, Surrey, he had the company of two other horses, and for a while lived happily. But he suffered a kick to the knee; the wound failed to heal properly and became infected. To spare his old friend unnecessary pain, Robert reluctantly agreed that he should be put to sleep. It was now 1911, and Pampa had attained the splendid age of 31 years. He was interred on the farm.

.

The Horses of the Conquest R.B. Cunninghame Graham cover illustration

.

.

Cunninghame Graham confessed to friends how much he grieved for his beloved Pampa. Margaret and I know, Marie-Agnes and Jean-Claude, that you will understand the pain he suffered, for you have often spoken to us of dear Ralfou 😉 , your German Shepherd dog who died a long time ago. Neither did Cunninghame Graham forget, for it was 19 years later that his book The Horses of the Conquest began:

.

To Pampa,

My black Argentine – whom I rode for twenty years, without a fall.

May the earth lie on him as lightly as he once trod upon its face.

Vale . . . or until so long.

.

.

The Horses of the Conquest R.B. Cunninghame Graham 1949

.

I understand that the words of this Dedication appear also on the memorial to Cunninghame Graham, now located at Gartmore – and that one of the hooves of the faithful Pampa lies under the stones.

.

Cunninghame Graham Memorial in Gartmore – Wikipedia

.

.

It was probably while mounted on his ‘little horse’, El Charja, successor to Pampa, that Graham came to the rescue of a fellow equestrian – a lady – in Hyde Park. This was Mrs Elizabeth Dummett, a widow of about Robert’s own age, whose horse had become frightened and bolted. Cunninghame Graham brought Mrs Dummett back to her home in his car, and enquired kindly after her on the following day. From 1915, ‘Toppie’, as she was to become known, was a close friend and a frequent companion on Robert’s journeys. Watts and Davies continue the story:

.

“Elizabeth Dummett .. .. came of a wealthy family of Yverdun, the Mievilles. A widow when Graham met her,she was confidently affluent and a bright conversationalist. At luncheons and on Sundays her house – at 17Walton Street, near Harrod’s – held a salon attended by such writers as Axel Munthe, Compton Mackenzie and A J Cronin; other guests were Conrad, Max Beerbohm, H G Wells, John Lavery and Segovia.

Lady Brooke, Graham’s niece, used to accompany Graham and Toppie on journeys abroad; sometimes therole of chaperone was taken by Toppie’s sister, Louisa Mieville. Both sisters were with Graham when he died in Buenos Aires; and within a few years, Toppie herself was dead: her French doctor said that she had lost her will to live.”

.

Cunninghame Graham’s last journey to Argentina was a sad affair, for his strength had gone and he knew that he was dying. Aime Tschiffely was among the group who saw him depart from Paddington Station on 18 January 1936.

.

“I sensed that this would be the last time that I would see his flowing shock of silvery-white hair, and that I would never again shake his strong and friendly hand. When the train picked up speed and I could no longer follow it, my friend .. shouted a last ‘A Dios!’ to me.”

.

Robert Cunninghame Graham died in Buenos Aires on 20 March 1936. His body lay in state at the Casa del Teatro in a handsome mahogany casket, a gift from the Government of Argentina. The President of the Republic was among the many who paid their respects. “Thus Argentina bade farewell to one of the greatest friends she ever had, an ambassador of the heart,” wrote Tschiffely.

.

Inchmahome priory Lake of Menteith Stirling © 2007 Scotiana

On 18 April this distinguished Scot was laid to rest beside his ancestors and beside Gabriela, among the Spanish chestnut trees on Inchmahome.

.

Inchmahome priory where Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham and his wife Gabriela are buried © 2007 Scotiana

.

He had been determined to return once more to Argentina, the land he loved and where he had come of age, and to breathe again the air of those unending grasslands, the pampas, where all was spacious:

.

“Earth, sky, the waving continent of grass, the enormous herds of cattle and of horses, the strange effects of light, the fierce and blinding storms – and above all, the feeling in men’s minds of freedom, and of being face-to-face with nature under these Southern skies.”

.

Inchmahome ruined priory – Lake Menteith © 2007 Scotiana

|

|

What a great story and beautifully written too.

Many thanks.

Angus Tulloch

Brillant to find out more about the life and work of Don Roberto.

Of course this should be publicised as wide as possible.

Thank you, Angus and Alec, for your generous comments. They are very much appreciated!

Although I or Margaret (or occasionally both of us) compose the texts of these Letters from Scotland, we’re very happy to acknowledge the splendid help of the others in Scotiana’s team – and especially in finding so many excellent photos and illustrations.

Whether each is worth a thousand words I cannot say, but they do enliven a dull printed page! I have often wondered, could Scotiana be one of the most colourful sites on the internet?

Iain.

thank you very much.Did Lady Annie Brassey know him? HEr husband Tom in the House. Lady Annie loved riding in Argentina.

Thank you for visiting Scotiana, Deborah.

How can the name of such a man as Thomas Brassey (1805-1870) be so little known today? (I suspect that the neglect of history has much to do with it!) By background a surveyor and civil engineer, Brassey was one of the most outstanding entrepreneurs of Victorian times, and became fabulously rich. Although he seemed determined not to learn French (his wife translated), he was responsible for building 75% of the railways in France and 5% of railways throughout the world. Among his many other projects, he proposed a tunnel under the English Channel.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Brassey

The Thomas Brassey you mention, a son of the railway builder, was distinguished in politics. Enobled and wealthy, he and his wife Lady Annie could afford to travel the world in supreme luxury. Lady Annie’s book relating their adventures was remarkably successful. I have not come across any evidence, however, that she and Don Roberto ever met.

Iain.

Thank you for such a well put together page on Don Roberto. He remains far better remembered in Argentina than in either Scotland or Spain.

Your readers may be interested to know that there is a Cunninghame Graham Appreciation Society which tries to promote his memory and works. They have a Facebook Page, for those wishing to know more:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/CunninghameGrahamSociety/

They currently hold bimonthly Zoom meetings (I gave the last one in June on “The Scottish Writings of Cunninghame Graham – full notes available on the Facebook page) which are currently suspended for the summer, but due to resume late September (hopefully).

Many thanks

Additional pictures and interesting facts can be found of the Gartmore Heritage Society facebook page

My mother often spoke of Don Roberto. Her Aunt Mary Carter was cook at St Anne’s House at Ascog on Bute. Her husband Tom was the gardener. My mother visited there and stayed in the gate house. The house had a beautiful fernery and the fruit and vedge garden was across the road on the edge of the beach. Don Roberto must have been friendly with the duke as my mother remembered playing with lord Reidian (sp). When her Aunts health was bad my mother was sent to care for her. When the elderly couple retired the were given a cottage in Ascog where we spent many happy holidays. It was attahed to the Ascog post office it was called Stella Matutina. When uncle Tom passed it reverted to the catholic church for retired clergy. The house was left to go derelict. The roof had been removed and there were trees growing in the entrance hall. My mother cried when she saw it. There are bungalows on the site now. I have an old postcard that shows it. My mother was born in 1907 and was innher early teens when she first went to stay.

Hello Margaret,

Thank you for sending us such an interesting Comment. I must admit that I was unaware of Don Roberto having had a holiday home on the Isle of Bute.

Isn’t Wikipedia a splendid resource? A quick search indicates that the young fellow your Mother played with must have been Rhidian Crichton-Stuart, last of the seven children of John, Fourth Marquess of Bute.

Rhidian is a name from Wales, where the Butes had extensive holdings of land. After studying at university, Lord Rhidian Crichton-Stuart (1917-1969) became an Army Officer, attaining the rank of Captain.

Iain.